You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Permian’ tag.

Our Inktober special feature of Halloween-adjacent pen-and-ink drawings continues with this enigmatic golden orchid monastery piece which I drew with colored inks on yellow paper.

Lately I have been drawing a series of intricate altarpiece-style compositions after the style of Medieval illuminators (whose seminal contributions to art, culture, and media have been underappreciated because of the post-Vasari cult of celebrity). Hopefully writing about these illustrations in these posts will help contextualize the themes I am trying to highlight.

Here is a little monastic microcosm of the world. In one monastery, a white-haired abbot lords it over his little flower novices. In a sister monastery, the mother superior and her votaries carefully send out an intimate message to the monks by means of technology. Sundry lizard people, extinct animals, and cloaked figures roam about in the space between the two houses as a rain of yellow orchid blossoms falls down from the heavens.

To my mind, the most important part of this composition is the tiny strip of nature in the foreground–a little ecosystem of weeds, wildflowers, seeds, nemotodes, myriapods, and maggots (who are furiously breaking down a mouse skull). The human world of sly courtships, status posturing, and religious grandstanding grows up out of this substrate and pretends to be superior to it (while actually being entirely dependent on the microscopic cycles of life). All of the pompous & made-up things which humankind uses to dress up our savage primate drives do not change the fact that ecosystems are of paramount importance.

The religions of Abraham (among others) put animals and the natural world at the bottom of their moral hierarchy. I believe they are ultimately doomed because of this stupid outlook. Whether they will take us all to a garbage-strewn grave with them remains an open question.

Last week I finished up the AtlasObscura course on cephalopods, a Zoom mini-survey of this astonishing class of mollusks. The course was a delightful romp through morphology, taxonomy, paleontology, and ecology and featured some virtuous side lessons about how to protect Earth’s ecosphere (and ourselves).

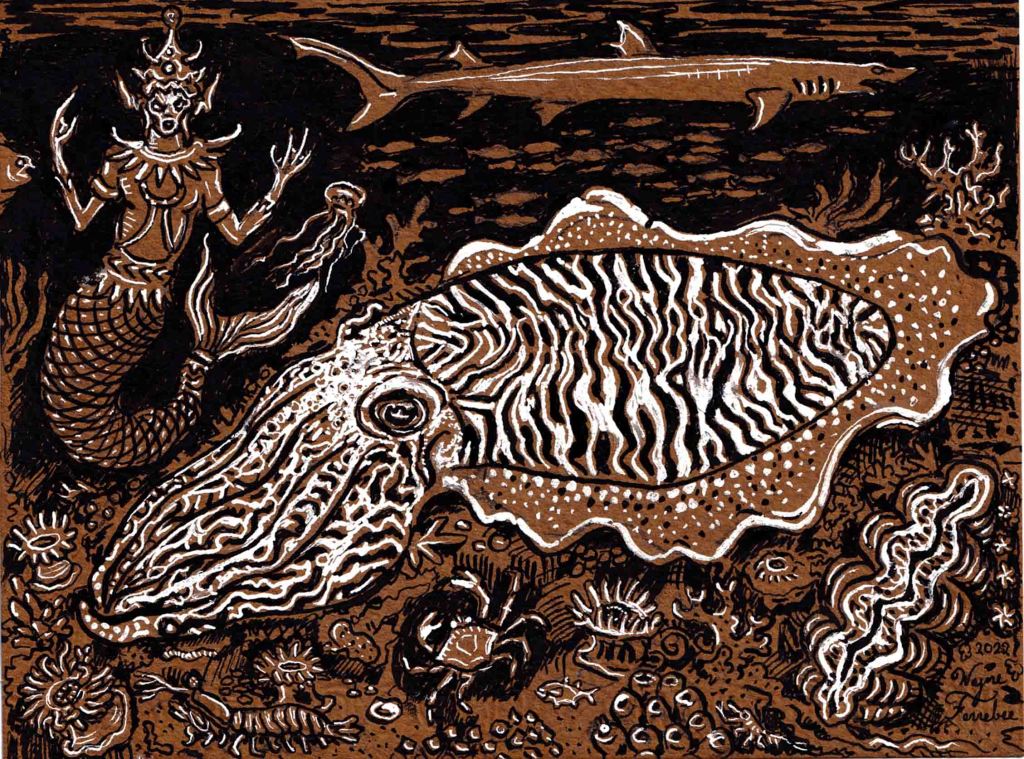

The incredible diversity, beauty, and wonder of cephalopods reminded me that I have not blogged about them…or any molluscs…or anything else for far too long. Ergo, as a promise of more posts to come, here are two little cephalopod drawings I made to share with the class.

The first picture (top) is an Indo-Pacific cuttlefish enjoying the reef and trying to overlook the whimsical Thai/Malay merman who has appeared out of the realm of fantasy (note also the reef shark, giant clam, and mantis shrimp). The second image (as per “homework” instructions) is a cooperoceras flashing iridophores which it may or may not have had as various lower Permian sea creatures (most notably Helicoprian) look on in dazzled envy.

We will talk more about these creatures in weeks to come (and maybe more about the Permian too, since I keep thinking about how the Paleozoic ended), but for now just enjoy the little tentacled faces! Also, it is “inktober” and I have been obsessed with classic pen and ink, so maybe get ready for more drawings as well (to say nothing of our traditional Halloween theme week, which will be coming up quite soon).

