You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘head’ tag.

Lately I have been thinking a lot about the Byzantine Empire and the long webs of connections which the Eastern Empire cast across western culture. We will talk more about this later, but, for now, let’s check out a world famous Byzantine treasure! This is the porphyry head of a Byzantine Emperor (tentatively, yet inconclusively identified as Justinian). In Venice, where the stone head has been located since the very beginning of the 13th century (as far as anyone can tell) it is known as “Carmagnola” (more about that below). Sadly, most Byzantine art objects were scattered to the four winds (or destroyed outright) when the Turks seized the city in AD 1453, however Constantinople, city of impregnable walls, had also fallen once before in AD 1203 as a part of the misbegotten Fourth Crusade (a tragicomic series of blunders and Venetian manipulation which we also need to write about). This porphyry head escaped the latter sack because it was carried off during the former!

Based on its style and construction, Carmagnola was originally manufactured by Byzantine sculptors at an unknown date sometime between the 4th and 6th centuries (AD). The diadem worn by the figure is indisputably the headdress of a late Roman Emperor who ruled a vast Mediterranean and Middle Eastern empire out of Constantinople (I guess we need to talk about the diadem of the basileus at some point too). Scholars have speculated that the original statue may have been located in the Philadelphion, a central square of old Constantinople. The figure’s nose was damaged at some point (perhaps during the iconoclasm movement or as a political statement) but has been successfully polished flat. Speaking of statue breakage, it is possible that the head goes with a large headless Byzantine trunk made of porphyry which is now located in Ravenna (although such a provenance would make it seem unlikely that the sculpture was originally located in the Philadelphion). Whatever the original location might have been, the statue was installed upon the facade of Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice (the all-important main location of Venice) after it came to the City of Canals. The head is arguably the most important object among the strange collection of cultural objects which the Venetians arranged along the Saint Mark’s facade over the centuries like an Italian grandmother putting important knickknacks on a mantle. The head’s nickname Carmagnola originates from a Venetian incident and is not some ancient Byzantine allusion: a certain infamous condottiero, Francesco Bussone da Carmagnola was beheaded on 5 May 1432 on the Piazzetta in front of Saint Mark’s after the rascally mercenary tried to trifle with the Council of Ten (who had employed him to fight his former master Duke Visconti of Milan). The red imperial head perhaps resembled the severed head of the angry squash-nosed mercenary and locals began to jestingly call it by the same name. Isn’t history funny? Anyway, in case you were trying to find it on a picture of Saint Mark’s, I have marked its location on the picture below.

It’s possible that I made a few economic missteps over the years (although, judging by the news, I am not the only one) and, as a consequence, I won’t be spending this August traveling the world. However, even if I am literally trapped in angry sweltering New York, my mind is free to roam the rugged Carpathians and take in the robust forested splendor of Romania. This land was long known as Transylvania (the “crossing forest”) and the modern world has not changed the wooded character of the land. I started to do some research online and in my virtual travels I was stunned to come upon this colossal stone head carved in the living rock of Dacia. This is a carving of Decebalus a king who ruled from 87 AD – 106 AD. Decebalus was a client king of Rome, one of the many annoying and interesting minor sovereigns whom the empire propped up around its borders to act as buffers. Much of Roman history concerns their perennial struggles with these vexatious vassals and the history of Decebalus is no different. Indeed he ended up being the last king of Dacia. His cleverness and pride went too far and Rome crushed him like a bug and absorbed Dacia.

This statue however is presumably meant to evoke Decebalus’ pride and independence (not his defeat and suicide). The head is 40 meters tall (120 feet)—it may be the largest monumental head in Europe. It was crafted by a team of 12 sculptors over 10 years at the behest of an eccentric Romanian businessman, Constantin Drăgan (1917-2008). The statue was completed in 2004 and stares balefully out over the Danube. I love Decebalus’ stony features—which seem little different from an actual rock. I am also predictably impressed at the way the natural rock looks like a crown. Dragan had some curious nationalistic misconceptions about Dacia’s place in history, and it seems this great head was meant to explain/popularize some of the millionaire’s ideas. As often happens with art, the actual work is more ambiguous and interesting…hinting at both greatness and ruin.

Ancient Egyptian mythology can seem like a baffling tangle of multi-faceted gods who subsume each others’ identities, roles, and symbols. Perhaps the best way to understand the mutable nature of Egyptian deities is to recognize that the pantheon reflected the changing political realities of Ancient Egyptian culture. The drawback with this methodology is that the culture of Ancient Egypt lasted for approximately 3000 years (!), so it is still not easy to summarize Egyptian mythology.

