You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Homer’ tag.

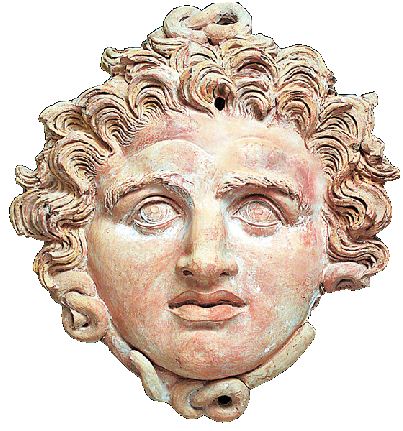

In ancient Greece, one of the most universally popular symbols was the gorgoneion, a symbolized head of a repulsive female figure with snakes for hair. Gorgoneion medallions and ornaments have been discovered from as far back as the 8th century BC (and some archaeologists even assert that the design dates back to 15 century Minoan Crete). The earliest Greek gorgoneions seem to have been apotropaic in nature—grotesque faces meant to ward off evil and malign influence. Homer makes several references to the gorgon’s head (in fact he only writes about the severed head—never about the whole gorgon). My favorite lines concerning the gruesome visage appear in the Odyssey, when Odysseus becomes overwhelmed by the horrors of the underworld and flees back to the world of life:

And I should have seen still other of them that are gone before, whom I would fain have seen- Theseus and Pirithous glorious children of the gods, but so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Proserpine should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon.

In Greco-Roman mythology the gorgon’s head (attached to a gorgon or not) could turn those looking at it into stone. The story of Perseus and Medusa (which we’ll cover in a different post) explains the gorgon’s origins and relates the circumstances of her beheading. When Perseus had won the princess, he presented the head to his father and Athena as a gift—thus the gorgon’s head was a symbol of divine magical power. Both Zeus and Athena were frequently portrayed wearing the ghastly head on their breastplates.

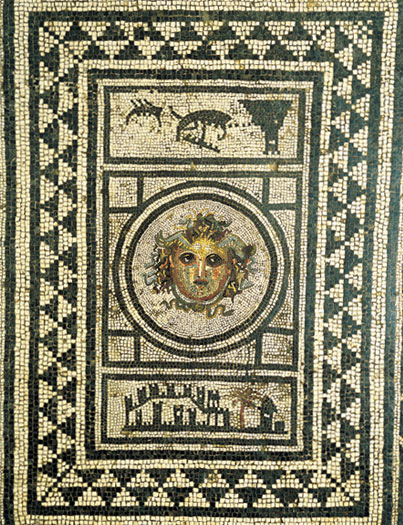

Although the motif began in Greece, it spread with Hellenic culture. Gorgon imagery was found on temples, clothing, statues, dishes, weapons, armor, and coins found across the Mediterranean region from Etruscan Italy all the way to the Black Sea coast. As Hellenic culture was subsumed by Rome, the image became even more popular–although the gorgon’s visage gradually changed into a more lovely shape as classical antiquity wore on.

In wealthy Roman households a gorgoneion was usually depicted next to the threshold to help guard the house against evil. The wild snake-wreathed faces are frequently found painted as murals or built into floors as mosaics.

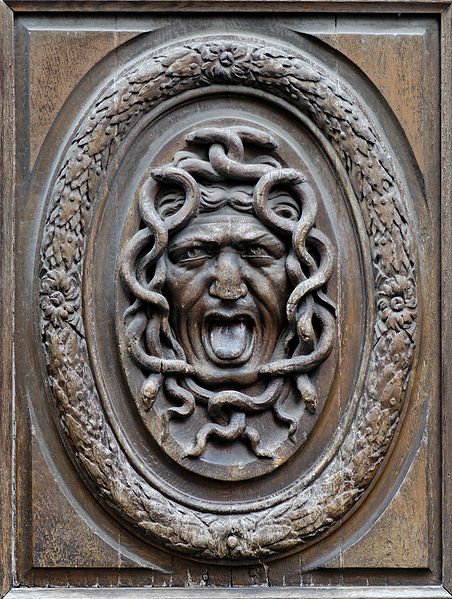

Not only was the wild magical head a mainstay of classical decoration–the motif was subsequently adapted by Renaissance artists hoping to recapture the spirit of the classical world. Gilded gorgoneions appeared at Versailles and in the palaces and mansions of elite European aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Even contemporary designers and businesses make use of the image. The symbol of the Versace fashion house is a gorgon’s head.

