You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘pagan’ tag.

Tonight we travel once again to the ancient and mysterious island of Gotland, the largest island in the Baltic Sea. Ferrebeekeeper has already visited Gotland as the (possible) land of origin of the enigmatic Goths and as a place which is absolutely covered in beautiful medieval churches, but in this post we push further back in Gotland’s mysterious past to contemplate an ancient sculpture. The Smiss stone (Smisstenen) also known as the Ormhäxan (which means snake-witch stone) is a carved picture stone shaped like a huge piece of toast which shows three zoomorphic serpent creatures entwined in a sort of triskelion pattern. Beneath the creatures, an apparently female human figure with legs spread holds aloft two writing serpents.

As you can see, the actual stone is even more amazing than the already astonishing description (I get the sense that the red paint was added by a later hand, but, alas, I am unable to find an explanation for the brightness of the color). The stone was discovered in an ancient cemetery in Smiss in the När parish. Scholars and archaeologists have dated the stone’s construction back to 400–600 AD, the late Vendel era when great migrations changed the Germanic world–but all of the experts disagree concerning the stone’s meaning and purpose.

Some historians (the reputable ones) believe the stone shows a pagan goddess or sorceress…perhaps Hyrrokkin (a snake wielding giantess) or maybe some unknown deity left out of the Eddas. Other thinkers have speculated that the stone depicts a Minoan snake goddess (although who knows how she got to Gotland from Crete), Odin making love (?), or Daniel in the lion’s den (???). I am usually good at determining how people perceive visual art, but I confess to being perplexed by these latter interpretations. The lovely knots and sinuous serpentine animals look very much like Celtic, Pictish, and Mercian designs to me–which would comfortably place the stone’s figures within the cryptic North Sea pantheon of late antiquity. Unfortunately, there is little and less which is certain about the faith and folktales of that time. We are left with a haunting beautiful sacred stone, but like so many of the most compelling statues from humanity’s history, the real meaning slips from our grasp and we are left with haunting conjecture.

As the winter solstice approaches, the deciduous trees are bare. My back yard is a desolation of fallen leaves, dead chrysanthemums, and scraggly ornamental cabbages. Yet in the winter ruins of the garden, one tree glistens with color: its shiny dark green leaves and gorgeous red berries have made it an emblem of the season since time immemorial. The tree is Ilex aquifolium, also known as the common holly (or English holly). The small trees grow in the understory of oak and beech forests of Europe and western Asia where they can grow up to 25 meters (75 feet) tall and live for half a millennium (although most specimens are much smaller and do not live so long). Hollies are famous not just for their robust good looks but also for their sharpened leaves which literally make them a pain to care for. The wood is a lovely ivory color and is fine for carving and tooling (in fact Harry Potter’s wand was made of holly wood in the popular children’s fantasy novels).

Holly was long worshiped by Celts and Vikings before its winter hardiness and blood-red berries made it emblematic for the resurrection of Christ. Yet even before there were any people in Europe the holly was a mainstay of the great laurel forests of Cenozoic Europe. The genus ilex is the sole remaining genus of the family Aquifoliaceae which were incredibly successful in the hot wet climates of the Eocene and Oligocene. The semi-tropical forests began to die out during the great dry period of the Pliocene and were almost entirely finished off by the Pleistocene Ice Ages, yet the holly survived and adapted as the other plants vanished. Today there are nearly 500 species of holly. In addition to the well-known common holly which is so very emblematic of Christmastime, there are tropical and subtropical hollies growing around the world. There are hollies which are evergreen and hollies which are deciduous. Even if they are not as common as they were when the Earth was hotter and wetter, they are one of the great success stories among flowering plants.

This post is the third installment of a series concerning the astonishing 1600 year backstory of Santa Claus (you should start here with part 1, if you want things in chronological order). At the conclusion of yesterday’s post, Saint Nicholas was a beloved saint from Greek-speaking Anatolia who was the focus of miracle stories about fighting demons, helping the poor, and raising the dead. Many lesser-known saints have similar stories (although few miracles are as impressive as the story of Saint Nicholas resurrecting the murdered boys). So how did Saint Nicholas transition from an ascetic Mediterranean wonder-worker to de-facto god of the winter solstice?