Consider the deity Amun Ra. Amun Ra ended up as the king of the gods of Egypt—the emperor of heaven who created all things. There were times in the New Kingdom, when worship of Amun Ra bordered on monotheism and the other gods were regarded as flickering extensions of Amun Ra. However it did not start this way. Originally Amun and Ra were separate. In the Old Kingdom Amun was a mysterious god of hidden magical breath. The Old Kingdom ended in 2181 BC in a dark age of war and strife which lasted for a century (a time now known as “the First Intermediate Period”). At the end of this period, Amun had grown in importance and become the god of the winds and the patron god of Thebes. The Middle Kingdom was a glorious age for Egyptian civilization, but it too came to an end in stagnation, civil war, and invasion—”the Second Intermediate Period”–which lasted from 1786 BC to 1550 BC. During this Second Intermediate Period, a mysterious group of heterogeneous invaders—the Hyksos—took over Egypt and created their own dynasties. The Hyksos were finally driven from Egypt by nobles from Thebes who founded the 17th dynasty (the first of the New Kingdom). Since Thebes was politically ascendant, the Theban patron god Amun merged with Ra and became ruler of the gods. Before being combined with Amun, the deity Ra had long been worshiped as the sun god.

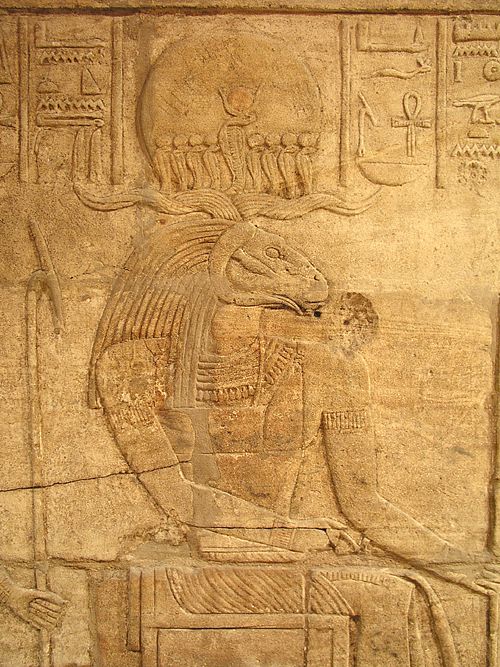

Ra traveled through the firmament on two solar boats. By day he traveled through the sky on the Mandjet (the Boat of Millions of Years). At night he took on his form as a great ram and traveled through the underworld on the Mesektet (the evening boat). Ferrebeekeeper has touched on the Mesektet before, but we were concentrating on giant evil snake deities back in those days, so ram-headed Ra didn’t really get his due in the earlier post.

Amun Ra had several forms which reflected his diverse origin, but he was most often portrayed as a mighty ram or as a pharaoh with a distinctive towering headdress…or sometimes as a falcon with the sun on his head. When I started writing this article I had hoped for some explanation of why Ra was called “Ram of the Underworld” or why the ram came to prominence over other animals to wind up as the favored animal head for the king of the gods, but if such explanations exist, they have eluded me. You’ll have to be content with the fact that the king of the gods of Egypt was most often a ram. I’m not even sure if I said that right: but I guess I don’t need to worry about literalistic ancient Egyptian priests and worshipers showing up in the comments to berate me (a consideration which crossed my mind when I decided to write about Amun Ra as opposed to other supreme sheep gods whom I could name).

Kindly forgive the last few weekdays without a post–I was on a winter solstice vacation from the internet. To cut through the holiday treacle, let’s concentrate on one of my favorite subjects—giant snake monsters! More specifically, after this year of horrible storms, I am writing about the fearsome inkanyamba, a mythical serpent-like being from South Africa. Inkanyambas are said to dwell in the pools beneath waterfalls. They have the bodies of great serpents and horselike heads. Inkanyambas are associated with powerful seasonal storms—particularly tornadoes. Such powerful local cyclones were thought to be caused by male inkanyambas out looking for mates.

