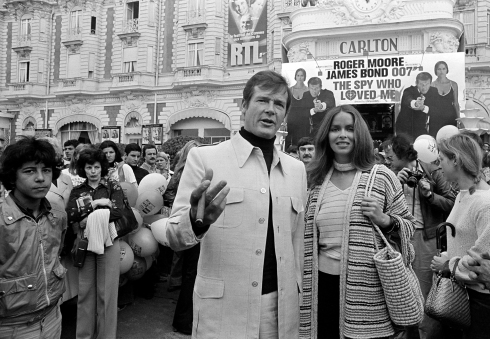

You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘poison’ tag.

Today’s garden-themed post features a flower which I have never planted—indeed, having grown up in farm country, I am somewhat alarmed by this plant. Yet, as I walk around the neighborhood I am beguiled by its seductive beauty (plus there aren’t too many ponies in Brooklyn these days). I am of course talking about the Rhododendrons, a large genus of woody heaths which speciate most prolifically in Asia around the Himalayas, but also can be found throughout Eurasia and into the Americas (particularly the Appalachian Mountains). Actually, I was dishonest in the first sentence (it’s a national fad these days), I have, in fact, planted azaleas, which are a species of rhododendrons, but I am writing here about the big showy purple rhododendrons, and we will leave real talk about azaleas for another spring.

In the In the Victorian language of flowers, the rhododendron symbolizes danger and wariness. This is fully appropriate since some of showiest and most highly regarded rhododendrons are indeed poisonous: they contain a class of chemicals known as grayanotoxins which affect the sodium ion channels in cell membranes. Rhododendron ponticum and Rhododendron luteum are particularly high in grayanotoxins. Humans are somewhat less susceptible to these compounds than other mammals (like poor horses, which just are apt to drop stone dead from browsing on rhododendrons), however, as is so often the case, our cleverness, grabbiness, and our taste for sweetness also puts us at higher risk for consuming grayanotoxins.

Bees are drawn to the large colorful (and sweet) flowers of rhododendrons and they use the grayanotoxin rich pollen and nectar to make honey. If a bee hive incorporates a few ornamental azaleas into the honey, this is not too dangerous, but in regions where rhododendrons dominate and all come into bloom at once, the resultant honey can be extremely dangerous. This “mad honey” is said to cause hallucinations and nausea in lower doses, but in larger quantities it can cause full body paralysis and potentially fatal breathing complications. Like the hellebore, rhododendron honey was one of the first tools of deliberate chemical warfare. Strabo relates that Roman soldiers in the army of Pompey attacking the Heptakometes were undone by honeycombs deliberately left where the sweet toothed Romans would find them. It seems best to appreciate rhododendrons by looking at them. In fact, if you live in a Himalayan fastness surrounded entirely by rhododendron forests (or if you are attacking the Greek people of the Levant) maybe don’t eat honey at all…not until later in the summer.

This lovely little yellow flower is Eranthis hyemalis, more commonly known as the winter aconite. Native to the woodlands of continental Europe, the winter aconite is a member of the sprawling & poisonous buttercup family (which includes beauties and horrors like the monkshood, the ranunculus, and the delphiniums). Eranthis hyemalis which is now blooming here in New York (in gardens which are eccentric enough to have it) is a quintessential spring ephemeral—it blossoms and grows in earliest spring before any trees are in leaf—or even in bloom. The plant flowers and puts out leaves and gathers sunlight and stores energy all before the other plants even start. Then, as the woodland canopy expands above it and as its growing spot is covered with shade, the aconite dies back to its hardy underground tuber which remains dormant until next spring. Although it lives in verdant forests it could almost be an ascetic desert flower based on its hardiness and hermit-like lifestyle. It would be a big mistake to mistake the flower for a weakling or a vegetable–like the other buttercups, all parts of it are ferociously poisonous. Do not eat it (or smoke it…or even look at it funny)!