The answer involves the multi-century conversion of northern and central Europe to Christianity. In order to facilitate the widespread conversion of Germanic and Scandinavian tribes into the Christian fold, churchmen drew on preexisting traditions and customs. Many pagan deities thus became conflated with traditional saints (a cultural syncretism not dissimilar from what we wrote about in this post about Afro-Caribbean voodoo loa) and many pagan customs worked their way into Christianity. Saint Nicholas was a stern bearded figure whose feast day occurred near Yule (winter solstice). Additionally he had a history of giving gifts, punching people, and performing strange resurrection miracles. Because of these traits Saint Nicholas became identified with Wotan (or Odin), the otherworldly wandering king of Germanic gods.

At Yuletime, Wotan would hunt through the sky on his flying eight-legged horse Sleipnir. Many of Wotan’s old names and characteristics are those of a wizard-like winter king. He had a long white beard and his epithet “Jólnir” meant “Yuletime god”. He held suzerainty over tribe of magical gnomes/dwarves who acted as his smiths and crafted wonderful weapon for him. If a youth was worthy, Wotan would bring him a shiny knife or axe (which was slipped into a shoe or under the bed). If a youth was unworthy, then the hapless dullard was in for a round of physical punishment or was simply dragged away by trolls and demons. Wotan knew who was worthy and who was not because he had two black ravens “Thought” and “Memory” who traveled through the world taking note of mortal proclivities. Speaking of animal helpers, at Yuletime it was characteristic to leave apples and carrots for Sleipnir (the flying horse) just in case Wotan decided to visit.

Stepping into these big northern shoes was a heady transition for an orthodox Mediterranean saint. Additionally, northern Europe was not culturally homogenous. Saint Nicholas took on different names and characteristics in different parts of Europe. In Germany he was known variously Weihnachtsmann, Nickel, Klaus, Boozenickel, Hans Trapp, or Pelznickel. Sometimes he was served by bestial underlings like Knecht Ruprecht or Krampus. In other regions he worked alone or opposed these winter demons. In the north Sant Nick’s dwarvish smiths morphed into a tribe of elves but in Switzerland they morphed into Moors. Wotan’s ravens turned into the famous naughty/nice list.

Later, in Holland, Saint Nicholas became Sinterklaas, a magical gift-giving bishop who traveled by means of flying sled—and who kept a captured Surinamese servant to help out (you can read about the eyebrow-raising modern interpretations of Zwarte Piet in this article by my friend Jessica). For some reason Sinterklaas was thought to live in Spain during his off-season. England (with its mix of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and French culture) had its own traditions of Father Christmas—a nature god clothed in green. Children from France waited for Père Noël to bring them gifts on his magic donkey (and don’t even ask about Ded Moroz, the Slavic Frost King who travels around Russia with Snegurochka).

In other words Saint Nicholas became more interesting and diverse as he was adopted by different folklore traditions. However he also became confusing and strange to the point of unrecognizability. Yet by the 18th and 19th centuries, new trends of globalization and industrialization were sweeping Europe—and the globe. Santa was ready to put on his red suit and drive his reindeer to his toy factory. You can read up to where his story meets the present (the temporal present!) in tomorrow’s post.

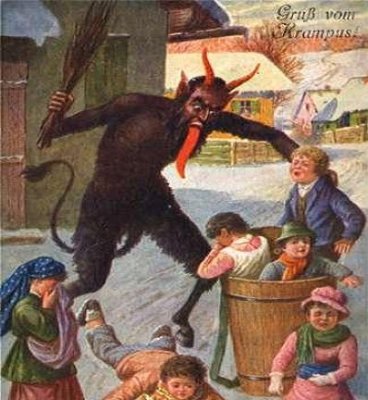

December 6th, was Krampusnacht, a holiday celebrated in Alpine regions of Germany and Austria. The festival’s roots stretch back into pre-Christian times when Germanic mountain folk paid homage to Krampus the child-stealing demon of winter darkness. Krampus was a hell-sent god with goat’s horns, coarse black fur, and a fanged maw. He would visit disobedient or inattentive children and beat them with a cruel flail before tearing them to bits with his claws (in fact “Krampus” means “claw” in old high German). The demon would then carry the dismembered bodies back to the underworld and devour the human flesh at his leisure.