The creatures are said to live in the Pietermaritzburg area of KwaZulu-Natal . The Inkanyamba is particularly associated with the 95 meter tall (310 feet) Howick Falls, South Africa. For a while the Inkanyambas of Howick Falls even had a bit of Loch Ness Monster style fame attracting tourists, photojournalists, and cryptozoologists (insomuch as that is a real thing). Lately though, the moster is fading back to the proper realm of myth and art.

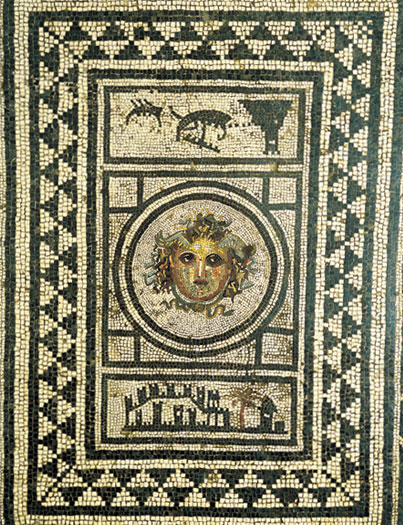

In ancient Greece, one of the most universally popular symbols was the gorgoneion, a symbolized head of a repulsive female figure with snakes for hair. Gorgoneion medallions and ornaments have been discovered from as far back as the 8th century BC (and some archaeologists even assert that the design dates back to 15 century Minoan Crete). The earliest Greek gorgoneions seem to have been apotropaic in nature—grotesque faces meant to ward off evil and malign influence. Homer makes several references to the gorgon’s head (in fact he only writes about the severed head—never about the whole gorgon). My favorite lines concerning the gruesome visage appear in the Odyssey, when Odysseus becomes overwhelmed by the horrors of the underworld and flees back to the world of life:

And I should have seen still other of them that are gone before, whom I would fain have seen- Theseus and Pirithous glorious children of the gods, but so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Proserpine should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon.

In Greco-Roman mythology the gorgon’s head (attached to a gorgon or not) could turn those looking at it into stone. The story of Perseus and Medusa (which we’ll cover in a different post) explains the gorgon’s origins and relates the circumstances of her beheading. When Perseus had won the princess, he presented the head to his father and Athena as a gift—thus the gorgon’s head was a symbol of divine magical power. Both Zeus and Athena were frequently portrayed wearing the ghastly head on their breastplates.

Although the motif began in Greece, it spread with Hellenic culture. Gorgon imagery was found on temples, clothing, statues, dishes, weapons, armor, and coins found across the Mediterranean region from Etruscan Italy all the way to the Black Sea coast. As Hellenic culture was subsumed by Rome, the image became even more popular–although the gorgon’s visage gradually changed into a more lovely shape as classical antiquity wore on.

In wealthy Roman households a gorgoneion was usually depicted next to the threshold to help guard the house against evil. The wild snake-wreathed faces are frequently found painted as murals or built into floors as mosaics.

Not only was the wild magical head a mainstay of classical decoration–the motif was subsequently adapted by Renaissance artists hoping to recapture the spirit of the classical world. Gilded gorgoneions appeared at Versailles and in the palaces and mansions of elite European aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Even contemporary designers and businesses make use of the image. The symbol of the Versace fashion house is a gorgon’s head.

Once again it is the mid-autumn festival (also known as the mooncake festival), one of the most important festivals of the Chinese calendar. I hope you and your friends get together to drink rice wine while looking at the jade rabbit who mixes magic herbs on the moon!

Last year Ferrebeekeeper explored the mid-autumn festival through poetry but this year we will concentrate instead on food. The quintessential foodstuff of the mooncake festival is the mooncake, a cake which is crafted to look like the moon [Ed. this is some fine work you’re doing here], however an equally lunar-looking foodstuff is nearly as important for celebrating the holiday. The pomelo is a beloved citrus fruit which has come to be integrally associated with the mid-autumn festival. The fruit is like a giant green or chartreuse grapefruit with a yellow-white or pinkish-red interior (depending on the variety). Pomelos can be quite large with a diameter that runs between 15 and 30 centimeters (6 to 12 inches) and they can weigh up to 2 kilograms (about 4 and a half pounds). The fruit is segmented like that of an orange (albeit with a great deal more pith) and tastes like a mild sweet grapefruit. In some varieties of southern Chinese cooking, the pomelo skin is used as an ingredient in its own right.