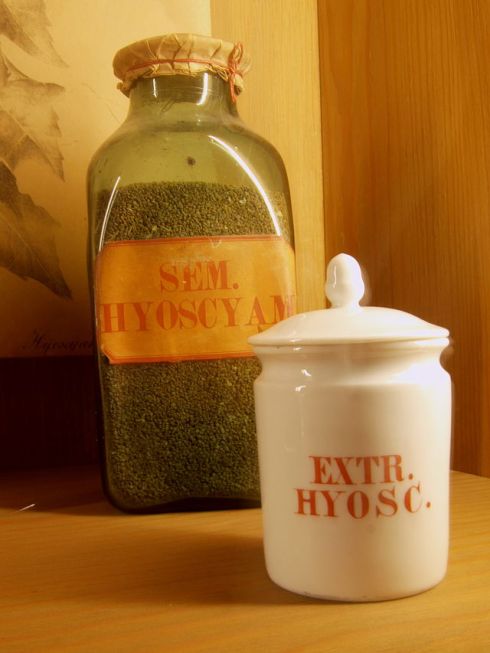

Here is an interesting and horrifying flower! This is henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) which also goes by the name “stinking nightshade.” It is one of the noteworthy poisons of classical antiquity. Henbane is a member of the Solanaceae family—the nightshades—one of the most important of all plant families to humankind. The Solanaceae family includes eggplants, tomatoes, peppers, and potatoes, but also nightshade, datura, and tobacco!

Henbane too is rich in psychoactive alkaloids. Small doses result in dilated pupils, restlessness, flushed skin, and hallucinations. Other symptoms of henbane poisoning include a racing heart, vomiting, extreme body temperature fluctuations, the inability to control one’s muscles, convulsions, coma, and, uh, death, so it’s probably well to steer clear of eating (or touching or taunting) this particular plant. The ancient Greeks and Romans did not read my blog, so they sometimes ingested henbane. In particular, Pliny documented its use by fortunetellers. The priestesses of Apollo would take the plant in order that they might fall into a hallucinogenic trance and then pronounce auguries. It should be noted that priestesses of Apollo tended not to last too well. Henbane also had associations with the world hereafter, and dead souls wandering the margins of the underworld were said to wear henbane laurels.

Henbane originated in southern Europe and western Asia, but classical civilization spread it widely across all of Europe (from whence it traveled to the rest of the world). Incompetent medieval pharmacists used it as an anesthetic and for other sundry “medicinal” uses. It was also popular with poisoners (scholars think it is the most likely candidate to be “hebenon” the poison from Hamlet) and was the means of death for many murders even into contemporary times. It also has a sad place in the witch panics that affected Europe during the dark ages and the early modern era. Witches were said to use it in their potions. Domestic animals would also sometimes eat it accidentally and run wild or perish. Thus witch-hunters would look for the plant and use it as evidence in their trials (although it grows wild as a weed). Also, because of its powerful psychoactive properties, henbane could well give a user the impression of flying and of various supernatural happenings.

On a more mundane level, brewers used henbane to flavor beer until this was recognized as a bad idea (which occurred much later than you might hope) and it was universally replaced with hops. Evidence of henbane’s use as a flavoring agent for beer goes all the way back to the Neolithic era. There is clearly evidence that henbane does something for (to?) humans, but there is even clearer evidence that it is tremendously dangerous and toxic. Maybe it’s best to appreciate this ancient plant through reading about it and looking at pictures of the strange weedy flowers.

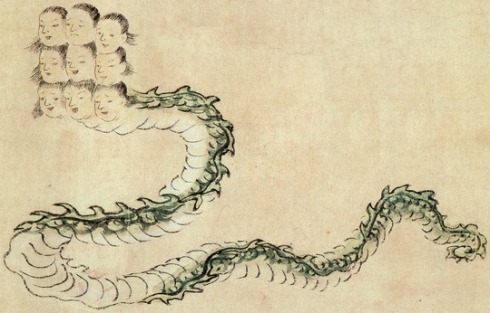

Have you noticed that in life that whenever, after heroic effort, you finally surmount some terrible problem, another problem promptly comes along? Chinese mythology certainly reflects this truth (indeed, after millennia of continuous culture, the Chinese people are quite familiar with the way that one problem slides seamlessly into the next). One of the most harrowing myths from ancient China is the story of Gonggong’s rebellion. You can revisit the whole story here, but the quick version is that the evil water god Gonggong attempted to drown the world and was only prevented from doing so by the heroic last resort actions of the beneficent creator goddess Nüwa, who cut the legs off the cosmic turtle in order to set things to rights.

