You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Cuttlefish’ tag.

Last week I finished up the AtlasObscura course on cephalopods, a Zoom mini-survey of this astonishing class of mollusks. The course was a delightful romp through morphology, taxonomy, paleontology, and ecology and featured some virtuous side lessons about how to protect Earth’s ecosphere (and ourselves).

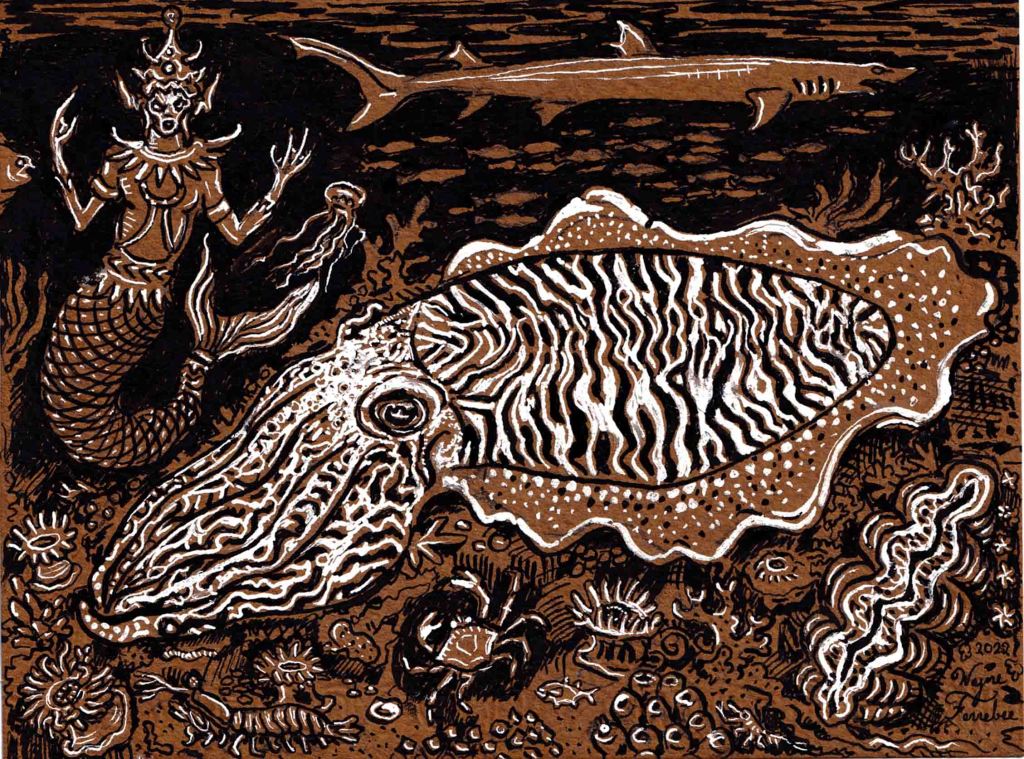

The incredible diversity, beauty, and wonder of cephalopods reminded me that I have not blogged about them…or any molluscs…or anything else for far too long. Ergo, as a promise of more posts to come, here are two little cephalopod drawings I made to share with the class.

The first picture (top) is an Indo-Pacific cuttlefish enjoying the reef and trying to overlook the whimsical Thai/Malay merman who has appeared out of the realm of fantasy (note also the reef shark, giant clam, and mantis shrimp). The second image (as per “homework” instructions) is a cooperoceras flashing iridophores which it may or may not have had as various lower Permian sea creatures (most notably Helicoprian) look on in dazzled envy.

We will talk more about these creatures in weeks to come (and maybe more about the Permian too, since I keep thinking about how the Paleozoic ended), but for now just enjoy the little tentacled faces! Also, it is “inktober” and I have been obsessed with classic pen and ink, so maybe get ready for more drawings as well (to say nothing of our traditional Halloween theme week, which will be coming up quite soon).

Exciting news from the world of mollusk research! Scientists have discovered new insights into how cuttlefish blend in so seamlessly with their underwater world. Cuttlefish are chameleons of the undersea realm: they have the ability to change their color and texture in order to blend in with seaweed, coral, the ocean floor or whatever habitat they encounter. Yet, even more remarkably, they can mimic the rough coloration and shape of other organisms, thereby fooling predators and prey by mimicking crabs and fish.

Cuttlefish copy the textures they find in their environment by means of small nodules known as papillae. The cephalopods extend and retract these intricate bumps using muscles. They can become perfectly smooth in order to maximize their speed and maneuverability or they can take on the texture of rocks, coral, or even seaweed. Scientists have discovered that the cuttlefish accomplishes this not by means of continuous concentration, but instead with muscles which can be locked in place by means of certain neurotransmitters (it pays not to contemplate the vivisection through which this knowledge was obtained). If a cuttlefish takes on a certain texture and then promptly loses use of the relevant muscle nerve, the neurotransmitters remain active and it takes hours for the creature’s metabolism to return it to its neutral shape.

