You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘ornament’ tag.

To take our minds off of the cabin fever of being stuck at home (in a pandemic…in the snow), today’s post features one of the world’s most extravagant and beautiful buildings. This complex is Wat Rong Khun, the white temple of Chiang Rai in Northern Thailand. Sources inform me that it actually totally exists, right here in the real world (although I find it somewhat difficult to believe such a thing, because, well, just look at it!).

Wat Ron Khun was an extant Buddhist temple (one of thousands throughout Southeast Asia) which, by the end of the twentieth century, had fallen into disrepair. In 1997, Thai visionary artist Chalermchai Kositpipat restored/rebuilt the temple into the fantastical form which you see in these photos. Interestingly Wikipedia now balks at calling Wat Rong Khun a temple and instead describes the complex as “a privately owned art installation” where people can meditate and learn about Buddhist teachings (and which is intended to ingratiate Kositpipat into Buddha’s good graces and ensure immortal life for the artist). Hmm… How is that different from just saying “temple”?

Anyway, the bridges, gates, and buildings of Wat Rong Khun are all white or reflective with one big exception. The building which houses the compound bathrooms are gold. The white/mirror colors reflect the mind and the intellect–colorless, pure, and abstract. The bathroom compound however is gold to contextualize worldly and physical concerns (such as material wealth).

Gardens aside, the other non-monochrome portion of the compound is found in the main ubosot, where mind-bendingly strange murals illustrate the human condition. These murals are not as, uh…restrained (?) as the rest of the wat, and I will write about them later when I feel stronger. Suffice it to say that if anything belonged inside this squirming albescent nirvana-cake, it is the paintings which are indeed in there.

Although I suppose I should be comparing Wat Rong Khun with Wat Pa Maha Chedio Kaew (the “temple of a thousand bottles”) what it truly reminds me of is Orvieto Cathedral, another installation/temple which is completely bedazzled with mind-altering religious ornamentation (and which features insane hell frescoes inside). Let’s all get vaccinated so we can go to some of these places in the real world (assuming they can indeed actually be found there).

Turkey Hood Ornament?

Thanksgiving time is upon us already! I know this because I spent tonight making a cake for the office potluck instead of writing about turkey virgin birth or whatever. However, even if I got distracted, I haven’t forgotten these magnificent birds. Here is a little gallery of turkey ornaments from around the internet (and throughout time) to help you get in the holiday mood.

What could be more American than turkeys in a jeweled car made of corn?

These are pretty, I wonder what they are for…

These guys have a first generation Oldsmobile! What is it with turkeys and cars?

Speaking of which, this looks like another hood ornament.

Turkey lights?? Sign me up!

What? That’s a kiwi! Stay in your lane, New Zealand!

That’s more like it!

this one is cute!

Oh no! The poor bird! What have they done to you? [surreptitiously licks lips]

One theory of aesthetics asserts that every human-manufactured item provides profound insights into its makers and their society. In college, we had endless fun (or some reasonably proximate substitute) by grabbing random kitschy mass-produced objects and deconstructing them so that all of the peccadillos of wage-capitalism in a mature democracy were starkly revealed. Alone among college endeavors, this proved useful later on, when I worked at the National Museum of American History (where the staff was employed to do more-or-less the same thing). Seemingly any item could provide a window for real understanding of an era. Thus different aspects of our national character were represented by all sorts of objects: harpoons, sequined boots made in a mental asylum, an old lunch-counter, gilded teacups, or miniature ploughs…even a can of Green Giant asparagus from the 70s [btw, that asparagus caused us real trouble and was a continuing problem for the Smithsonian collection: but we will talk about that later on in an asparagus-themed post]. The objects which were significant were always changing and things regarded as treasures in one era were often relegated to the back of off-site storage facility by curators of the seceding generation, but a shrewd observer could garner a surprisingly deep understanding of society by thinking intelligently about even apparently frivolous or trivial objects.