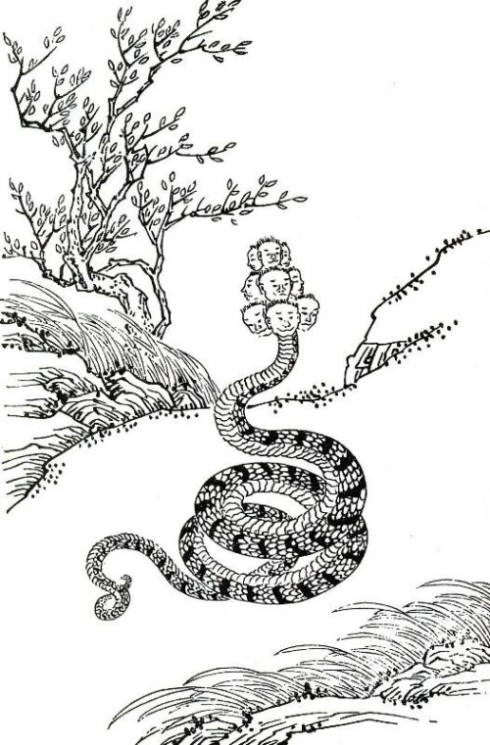

Xiangliu, the nine-headed snake monster, first minister of Gonggong the terrible (not to be confused with Xiang Liu, the Olympic track star)

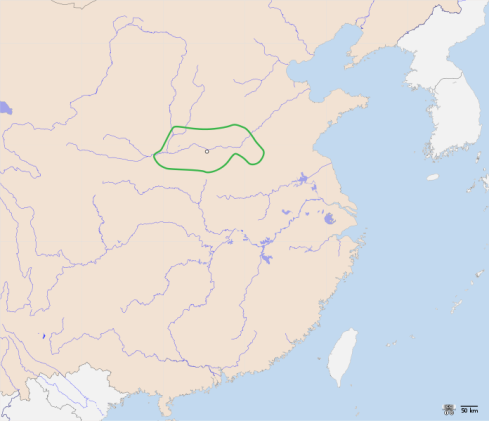

In the chaos of the climactic battle, however Gongong’s chief minister and partner in crime Xiangliu the nine-headed snake monster completely escaped. Filled with bitterness about Gonggong’s failure, Xiangliu crawled away across the soggy lands of Szechuan (which were water-logged after the nearly world-ending floods). Wherever he went, the snake monster left permanent fens and swamps which were toxic to life. His very being had become steeped in poison, and his progress through the damp and moldy world had to be stopped.

Yu the hero, the third of the three sage kings, finally caught up with the nine-headed monster and killed him in a pitched battle . Yet still there was a problem: Xiangliu’s pestiferous blood has poisoned the whole region, which now stank of rot. Crops would not grow and civilization began to falter. Yu dug up the blood soaked soil again and again, but the corrupted blood of the monster just sank deeper into the ground. Finally, Yu excavated a deep valley by Kunlun mountain and rid the world of Xiangliu’s toxins. With all of the land he had excavated he built a great terraced mountain for the gods. Yu then went forth to found the kingdom of Xiam the first civilized state in Chinese history.

Of course some people say that Yu did none of this, that, it was the goddess Nüwa who once again came forth to battle the monster and undo the damage he had caused. Then, with accustomed modesty she let Yu take the credit and begin his kingdom (for Nüwa cared not for empty praise and hollow glory but only for the well-being of her children).