This may seem like a minor insight, but learning that cuttlefish (and presumably the squids and octopuses which use the same sort of papillae to alter their texture) are utilizing a muscle trick which is not unlike mechanism by which clams lock their shells in place is another step in unlocking the mysteries of these remarkable tentacled masters of disguise.

I hope you had a wonderful Thanksgiving, but, oof, the Monday after Thanksgiving is always a rough day. The holiday season has just started—but hasn’t gotten fun yet (my tree is badly assembled with no lights or ornaments—the cats have been climbing through it like gibbons in a hatrack and have knocked it over once already). Additionally, the quotidian dictates of work combine with the gray bleakness of November to create a feeling of malaise which makes blogging difficult. Also, it is 11:30 PM already. What the jazz?

To combat these problems and get something down on paper (and to kick off the holiday season?) here is a visual post—a gallery of incredible vibrant cuttlefish from the world’s warm seas. Hopefully there color will bring some pizzazz to your day. Finding them online actually helped me get back in the groove.

The flamboyant cuttlefish—the purple and yellow master of poison–rightfully has pride of place at the very top of the post, however there are some cuttlefish which I haven’t written about here too. As soon as I have a bit more time I will come back and write about them. As we get into December we will have more exciting and thoughtful posts which aren’t a placeholder like this one.

Also, I am still working on the thrilling project which I teased earlier (although, like everything, it is taking longer than I planned). For now, enjoy this little rainbow of sorbet tentacles and w-shaped eyes. It’s going to be a merry holiday season and there are wonders ahead of us. First we have to get a bit further into the workweek though….

Last Friday I took a walk from my company’s office on Wall Street up to a dinner party in Alphabet City. It was a lovely foggy night and lower Manhattan looked splendid and foreboding: the skyscrapers disappeared into the clouds as though they had no tops and weird glowing halos wreathed the many lights of the finance district. I decided to walk through City Hall Park (which has a big Victorian fountain surrounded by flickering gaslamps which I like to look at), however, when I walked into the park I was stunned to see a large photoshopped sculpture/poster thing of two enormous cuttlefish mating on the entire planet! What could it mean? Has the mayor been reading Ferrebeekeeper? Have the cephalopods finally won a stake in city government?

![20170714_201949[1]](https://ferrebeekeeper.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/20170714_2019491.jpg)

(also note the ammonite patterns on this shirt my mom made me)

Here is a shameless selfie of me with the aforementioned work…and it turned out it was not alone: the whole park was full of tentacles, sticky lizard limbs, and planetary bodies.

These sculptures are the environmentally themed artworks of Estonian artist, Katja Novitskova. I had wandered into her show by accident! She used digital technology (and microscopes and satellite imaging) to bring us a juxtaposition of small curious grasping creatures against a background of entire worlds. She particularly specializes in creatures which are the subject of extensive biomedical or biomechanical research—literal and figurative model organisms like the axolotl, the cuttlefish, and the little hydra.

“EARTH POTENTIAL” (Katja Novitskova, 2017, mixed media sculpture)

This theme is much in keeping with my own artwork which involves biological and historical cycles seen at differing temporal and spatial vantages. Yet because her works are so colorful and pleasing (and so photographic and digital) I am not inclined to view the successful Miss Novitskova with envy. The photographic sculptures remind me of Ranger Rick, the wonderful ecology-themed magazine of my childhood which always featured a “What in the World?” section of photographic sections removed from their original context and blown up. It was a real puzzle to figure out if you were looking at a vascular wall, a butterfly wing, or an aerial photo of the Nile Delta. Just thinking about these different scales (and the discomfiting similarities of appearance and perhaps even function) always blew my mind. So does Katja Novitskova’s artwork! I would like to thank her for putting it up in New York and wish her every success.

EARTH POTENTIAL (Katja Novitskova, 2017, mixed media sculpture)

The Australian giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama) is the world’s largest cuttlefish. Specimens can measure up to 50 centimeters in length and weigh up to 10 kilograms (23 pounds). Like other cuttlefish, the giant cuttlefish are masters of color transformation and can use the chromatophores (special transformative muscle cells) in their skin to instantly change the hue, reflectivity, polarization, and even the shape of their skin. They use this ability for hunting, hiding from predators, and for spectacular mating displays. Indeed, the giant cuttlefish is a remarkable animal in many ways, but, above all, it is notable for its operatic sex life!