December 6th, was Krampusnacht, a holiday celebrated in Alpine regions of Germany and Austria. The festival’s roots stretch back into pre-Christian times when Germanic mountain folk paid homage to Krampus the child-stealing demon of winter darkness. Krampus was a hell-sent god with goat’s horns, coarse black fur, and a fanged maw. He would visit disobedient or inattentive children and beat them with a cruel flail before tearing them to bits with his claws (in fact “Krampus” means “claw” in old high German). The demon would then carry the dismembered bodies back to the underworld and devour the human flesh at his leisure.

This harsh myth imparted crucial lessons about the cruel Alpine environment—which would literally reward inattention and carelessness with a terrible death and a vanished corpse. However there were also merry elements of year-end saturnalia to the celebration: young men dressed up as Krampus and drank and played pranks while unmarried women would dress as Frau Perchta—a nature spirit and fertility goddess who could appear as a hirsute old beast-woman or as a gorgeous scantily clad maiden. Amidst the mummery, feasts were held and presents were given. Unsurprisingly, when Christianity came to Northern Europe, these pagan celebrations were incorporated into Christmastime festivities. Thus Saint Nicholas–originally a conservative Syrian bishop (who became a protector of unfortunate children after his death) obtained a devil-like alter-ego. This wasn’t even the end of the pagan metamorphosis of Santa. The orthodox churchman also acquired a team of flying reindeer, a tribe of subservient elves, and a magical wife as Christmas traditions moved northwards into Scandinavia and combined with the universe of Norse myth!

For a time the Krampus story traveled with Santa and became part of the Christmastime traditions of German immigrants to America. Christmas cards and holiday stories often featured Krampus and his evil pagan god features were even incorporated into the popular conception of Satan. However, as Christmas became more important to merchants and tradesmen, the darker aspects of the story were toned down. Additionally fascist regimes in Germany and Austria were hostile to Krampus traditions during the thirties (and the grim imagery was not wanted after the horrors of World War II when those regimes were gone). Lately though the figure has been making a comeback in Austria and Germany and even America seems to be experiencing a renewed interest in the fiend

I am writing about this because Krampus, the clawed god of winter death, is a perfect addition to this blog’s deities of the underworld category. However, I have a more personal (and twisted) Krampus tale to tell as well. As you may know I am a toymaker who crafts chimerical animal toys and writes how-to books on toy-making. Recently a friend of mine who is an art director asked if I could build some puppets for stop-motion animation. He asked for a traditional (not-entirely jolly) Santa and for two children with no facial features–the expressions would be digitally added later.

Imagine my surprise when it turned out that the puppets were for a dark Krampus segment on a celebrity chef’s Christmas special. Anthony Bourdain, celebrity personality, adventurer, and bon vivant wanted to do an animated segment about this murderous gothic god who is still a vestigial part of the holiday. The segment was supposed to go into the nationally broadcast “No Reservations” Christmas special alongside Christopher Walken and Norah Jones, but when network executives took a closer look at Krampus, child-dismembering Alpine demon, it was decided that he should remain a vestige. So much for my showbiz career (of creating an evil Santa puppet and two faceless victims)…. The stand-alone segment can still be seen by itself on Youtube (or below). Don’t worry though, this dark holiday fable has a happy ending—I still got paid!