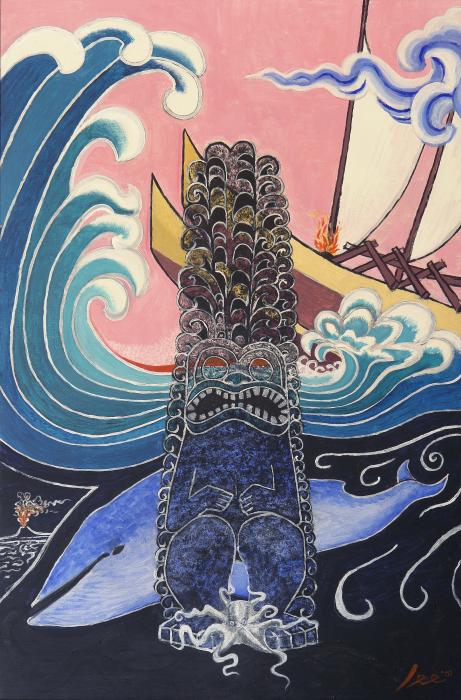

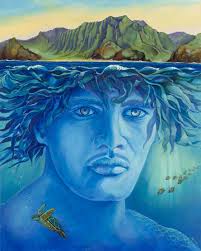

In Hawaiian mythology the most important deity was the beneficent creator god Kāne, the deity of the sun, the dawn, and the fertile forests where people liked to dwell. Yet there was also a deity in opposition to Kāne—an evil god of the dark depths of the ocean, and darkness, and the death of all things. This underworld deity was known as Kanaloa and was sometimes envisioned as a black, poisonous squid or octopus.

The Hawaiian myth of creation involves an art contest of sorts between Kāne and Kanaloa: both deities carved human beings out of basalt but only Kane’s man and woman came to life. Kanaloa’s people remained dark stone. In anger, Kanaloa seduced the first man’s wife and brought enmity between the sexes. The dark deity then invented poison and thus caused many fish, plants, and animals to be injurious to the new humans. Still not satisfied he crafted death so that men and women would have only a short time in the world.

Because of his mischief, Kanaloa was banished to the depths of the ocean, but he retained his power and godhood. Sailors and fishermen pray to Kanaloa so as to remain safe when crossing his watery domain. Likewise he is worshipped as the foremost god of magic. I wish I had some good stories about Kanaloa doing interesting things while in his octopus form, but sadly stories of the dark god are rare. Some ethnologists even suggest that his role was altered and stories about the deity were changed so that he would fit more coherently into missionaries’ stories about God and the Devil.

Happy 407th birthday to Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn! The master’s peerless paintings and etchings show a unique understanding and empathy for the human condition. Rembrandt painted faces more expressively than any other artist–because of this strength, his works attain deep emotional complexity. To illustrate this, and to celebrate his birth, here is a masterpiece by Rembrandt which is in the collection of the Prado Museum in Madrid. The painting is magnificent! A pensive noblewoman (modeled by Rembrandt’s beloved wife Saskia) in resplendent jewels and silks takes a nautilus cup from a little page. Behind her stands a strange gray figure, half-visible in the gloom—an apparition? a servant? The painter himself? It is unclear. The painting itself is a mystery which has been discussed an argued about for centuries.

Rembrandt painted the work in 1634 (which we can see from his prominent signature and his inimitable style), but, uncharacteristically we do not know the title. The painting is either “Artemisia Receiving Mausolus’ Ashes” or “Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Cup.” If the first title is correct, then the nautilus cup which is dramatic focus of the painting contains the ashes of Queen Artemisia’s husband/brother, Mausolus, satrap of Persia. Mausolus’ immense tomb (constructed by Artemisia) was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world and gave us the word “mausoleum”. Yet the great tomb was empty: Artemisia had Mausolus’ ashes mixed into wine which she drank day after day until she had completely consumed his remains (the Greeks were fascinated by the fact that Artemisia was simultaneously the sister and wife and devourer of Mausolus).

However, if the second title is correct, then the seashell cup contains deadly poison. Sophonisba was the daughter of the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal Gisco. Upon his defeat, she took poison so as not to endure the humiliation of being part of a Roman triumph. Nautilus shells allegedly had the magical power to negate poison (safety tip: this is not true at all). That Sophonisba would commit suicide with such a cup indicates the true moral of the painting: the real poison is defeat and slavery. Poison and a proud death are her antidotes.