Sepia apama ranges in all coastal habitats from Brisbane on the Pacific to Shark Bay on the Indian Ocean (effectively the entire southern coast of the continent). Thanks to jet propelled speed, color-transforming ability, sharp eyesight, high intelligence, and lightning fast grab jaws (which are located on two extendable arms), these cuttlefish are terrifyingly effective hunters of fish and crustaceans. Australian giant cuttlefish from different regions of the coast do not interbreed, even though they are genetically the same species. Like humans, the giant cuttlefish seem to form different sorts of societies with different mating customs: for example the giant cuttlefish of the Spenser Gulf region are unique (apparently among all cuttlefish) in that they join together for a spawning aggregation in the waters immediately around Point Lowly.

Unlike humans, there are eleven male cuttlefish for every single female giant cuttlefish! Large dominant male cuttlefish carve out territories with aggressive posturing and insanely bright flashing color displays. Smaller males (who do not wish to be ripped apart), distract the alpha male cuttlefish by adapting the color schemes of female cuttlefish and courting him. They then abruptly change color and pay (rapid) court to the polyandrous females. The female stores sperm packets from several males and she chooses the paternity of her offspring only after she lays her eggs. Cuttlefish are semelparous—they mate only once, and then they immediately die. The whole beautiful horrifying op-art orgy in the waters around Point Lowly is of paramount importance—and is also reckoned to be one of the unrivaled diving spectacles of the world.

Unfortunately all of the Spenser Gulf cuttlefish tend to be in one place at once. Since they only reproduce one time, they are very vulnerable to fisherman, who, up until the mid nineties, descended upon the area, captured most of the cuttlefish, and chopped them into bate for snappers. When one cohort was removed, the next was seriously attenuated!

Fortunately the spawning waters of Spenser Gulf are now a protected refuge, yet hydrological changes, agricultural run-off, and industrial development could still threaten the entire population. Perhaps the other Australian Giant Cuttlefish (who conduct their romantic affairs in a more disparate manner) are on to something.

I have written before about the beautiful cuttlefish (marine mollusks of the order Sepiida). Cuttlefish are closely related to another order of mollusks, the Sepiolida, or bobtail squid, which are perhaps even more endearing. With huge expressive eyes, tiny little tentacles, and opalescent skin, bobtail squids look like they were designed by a Sanrio artist having a strange day. Sepiolida cephalopods appear to be all head (they are also known as dumpling squid or stubby squid because of this shape)–and their large rounded navigation fins, which stick out like Dumbo’s ears only add to the impression. Members of the Sepiolida do not have cuttlebones but they are far more similar to cuttlefish than to other squid—perhaps their taxonomical classification will change as they are better understood.

There are approximately 70 known species of bobtail squid living in the shallow coastal waters from the Mediterranean, to the Indian Ocean, to the Pacific. To quote the Tree of Life Website, “Members of the Sepiolida are short (mostly 2-8 cm), broad cephalopods with a rounded posterior mantle.” The animals are gifted hunters which eat shrimp, arthropods, and other small animals which they chomp apart with a horny beak at the center of their arms. During the day, bobtail squid bury themselves in the sand with only their eyes protruding and then they hunt at night. Certain species of bobtail squid are known to be poisonous, like the lovely Striped Pyjama Squid (Sepioloidea lineolata). This poison is not well understood and may be contained in the slime produced by the creatures.

Bobtail squid are bioluminescent and they use this ability to disguise their profile when viewed from below–a helpful sort of camouflage which serves them as predators and prevents them from becoming prey. Young bobtail squid are not born with the bioluminescent bacteria but must capture them from the water column in order to start the symbiotic colony within their own bodies. The symbiotic relation between the bobtail squid and the bacterial colony has been much studied in the laboratory.

It was thanks to such studies that scientists first began to understand the method through which bacteria communicate with each other. Called “quorum sensing”, such communication takes place within a group of bacteria by means of signaling molecules. The chemical conversations allow bacteria to respond quickly and in aggregate to changes in their environment (to such a degree that a bobtail squid can tell the bacteria within its own tissues how much to fluoresce and can thereby determine its own luminosity by communicating with millions of living entities inside itself). I have written before about how critical bacteria are to the planet and the Earth’s ecosystem. Studying the bobtail squid provided the first understanding of the way that bacteria communicate with each other, but we are now beginning to suspect that such communication might take place on a vast—perhaps even a global—scale.

I had a post all planned for today but the difference between reality and fancy has forced me to scrap my original idea. First, and by way of overall explanation, allow me to apologize for not writing a post last Friday. I was attending a stamp convention in Baltimore over Labor Day weekend in order to fulfill a social obligation. The stamp convention is where my idea for today’s post came from and, of course it’s also where my idea went wrong.