Happy Groundhog Day! Preliminary reports coming in seem to indicate that the nation’s most eminent groundhog oracles are not seeing their shadows today (what with the continent bestriding blizzard and all). Oddly, this is interpreted as a sign that spring will arrive early this year. However I tend to think those groundhogs on TV are media personalities who have forgotten their rural roots. When I lived on a farm, the concept behind the holiday was more straightforward: if you saw an actual groundhog on Groundhog Day, then winter might indeed end early, but if you didn’t (and I never did) winter would not be over for six more weeks. Today most non-celebrity groundhogs did not stir from their deep hibernation chambers. We probably still have plenty of winter left.

Groundhog Day is observed on or around Candelmas, which ostensibly celebrates the presentation of Baby Jesus to the temple: Mary and Joseph took Jesus to the Kohens & Levites to perform the redemption of the firstborn and ceremonially purchase their firstborn son’s life back from the priests (I’m not sure Jesus ever really escaped the priesthood or the temple of Solomon so maybe his parents should have gotten their money back–but that’s a different story). Candelmas was elided with pre-Christian holidays involving the prediction of the weather by animal augury. The holiday’s roots in America are from the Pennsylvania Germans. Apparently in pagan Germany, the original animal weather prophets were badgers or bears. Imagine how exciting this holiday would be if we stuffed our pompous civic officials together with a disgruntled bear who had just been prodded awake from hibernation so people could take flash photographs!

At any rate we have gotten rather far afield of the day’s celebrated weather oracle, the groundhog or woodchuck (Marmota monax) which is actually a rodent of the marmot family, Sciuridae. Marmots are large solitary ground squirrels which, like pikas, generally live in the mountains of Asia, Europe, and North America. The groundhog is an exception among the marmots since it prefers to live on open ground or at the edge of woodlands. The deforestation of North America for farms and subdivisions has caused groundhog population to rise. Although groundhogs are omnivores, the bulk of their diet is vegetation such as grasses, berries, and crops. They are gifted diggers who construct a deep burrow with multiple exits. This burrow serves as their chief living quarters and refuge from predators. Since groundhogs enter true hibernation, they usually also maintain a separate winter burrow (with a chamber beneath the frost line) for the sole purpose of their months-long suspended animation.

Groundhogs, however, have a deeper utility to modern humankind than as primitive weather gods. Devoted readers will know my fascination with liver research, and groundhogs are the principal research animal used in studies of Hepatitis B and liver cancer. Since groundhogs are prone to a similar virus in the wild, they always develop liver cancer when infected with hepatitis B. Laboratory groundhogs have thus been responsible for many advances in understanding liver disease and pathology–including the discovery of a vaccine for Hepatitis B and the realization that immunizing against hepatitis B virus can prevent liver cancer. Currently 350 million people around the world are suspected to have hepatitis B. Forty percent of those infected will develop chronic liver damage or cancer. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 600,000 people die every year from complications related to the infection (which is more than the total number of United States citizens killed in World War I and World War II combined). Perhaps the Groundhog should be thought of as a profound benefactor to humankind thanks to its utility as a laboratory animal.

- Melancholy (1532, Lucas Cranach, the Elder: Oil on panel. 51 x 97 cm. Copenhaguen, Statens Museum for Kunst)

Lucas Cranach the Elder painted this troubling allegorical panel of melancholia in 1532 at the end of the era of gothic painting. A shrewd but withdrawn angel sits on dark cushion and whittles a long stick into a toy for nude children who are trying to push a large globe through a hoop (the globe may or may not fit). In the middle ground, a silky white spaniel sits on the window sill above a mated pair of partridges. Is one of the birds to become the dog’s dinner?

Beyond the window, the painting’s background offers a terrible spectacle: armed opponents kill one another in a craggy Saxon landscape of walled towns and hill castles. In the skies above the battle, wild pagan deities ride the storm. Astride boars, hounds, and rams, the grim deities relentlessly pursue their hunt with casual indifference to the bloodshed below.

The painting is symbolic of the collective destiny of humankind. The angel’s mien, the animals, and the dark background all suggest that, even with heavenly assistance, the new generation will not succeed at their serious game but are condemned to a circle of violence.