Asphodels are a genus (Asphodelus) of small to mid-size herbaceous perennial flowers. Originally native to southern and central Europe, the flowers now grow in other temperate parts of the world thanks to flower gardeners who planted them for their white to off-white to yellow flowers and their eerie grayish leaves. These leaves have long been used to wrap burrata, a fresh Italian cheese made of cow’s milk, rennet and cream—when the asphodel leaves dried out the cheese was known to be past its prime. The bulblike roots of asphodel are edible and were eaten by the poor during classical antiquity and the middle ages until the potato was introduced to Europe and supplanted asphodel completely.

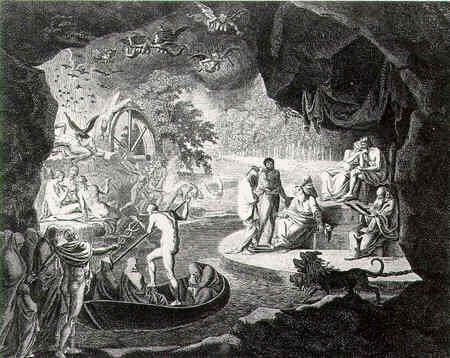

This somewhat pedestrian wildflower is one of the most famous plants connected to the Greco-Roman underworld. Homer is the first poet (whose works still survive) to give a lengthy description of the realm of Hades and the asphodel is mentioned growing everwhere in a great field in the middle of the underworld. To quote the University of Missouri Museum of Art and Archaeology website:

Largely a grey and shadowy place, the Underworld was divided into three parts. Most souls went to the “Plains of Asphodel,” an endless stretch of twilit fields covered with grey and ghostly asphodel flowers, which the dead ate. A very few chosen by the gods spent their afterlife in the “Fields of Elysium,” a happier place of breezy meadows. But if the deceased had committed a crime against society, his/her soul went to Tartarus to be punished by the vengeful Furies until his debt to society was paid, whereupon he/she was released to the Plains of Asphodel…. Souls of the dead were only a pale reflection of their former personality, often portrayed as twittering, bat-like ghosts, physically diaphanous and insubstantial.

The gray and ghostlike nature of the asphodel plant and its wistful off-white flower may have suggested something funereal to the ancient Greeks. Or possibly the plant’s connection with the afterlife was a hand-me-down from an earlier culture. In fact here is a learned and comprehensive scholarly essay which posits that the asphodel had pre-Greek religious significance.

Whatever its history, the Greeks also regarded the plant as sacred to Persephone/Proserpine, who is frequently portrayed wearing it or picking it, as well as to other chthonic deities. Greeks and Romans planted asphodel on tombs both for its melancholy beauty and as a sort of food offering to the dead. So the cemeteries of classical antiquity were lugubrious but pretty places filled with ghostly flowers.

In western literature and art asphodel remains a symbol of mourning, death, and loss. William Carlos Williams made the plant the central focus of his poem “Asphodel, the Greeny Flower” which agonizes over the ambiguities of the next world (which seems to be a land of oblivion) juxtaposed with the burning regrets of this life. Here is a poignant fragment:

Of asphodel, that greeny flower, like a buttercup upon its branching stem- save that it's green and wooden- I come, my sweet, to sing to you. We lived long together a life filled, if you will, with flowers. So that I was cheered when I came first to know that there were flowers also in hell. Today I'm filled with the fading memory of those flowers that we both loved, even to this poor colorless thing- I saw it when I was a child- little prized among the living but the dead see, asking among themselves: What do I remember that was shaped as this thing is shaped? while our eyes fill with tears. Of love, abiding love it will be telling though too weak a wash of crimson colors it to make it wholly credible. There is something something urgent I have to say to you and you alone but it must wait while I drink in the joy of your approach, perhaps for the last time.