So which answer is right? Or are they both wrong? Saskia’s strange diffident anxiety could be fitting for either story, yet her manner and dress are not those of a grieving Persian sister-queen. I favor the interpretation of the painting as that of the stoic Sophonisba. These are her last moments and the gray figure is as much an inhabitant of the underworld as a flesh-and-blood attendant. The strange whimsical garb is the fantasy raiment of vanished Carthage. But I could well be wrong. What do you think?

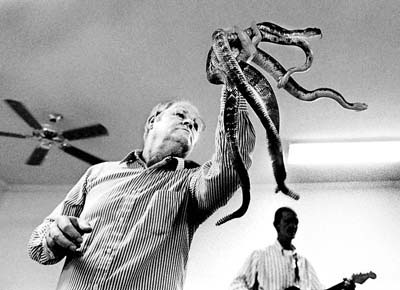

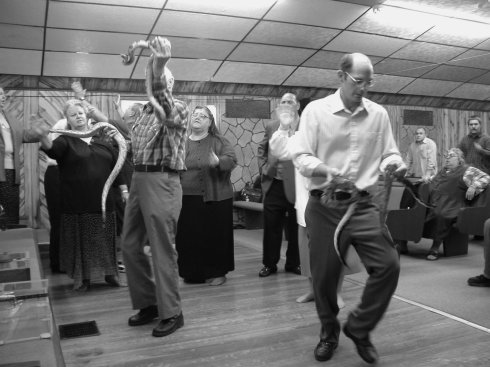

Snake week continues with a dramatic return to my native Appalachia. Up in the mountains, devout Christianity has taken on a great many colorful forms, but arguably none are quite as exciting as the rites celebrated by the Pentecostal Snake-handlers. Snake-handling in Appalachia is said to have a long history rooted in 19th century revivals and tent-show evangelism, but its documented history starts with an illiterate but charismatic Pentecostal minister named George Went Hensley. Around 1910 Hensley had a religious revelation based on two specific New Testament Bible verses. Couched in the flinty vaguely apocalyptic language of the Gospels, the two verses which obsessed Hensley read as follows:

And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues;They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover. Mark 16: 17-18

And he said unto them, I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven. Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you. (Luke 10: 18-19)

While many believers might chose to understand these lines as a general affirmation of Christ’s devotion to his flock, Hensley was very much a literalist (and a showman). Believing that the New Testament commanded the faithful to handle venomous snakes, he set about obtaining a number of poisonous snakes and incorporating them into his ministry. The practice quickly spread along the spine of the mountains and beyond. Even today the Church of God with Signs Following (aka the snake handlers) numbers believers in the thousands.

A service at the Church of God with Signs Following includes standard Pentecostal practices such as faith healing, testimony of miracles, and speaking in tongues (along with much boisterous jumping and testifying), however what sets the ceremony apart are the live poisonous snakes which are located in a special area behind the alter located at the front of the church. Throughout the service, worshipers can come forward and pick up the serpents and even let the snakes crawl over their bodies. Native pit vipers such as copperheads, timber rattlers, and water moccasins are most commonly used in the ceremonies but exotic poisonous snakes like cobras are sometimes included. The snakes act as a proxy for devils and demons. Handling the reptiles is believed to demonstrate power over these underworld forces. If a congregant is bitten (which has happened often), it is usually regarded as an individual or group failure of faith. Upon being bitten devout snake-handlers generally refuse treatment, regarding this as part of their sacrament.

Not only do snake handlers handle snakes they also sometimes drink strychnine to prove their devotion. Additionally (although less alarmingly) they adhere to a conservative dress code of ankle-length dresses, long hair, and no make-up for women, and short hair and oxford shirts for men. Tobacco and alcohol are regarded as sinful.

