You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘apotropaic’ tag.

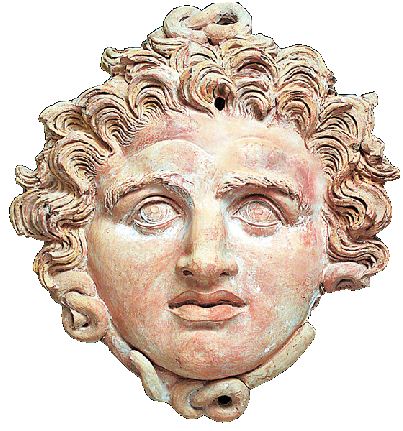

In ancient Greece, one of the most universally popular symbols was the gorgoneion, a symbolized head of a repulsive female figure with snakes for hair. Gorgoneion medallions and ornaments have been discovered from as far back as the 8th century BC (and some archaeologists even assert that the design dates back to 15 century Minoan Crete). The earliest Greek gorgoneions seem to have been apotropaic in nature—grotesque faces meant to ward off evil and malign influence. Homer makes several references to the gorgon’s head (in fact he only writes about the severed head—never about the whole gorgon). My favorite lines concerning the gruesome visage appear in the Odyssey, when Odysseus becomes overwhelmed by the horrors of the underworld and flees back to the world of life:

And I should have seen still other of them that are gone before, whom I would fain have seen- Theseus and Pirithous glorious children of the gods, but so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Proserpine should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon.

In Greco-Roman mythology the gorgon’s head (attached to a gorgon or not) could turn those looking at it into stone. The story of Perseus and Medusa (which we’ll cover in a different post) explains the gorgon’s origins and relates the circumstances of her beheading. When Perseus had won the princess, he presented the head to his father and Athena as a gift—thus the gorgon’s head was a symbol of divine magical power. Both Zeus and Athena were frequently portrayed wearing the ghastly head on their breastplates.

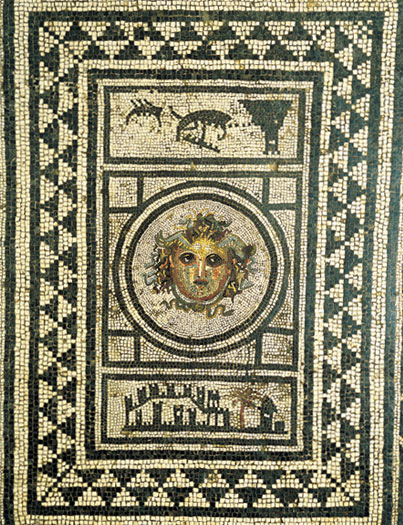

Although the motif began in Greece, it spread with Hellenic culture. Gorgon imagery was found on temples, clothing, statues, dishes, weapons, armor, and coins found across the Mediterranean region from Etruscan Italy all the way to the Black Sea coast. As Hellenic culture was subsumed by Rome, the image became even more popular–although the gorgon’s visage gradually changed into a more lovely shape as classical antiquity wore on.

In wealthy Roman households a gorgoneion was usually depicted next to the threshold to help guard the house against evil. The wild snake-wreathed faces are frequently found painted as murals or built into floors as mosaics.

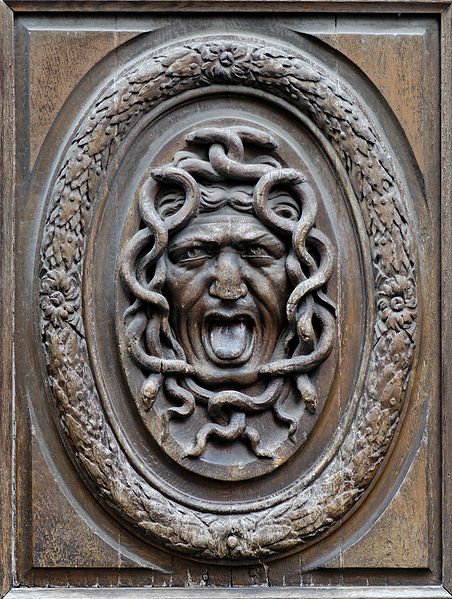

Not only was the wild magical head a mainstay of classical decoration–the motif was subsequently adapted by Renaissance artists hoping to recapture the spirit of the classical world. Gilded gorgoneions appeared at Versailles and in the palaces and mansions of elite European aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Even contemporary designers and businesses make use of the image. The symbol of the Versace fashion house is a gorgon’s head.