Because of its shape, its harvesting schedule, and its delightful taste, the pomelo is a mainstay of the mid-autumn moon festival. To quote gochengdoo.com, a Chines culture blog:

In Mandarin, pomelos are called 柚子 (you zi), a homophone for words that mean “prayer for a son.” Therefore, eating pomelos and putting their rinds on the head signify a prayer for the youth in the family. In addition, the Chinese believe that by placing pomelo rinds on their heads, the moon goddess Chang’e will see them and respond to their prayers when she looks down from the moon.

The pomelo has long been cultivated in China: the first allusions to the fruit date to 100 BC, but cultivation may go back further. Many of the citrus fruits we are most familiar with, such as oranges, lemons, and limes, are the end result of centuries—or even millennia–of hybridization and selective breeding. Pomelos are an exception. Native to Malaysia and Southeast Asia, the pomelo is one of the ancestral citrus fruit and the pretty trees grow wild in the jungles of Southeast Asia. It is believed that the first sweet oranges were probably a hybridization of pomelos and mandarins. Grapefruits are probably a descendant (it is hard to tell what the exact relations are since citrus trees hybridize so readily). What is certain is that the pomelo fruit is lovely and sweet and will enhance your ability to appreciate the moon tonight!

Happy lunar viewing!

This is the Ferrebeekeeper’s 300th post! Hooray and thank you for reading! We celebrated our 100th post with a write-up of the Afro-Caribbean love goddess, Oshun. To celebrate the 300th post (and to finish armor week on a glorious high note), we turn our eyes upward to the stern and magnificent armored goddess, Athena, the goddess of wisdom.

Athena’s birth has its roots in Zeus’ war with his father Cronus. In order to win his battle against the ruling race of Titans (and thus usurp his father’s place as the king of the gods), Zeus married the Titan Metis, goddess of cunning and prudence. Her wise counsel and crafty stratagems gave the Olympian gods and edge against the Titans and the latter were ultimately cast down. Metis was Zeus’ first wife and the secret to his success… but there was a problem. It was foretold that Metis would bear an extremely powerful offspring: any son she gave birth to would be mightier than Zeus. To forestall this problem Zeus tricked Metis into transforming into a fly and then he sniffed her up his nose so that he could always have her cunning counsel inside his head. But Metis was already pregnant. Inside Zeus’ skull she began to craft a suit of armor for her child to wear. The pounding of her hammer within his temples gave Zeus a terrible headache. Insane with pain, Zeus begged his ally Prometheus (the seer among the Titans) to cure him of this misery through whatever means necessary. Prometheus seized a labrys (a double headed axe from Crete) and struck open Zeus’ head with a noise louder than a thunderclap. In a burst of radiance Athena sprang forth fully grown and clad in gleaming armor.

Athena was Zeus’ first daughter and his favorite child. For his own armor, Zeus had carried an invincible aegis crafted out of the skin of his foster mother, the divine goat Amalthea. When Athena was born he handed this symbol of his invincible power over to her. Similarly throughout classical mythology Athena is the only other entity whom Zeus trusts to handle his lightning bolts (there is an amazing passage in the first lines of the Aneid where she vaporizes Ajax’s chest with lightning, picks him up with a whirlwind, and impales him on a spire of rock in revenge for an impiety). Her other symbols were the owl, a peerless predator capable of seeing at night, and the gorgon’s head, a magical talisman capable of turning humans to stone (which Athena wore affixed to her armor). Although she was first in Zeus’ esteem, Athena did not forget her mother’s fate and she remained a virgin goddess who never dallied with romance of any sort.

Wisdom, humankind’s greatest (maybe our only) strength was Athena’s bailiwick as too were the fruits of wisdom. Athena was therefore the goddess of learning, strategy, productive arts, cities, skill, justice, victory, and civilization. She is often portrayed as the goddess of justified war in opposition to her half-brother Ares, the vainglorious deity representative of the senseless aspects of war. In classical mythology Athena never loses. Her side is always victorious. Her heroes always prosper. She was the Greek representation of the triumph of creativity and intellect.

Metis never bore Zeus a son to usurp him–but when I read classical mythology such an outcome always seemed unnecessary. Not only did Athena wield Zeus’ authority and run the world as she saw fit, but Zeus was perfectly happy with the arrangement (a true testament to her wisdom). The one slight to the grey eyed goddess is that she does not have a planet named after her (nor after her Roman name Minerva), however I have always thought that astronomers have been secretly saving the name. We can use it when we find a planet inhabited by beings of greater intelligence, or when we travel the stars to a second earth and apotheosize into true Athenians.