Here we are at the end of tree week—an event which isn’t real anywhere but on this blog and which I didn’t even realize was happening until now. But don’t worry, I’ll be writing more about trees in the future. I really like them. Anyway, to close out this special week I’m going to write about one of my very favorite trees, the yew.

Here we are at the end of tree week—an event which isn’t real anywhere but on this blog and which I didn’t even realize was happening until now. But don’t worry, I’ll be writing more about trees in the future. I really like them. Anyway, to close out this special week I’m going to write about one of my very favorite trees, the yew.

Yews are a family (Taxaceae) of conifers. The most famous member of the family is Taxus baccata, the common yew, a tree sacred to the ancient tribal people of Britain and Ireland. Although their strange animist religion was replaced by Christianity, a cursory look at the literature and history of the English, Irish, and Scottish will reveal that the yew has remained sacred to them–albeit under other guises. The common yew is a small to medium sized conifer with flat, dark green needles. It grows naturally across Europe, North Africa, and Southwest Asia but the English have planted it everywhere they went (so pretty much everywhere on Earth). Yews are entirely poisonous except for the sweet pink berry-like aril which surrounds their bitter toxic cone. The arils are gelatinous and sweet.

Yews grow very slowly, but they don’t stop growing and they can live a very long time. This means that some specimens are ancient and huge. The Fortingall yew which grows in a churchyard in Scotland had a girth of 16 meters (or 52 feet) in 1769. According to local legend Pontius Pilate played under it when he was a boy. This is only a legend: Pilate was not in Britain during his youth. The Fortingall yew however was indeed around back in the Bronze Age long before the Romans came to England. The oldest living thing in Europe, the yew is at least 2000 years old. According to some estimates it is may be thousands of years older than that. It was killed by lackwits, souvenir hunters, and incompetent builders in the early nineteenth century…except actually it wasn’t. The tree merely went dormant for a century (!) before regrowing to its present, substantial girth. It is one of the 50 notable trees of Great Britain designated by the Exalted Tree Council of the United Kingdom to celebrate their revered monarch’s Golden Jubilee.

As noted, the people of the British Isles loved yews but they loved their horses and livestock even more and objected to having them drop dead from eating the toxic plant. This means that they planted the tree in their cemeteries and churchyards (or, indeed, built their churches around ancient sacred groves). According to pre-Christian lore, a spirit requires a bough of yew in order to find the next realm. Many English poems about death and the underworld incorporate the yew tree as a symbol, a subject, or, indeed as a character. Aristocrats also had a fondness for yew because it could be sculpted into magnificent dark green topiary for their formal gardens.

The substantial military prowess of the English during the middle ages depended on longbows made of yew. A good bow needed to be made from a stave cut from the center of the tree so that the inelastic heartwood was next to the springy outer wood. This meant that yews in England were badly overharvested and the English had to continually buy yew from Europe. To quote Wikipedia “In 1562, the Bavarian government sent a long plea to the Holy Roman Emperor asking him to stop the cutting of yew, and outlining the damage done to the forests by its selective extraction, which broke the canopy and allowed wind to destroy neighboring trees.”

Like many toxic plants, the poisonous yew has substantial medical value. The extraordinary Persian polymath Abū ‘Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn Sīnā’ (who is known in English as Avicenna) used yew to treat heart conditions in the early eleventh century—this represented the first known use of a calcium channel blocker drugs which finally came into widespread use during the 1960’s. Today chemotherapy drugs Paclitaxel and Docetaxel are manufactured from compounds taken from yews. It is believed that the yew’s fundamental cellular nature might yield clues about aging and cellular life cycles (since the yew, like the bristlecone pine, apparently does not undergo deterioration of meristem function). In other words, Yews do not grow old like other living things.

A final personal note: I naturally put a yew tree in my walled garden in Park Slope. It’s the only tree I have planted in New York. It grows very slowly but it is indifferent to drought, cold, or the large angry trees around it. It will probably be the only plant I have planted to survive if I abandon my garden.