Snake handling has a long and twisty relationship with state laws. In Georgia, in 1941, state legislators passed a bill which made Pentecostal snake handling into a felony and mandated the death penalty for participants, however the law was so extreme that juries refused to enforce it and it was eventually repealed. A number of states still have old laws clearly designed to curtail the practice of the faith (often these were instituted after particularly controversial deaths, particularly those of children).

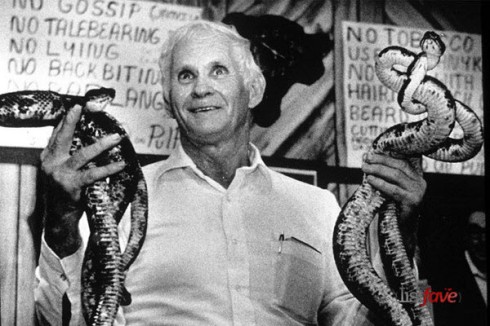

The founder of snake handling, George Went Hensley, also had a twisty serpentine course through life. After founding and popularizing the church during the World War I era, he strayed somewhat from the life of a minister. During the 20’s he had substantial problems in his home life caused by drinking and moonshining. After being arrested for the latter, Hensley was sentenced to work on a chain gang but he beguiled the guards into other duties with his likability and, on an errand to fetch water, he escaped and fled from Tennessee. He worked various occupations including miner, moonshiner, and faith healer and married various women before returning to his ministry in the mid-thirties. During the next decades, Hensley led a vivid life involving a multi-state ministry (which was the subject of a miniature media circus), various drunken fits and conflicts, multiple marriages, and lots of poisonous snakes. The odds caught up to him in Altha, Florida in 1955 when he was bitten on the wrist by a venomous snake which he had removed from a lard can and rubbed on his face. After becoming visibly ill from the bite, he refused treatment (and is said to have rebuked his congregation for their lack of faith) before dying of snakebite. When he died he had been married 4 times and fathered 13 known children. He also had claimed to have been bitten over 400 times by various snakes.

Hensley always asserted that he was not the father of snake-handling, however he certainly popularized the movement. Even today, Christians of a certain mindset can prove their faith by harassing toxic reptiles (although the religion’s legality is disputed in many states where it is practiced).

The world’s largest hornet is the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). An individual specimen can measure up to40 mm (1.6 inches) long with a wingspan of 60 mm (2.5 inches). Giant hornets have blunt wide heads which look different from those of other wasps, hornets, and bees and they are colored yellow orange and brown.

The Asian giant hornet ranges from Siberia down across the Chinese coast into Indochina and lives as far west as India, however the hornet is most common in the rural parts of Japan where it is known as the giant sparrow bee. The sting of the Asian giant hornet is as oversized as the great insect is. Within the hornet’s venom is an enzyme, mastoparan, which is capable of dissolving human tissue. Masato Ono, an entomologist unlucky enough to be stung by the creature described the sensation a “a hot nail through my leg.” Although the sting of a normal honey bee can kill a person who is allergic to bees, the sting of an Asian giant hornet can kill a person who has no allergies–and about 70 unfortunate souls are killed by the hornets every year.

Armed with their size and their fearsome sting, Asian giant hornets are hunters of other large predatory insects like mantises and smaller (i.e. all other) hornets. The giant hornets do not digest their prey but masticate it into a sticky paste to feed to their own offspring. A particular favorite prey is honey bee larvae, and since European honey bees have no defense against the giant wasps, all efforts by Japanese beekeepers to introduce European bees have met with failure. Japanese honey bees however have evolved a mechanism (strategy?) to cope with hornet incursion. When a hive of Japanese honey bees detects the pheromones emitted by hunting hornets, a crowd of several hundred bees will form a gauntlet (carefully leaving a space for the hornet to enter). Once the hornet walks into the trap the bees rush on top of it and grasp it firmly. They then begin to vibrate their flight muscles which raises the temperature and produces carbon dioxide. Since giant hornets cannot survive the CO2 levels or high temperatures that honey bees can, the hornets put up a titanic struggle to overcome the mass of bees, killing many in the process. However honey bees have a fanaticism which would do credit to the most ardent practitioner of Bushido, and they usually kill the invaders.