During the Permian era (around 300 million years ago) the strange slow dance of Earth’s tectonic plates brought together all the world’s major landmasses into the supercontinent Pangaea. Because of its very nature, Pangaea changed the world’s climate in bizarre ways. Baking hot deserts were so far from the coast that they never received rain. Landlocked seas boiled away and left great evaporitic deposits of strange minerals which we still mine and exploit. Huge mountains rose and fell as the continents crashed together.

Pangaea lasted for approximately 100 million years, during a time of tremendous biological upheaval and diversification. The worst mass extinction in the history of life took place during the continent’s heyday (The Permian-Triassic extinction event took place about 250 million years ago). After the great dying, he first dinosaurs and mammals walked the super continent. However this post is not a meditation concerning Pangaea (thankfully– since its history is extraordinarily complicated).

The idea which excites me is that Pangaea was only a third of the Earth. The remainder of the globe was taken up by water. Between Laurasia and Gondwana there was a great wedge shaped ocean called the Tethys Ocean (indeed Pangaea looked somewhat like Pacman—as you can see on the beautifully illustrated map by Australian freelance illustrator Richard Morden). Named after a titaness who was the daughter of Uranus and Gaia, the Tethys radically changed shape as the continents separated. Through big parts of its history, large parts of the Tethys consisted of warm shallow continental shelves (which are ideal environments for fossil deposits). Paleontologists and Geologists thus know a great deal about the natural history of the Tethys Ocean.

The remainder of the globe was a single world ocean called Panthalassa (or the Panthalassic Ocean). If you looked at Earth from outer space from a particular angle it would have been entirely blue (which is fitting for “Panthalassa” was not named after any god or goddess but from a Greek neologism meaning “universal sea”). The Panthalassa is not so well known as the Tethys. As Pangaea broke apart almost the entire ocean floor was subducted underneath the North American and Eurasian plates. However Geologists sometimes find tiny distorted remnants which were one part of the gigantic world sea.

It is the holiday season and decorated conifers are everywhere. Seeing all of the dressed-up firs and spruces reminds me that Ferrebeekeeper’s tree category has so far betrayed a distinct bias towards angiosperms (flowering plants). Yet the conifers vastly outdate all flowering trees by a vast span of time. The first conifers we have found date to the late Carboniferous period (about 300 million years ago) whereas the first fossils of angiosperms appear in the Cretaceous (about 125 million years ago) although the flowering plants probably originated earlier in the Mesozoic.

The first known conifer trees resembled modern Araucaria trees. They evolved from a (now long-extinct) ancestral gymnosperm tree which could only live in warm swampy conditions—a watery habitat necessitated since these progenitor trees did not cope well with dry conditions and also probably utilized motile sperm. Instead of relying on free-swimming gametes and huge seeds, the newly evolved conifers used wind to carry clouds of pollen through the air and were capable of producing many tiny seeds which could survive drying out. Because the evergreen cone-bearing trees could survive in drier conditions, the early conifers had immense competitive advantages. These advantages were critical to survival as the great warm swamps of the Carboniferous dried out. The continents, which had been separated by shallow oceans and seas, annealed together into the baking dry supercontinent of Permian Pangaea. In the arid deserts and mountains, the conifers were among the only plants which could survive.

This ability to live through any condition helped the conifers get through the greatest mass extinction in life’s history—The Permian–Triassic (P–Tr) extinction event, (known to paleontologists as “the Great Dying”). Thereafter, throughout the Mesozoic they were the dominant land plants (along with cycads and ginkgos which had evolved at about the same time). The Mesozoic saw the greatest diversity of conifers ever—the age of dinosaurs could just as well be called the age of conifers. Huge heard of sauropods grazed on vast swaths of exotic conifers. Beneath these strange sprawling forests, the carnosaurs hunted, the early birds glided through endless green canyons, and the desperate little mammals darted out to grab and hoard the pine nuts of the time.

Although flowering plants rapidly came to prominence towards the end of the Cretaceous and have since become the most diverse plants, today’s conifers are not in any way anachronisms or primitive also-rans. They still out-compete the flowering trees in cold areas and in dry areas. Conifers entirely dominate the boreal forests of Asia, Europe, and North America—arguably the largest continuous ecosystem on the planet except for the pelagic ocean. They form entire strange ecosystems in the Araucaria moist forests of South America—which are relics of the great conifer forests of Antarctica (the southern continent was once a warmer happier place before tectonics and climate shift gradually dragged its inhabitants to frozen death).

The largest trees—the sequoias and redwoods–are conifers. The oldest trees—bristlecone pine trees and clonal Spruces–are conifers (excepting of course the clonal colonies). Conifers are probably the most commercially important trees since they are fast-growing staples of the pulp and the timber industries. Timber companies sometimes buy up hardwood forests, clear cut the valuable native deciduous trees and plant fast growing pines in their place to harvest for pulp. In fact all of the Christmas trees which are everywhere around New York come from a similar farming process. The conifers are nearly everywhere—they have one of the greatest success stories in the history of life. It is no wonder they are the symbol of life surviving through the winter to come back stronger. They have done that time and time again through the darkest and driest winters of the eons.