One of the most enigmatic Greek divinities is Nyx, the primordial goddess of the Night. In Hesiod’s Theogeny she was a child of Chaos, but, in other texts, Nyx was present at (or before) creation and had no parents. She is rarely mentioned in classical texts, but the few times she does appear are noteworthy. Some of her children include Death (Thanatos), Sleep (Hypnos), Mockery (Momus), Dreams (Morpheus), and the Fates (Moirae)–they represent various slantwise forces which even the Olympian gods are subject to.

One of the most enigmatic Greek divinities is Nyx, the primordial goddess of the Night. In Hesiod’s Theogeny she was a child of Chaos, but, in other texts, Nyx was present at (or before) creation and had no parents. She is rarely mentioned in classical texts, but the few times she does appear are noteworthy. Some of her children include Death (Thanatos), Sleep (Hypnos), Mockery (Momus), Dreams (Morpheus), and the Fates (Moirae)–they represent various slantwise forces which even the Olympian gods are subject to.

Nyx is mentioned in Chapter XIV of Homer’s Illiad, when the sleep god Hypnos refuses to carry out Hera’s bidding. Hypnos describes the past results of putting Zeus to sleep (against Zeus’ will) and relates how his mother saved him:

“Jove was furious when he awoke, and began hurling the gods about all over the house; he was looking more particularly for myself, and would have flung me down through space into the sea where I should never have been heard of any more, had not Night who cows both men and gods protected me. I fled to her and Jove left off looking for me in spite of his being so angry, for he did not dare do anything to displease Night. And now you are again asking me to do something on which I cannot venture.” [Forgive the Roman names—I used the Johnson translation for ease of citation and copying. Also, obviously, Nyx is called “Night” as she is in the rough Aristophanes quote below. I’ll try to find some prettier translations later.]

Nyx is also mentioned in Orphic cult poetry (certain mystery cult poems were attributed to the demigod Orpheus) where she is portrayed as a bird/woman with black wings who first created the universe. She dwells in a cave at the edge of the Cosmos. With her in the eternal darkness is Kronos, Zeus’ father, who was savagely mutilated by his son. Kronos is unconscious, drunk on magical honey, and he mutters prophecies which Nix then chants. Outside the cave is Zeus’ nursemaid, Adrasteia, who acted as mother for the king of the gods during his boyhood. Adrasteia keens and beats a cymbal to Nyx’s chanting and the entire universe subtly moves to the rhythm of her cymbal.

Aristophanes alludes to the Orphic mystery poetry in a chorus from his play “The Birds”. The chorus is sung by birds who have a different take on creation. In their interpretation, night is a bird and they are descended from her via love and chaos. Here is the relevant portion of their song:

…At the start,

was Chaos, and Night, and pitch-black Erebus,

and spacious Tartarus. There was no earth, no heaven,

no atmosphere. Then in the wide womb of Erebus,

that boundless space, black-winged Night, first creature born,

made pregnant by the wind, once laid an egg. It hatched,

when seasons came around, and out of it sprang Love—

the source of all desire, on his back the glitter

of his golden wings, just like the swirling whirlwind.

In broad Tartarus, Love had sex with murky Chaos.

From them our race was born—our first glimpse of the light

not before Love mixed all things up. But once they’d bred

and blended in with one another, Heaven was born,

Ocean and Earth—and all that clan of deathless gods.

Thus, we’re by far the oldest of all blessed ones,

for we are born from Love. There’s lots of proof for this.

We fly around the place, assisting those in love—

[Translation by Ian Johnston]

Although a few small temples and cults to Nyx existed, she was not often worshiped openly in Greece (nor, for that matter, were her children). However Nyx was in the background of many other god’s temples and ceremonies as a statue or a sacred phrase. Around her name and mythos was an impalpable shroud of ambiguity. To the Greeks, Nyx was older and stranger than the gods they cared about and worshiped–she was the first and original outsider.