I had initially (optimistically) planned on selecting a variety of stamps representing categories from my blog. What could be better than a bunch of tiny beautiful pictures of snakes, underworld gods, furry mammals, planetary probes, gothic cathedrals, and so forth? But, alas, my concept was flawed. The international postal industry is vast beyond the telling, and, undoubtedly, some nation on Earth has issued stamps featuring each of those subjects, however stamp collectors do not categorize their collections by subject. Instead they organize their precious stamps by pure obsession (usually but not always centered around a particular historical milieu). Apparently there are also subject stamp collectors out there…but real stamp collectors think of them the way that champion yachtsmen regard oafs on jet skis.

True philatelists are more interested in finding oddities which grow out of historical happenstance. Their great delights are the last stamps issued by an occupied country just before regime change, or the few stamps issued with the sultan’s head upside down, or a stamp canceled by a Turkmenistan post office which was destroyed a week after it was built. The nuances associated with such a subtle field quickly overwhelmed me. Additionally, I was unable to approach gray-haired gentlemen in waistcoats who were shivering in delight from looking at what appeared to be identical stamps with identical potentates and ask if there were any stamps with cuttlefish. It seemed blasphemous. I ended up leaving the stamp show without any stamps at all!

But don’t be afraid. There is an entity which is even more obsessive than the stamp dealers: the internet! To add to my previous post on catfish stamps here is a gallery of mollusk stamps which I found online. The beautiful swirls and dots and stripes of this handful of snails, octopuses, slugs, and bivalves should quickly convince you that even the world’s post offices have nothing on nature when it comes to turning out endless different designs.

When I was a child, my family went to the invertebrate house in Washington, DC. Upon entering the building, there was a very beautiful aquarium which contained the most alien creature I have ever encountered. It was a beautiful glistening red…and then it instantly changed color to bright white with pale dun spots. Next the strange being sank through the water column and changed color and texture. Its smooth skin knotted up into ropey bumps. The speckled white tuned to wavy deep brown lines. Intelligent eyes with W-shaped pupils regarded me from what suddenly seemed to be a hunk of rock. I had encountered my first live cuttlefish. In fact there were two in the tank, as I discovered when a patch of unremarkable sand changed shape and color and jetted to the surface while flashing rainbow colors. They were worked up because they were about to be fed and, when eating their suppers, the cuttlefish put on a particularly good show. They changed color like digital screens and waved their eight arms about and then ZAP! elongated feeding tentacles shot out from under their mantles to grab the anchovies from across the length of the tank. Then they rocketed around with uncanny torpedo speed.

Cuttlefish are cephalopods like octopuses, argonauts, squid, and nautiluses. Across the long ages they have descended from those magnificent nautiloids and othocones who ruled the world during the Ordovician era. Cuttlefish are one of the most intelligent invertebrates: their brains make up a substantial portion of their body mass, and their behavior when hunting, hiding, and courting is complex. The unusually shaped eyes of the cuttlefish are among the finest in the animal kingdom. Their blood makes use of copper rather than iron to fix oxygen so it runs green. All cuttlefish possess poisons in their saliva. In fact the Pfeffer’s Flamboyant Cuttlefish is as toxic as the Blue-ringed octopus.

But why am I talking about these extraordinary mollusks during a week devoted to blogging about color? First of all cuttlefish are “the chameleons of the sea.” As I observed at the zoo, they can change color with a speed and facility unrivaled by any other creature. They use their mastery of color to camouflage themselves, to hunt, and to communicate with each other. The animal’s existence literally hinges around the color-changing chromatophores in their skin. But the association of cuttlefish and color doesn’t stop there. Cuttlefish produce a dense ink which they squirt into the ocean to disguise their movements when frightened. This sepia ink, collected from the ink-sacks of common cuttlefish destined for the table, was prized for writing and for drawing during the classical era. Many of the great histories and literary masterpieces of Greco-Roman thought were first penned in sepia ink. Although other inks took the place of sepia for writing, it maintained its place in the artist’s studio up until the late nineteenth century when it was supplanted by synthetic pigments.

This means that many of the masterpieces of draftsmanship were also created with sepia ink. A particularly effective and pleasing style was to sketch something in watered down sepia washes and finish the details with black india ink. Like chartreuse, magenta, and vermilion, the name sepia itself has become synonymous with a color. This reddish brown is famous in old masters pen-and-ink drawings, antique photos, and memory-hazed movie flashbacks. Not only has this ink provided some of the most beautiful drawings in history, recent studies have shown that cephalopod ink is toxic to certain cells—particularly tumor cells, so we may not have written the last concerning sepia ink.