Anyway, all of this is roundabout way of explaining that Ferrebeekeeper is celebrating the Day of the Dead by deconstructing these two skull-themed items. At the top is a skull-shaped candle holder with a bee on it. At the bottom is a skull shaped lotion-dispenser. One dispenses light while celebrating the eusocial insects at the heart of agriculture; the other dispenses unguents and celebrates the reproductive organs of plants. But of course, when we look at these items more closely, there is more to them than just a decorated lamp and a cosmetics container.

The Día de Muertos skull already represents a syncretic blend of two very opposite cultures: the death-obsessed culture of the Aztecs who built an empire of slavery and sacrifice to make up for dwindling resources at the center of their realm, and the death-obsessed culture of the Spaniards who built an empire of slavery and sacrifice to make up for dwindling resources at the center of their realm. Um…those two civilizations sounded kind of similar in that last sentence, but, trust me, they were from different sides of an ocean and had very different torture-based religions.

Beyond the obvious cultural/religious history of Mestizo culture, the two skulls have bigger things to say about humankind’s relationship with our crops. The features of the death’s head have been stylized and “cutened” but even thus aestheticized it provides a stark reminder of human mortality. We burgeon for a while and then pass on. Yet the day of the dead skull is a harvest-time ornament. It is made of sugar or pastry (well not these two…but the original folk objects were) and covered in flowers, grain, and food stuffs. The skulls portray humankind as a product of our agricultural society. The harvest keeps coming…as do seceding generations of people…just as the old harvest and the old people are used up—yet they are always a part of us like a circle or an ouroboros. Each generation, a different group of people comes to work the fields, and eat sugar skulls and pass away–then they are remembered with sugar skulls as their grandchildren work the fields etc…

Lately though, things have started to rapidly change. Although agriculture is the “primary” economic sector which allows all of the other disciplines, most of us no longer work in the fields. Instead we partake of secondary sector work: manufacturing things. In this era we are even more likely to be in the third (or fourth) sector: selling plastic skulls to each other, or writing pointless circular essays about knickknacks.

Marketers have inadvertently built additional poignant juxtapositions into these two skull ornaments. The skull at the bottom is a lotion or soap dispenser. It is meant to squirt out emollients so that people can stay clean and young and supple in a world where old age still has no remedy. The irony is even more sad in the skull on the top which shows a busy bee: the classical symbol of hard work paying off. Yet the bees are dying away victims to the insecticides we use to keep our crops bountiful. Hardwork has no reward in a world where vast monopolistic forces set prices and machines churn out endless throw-away goods. Indeed, these two objects are not beautiful folk objects…they are mass-produced gewgaws meant to be bought up and thrown away. In the museum of the future will they sit on a shelf with a little note about bees or lotion or crops written next to them, or will they join a vast plastic underworld in a landfill somewhere?

Or maybe they are just endearing skulls and you aren’t supposed to think about them too much. But if a skull does not make the observer think, then what object ever will?

Yesterday’s post for World Oceans Day did not sate my need to write about the endless blue bounding. I am therefore dedicating all of the rest of this week’s blog posts to marine themes as well (“marine” meaning relating to the sea—not the ultimate soldiers). Today we are traveling back to South America to revisit those masters of sculpture, the Moche, a loose federation of agricultural societies which inhabited the Peruvian coastal valleys from 100 AD – 900 AD.

I keep thinking about the beauty and power of Moche sculptural art, and the Moche definitely had strong feelings about the ocean. In fact an informal survey of Moche art online indicates that their favorite themes were cool-looking animals, human sacrifice, the ocean, grown-up relations between athletic consenting adults, and crazy nose-piercings.

You will have to research some of these on your own, but I have included a selection of beautifully made Moche art of sea creatures. Look at the expressiveness of the crab, the turtle, and particularly the beautiful lobsters (which are part of a large pectoral type ceremonial ornament held in place through the nose). Moche ceramics are as rare and beautiful in their way as Roman paintings or Greek sculpture. I wish we knew more about Moche culture and mythology to contextualize these striking works—but the outstanding vigor and grace of the figures is enough to feel something of what this vivid culture was like.

The silver-gilt coronet of the 14th Earl of Kintore (you could have bought it at Christie’s for less than a used Trans Am)

A coronet is a small crown which is worn by a nobleman or noblewoman. In the European tradition coronets differ from kingly crowns in that they lack arches—they are instead simple rings with ornaments attached. Different ranks of nobility wear different coronets. For example, in England the various ranks are denoted as follows:

Marquess: that of a marquess has four strawberry leaves and four silver balls (known as “pearls”, but not actually pearls)

If you bothered counting the “pearls” and strawberry leaves on the above illustrations, you will recognize that certain adornments have been left out (which is to simplify the heraldic representation of coronets). I wish I knew what the strawberry leaves represent! If I was a sinister & bloodthirsty nobleman, that is not the sort of decoration I would choose for my fancy fancy hat, but maybe I am not thinking like a peer. Other western European nations have differently shaped coronets with different ornaments, but the same sort of rank-by-decoration pertains.

Coronets are largely symbolic—many nobles do not even have them made. By tradition they are worn only at the coronation of a monarch. Coronets are important however in heraldry, and the peerage rank of a noble house can easily be determined by looking at the little crown drawn on their shield.

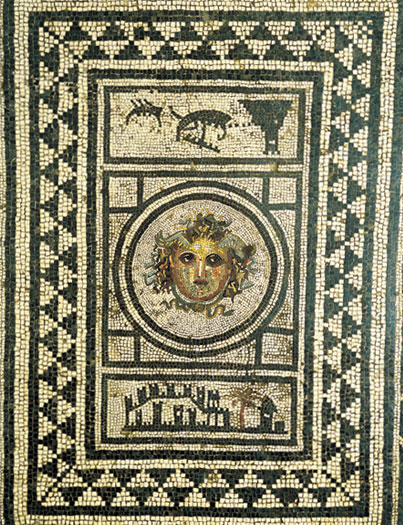

In ancient Greece, one of the most universally popular symbols was the gorgoneion, a symbolized head of a repulsive female figure with snakes for hair. Gorgoneion medallions and ornaments have been discovered from as far back as the 8th century BC (and some archaeologists even assert that the design dates back to 15 century Minoan Crete). The earliest Greek gorgoneions seem to have been apotropaic in nature—grotesque faces meant to ward off evil and malign influence. Homer makes several references to the gorgon’s head (in fact he only writes about the severed head—never about the whole gorgon). My favorite lines concerning the gruesome visage appear in the Odyssey, when Odysseus becomes overwhelmed by the horrors of the underworld and flees back to the world of life:

And I should have seen still other of them that are gone before, whom I would fain have seen- Theseus and Pirithous glorious children of the gods, but so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Proserpine should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon.

In Greco-Roman mythology the gorgon’s head (attached to a gorgon or not) could turn those looking at it into stone. The story of Perseus and Medusa (which we’ll cover in a different post) explains the gorgon’s origins and relates the circumstances of her beheading. When Perseus had won the princess, he presented the head to his father and Athena as a gift—thus the gorgon’s head was a symbol of divine magical power. Both Zeus and Athena were frequently portrayed wearing the ghastly head on their breastplates.

Although the motif began in Greece, it spread with Hellenic culture. Gorgon imagery was found on temples, clothing, statues, dishes, weapons, armor, and coins found across the Mediterranean region from Etruscan Italy all the way to the Black Sea coast. As Hellenic culture was subsumed by Rome, the image became even more popular–although the gorgon’s visage gradually changed into a more lovely shape as classical antiquity wore on.

In wealthy Roman households a gorgoneion was usually depicted next to the threshold to help guard the house against evil. The wild snake-wreathed faces are frequently found painted as murals or built into floors as mosaics.

Not only was the wild magical head a mainstay of classical decoration–the motif was subsequently adapted by Renaissance artists hoping to recapture the spirit of the classical world. Gilded gorgoneions appeared at Versailles and in the palaces and mansions of elite European aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Even contemporary designers and businesses make use of the image. The symbol of the Versace fashion house is a gorgon’s head.