You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Mammals’ tag.

Do you know what the biggest new trend of 2019 is? It’s QUOKKAS! Finally the ‘teens feature a popular movement that Ferrebeekeeper can get behind.

Quokkas are cat-sized marsupial herbivores of the genus Setonix, a genus which has only a single species Setonix brachyurus. Quokkas are most closely related to kangaroos, wallabies and pademelons: together these animals make up the family known as macropods. Quokkas weigh from 2.5 to 5 kilograms (5.5 to 11 pounds) and live up to 10 years. They have brown grizzled fur and live on a variety of vegetation native to their little corner of southwest Australia. Wikipedia somewhat judgmentally notes that they are promiscuous. Females usually give birth to a sole joey which lives in their pouch for 6 months and remains dependent on the mother for several months beyond that.

Quokka populations have declined precipitously since Europeans colonized Australia. They are outcompeted and preyed on by invasive cats, foxes, and dogs, and they have suffered extensive habitat loss to farms and homebuilding (plus they have some native predators such as snakes). The great Jerusalem for the quokka is Rottnest Island off the coast of Perth. Rottnest means “rat’s nest” in Dutch (which I feel like I could learn!). Apparently the 17th century Dutch explorer, Willem Hesselsz de Vlamingh, spotted extensive colonies of quokkas on the island and mistook the creatures for giant rats.

So why is this dwindling macropod suddenly so popular? Quokkas do not have a particular fear of humans (an exceedingly unwise outlook, in my humble opinion). Additionally, because of the shape of their faces, they seem to have satisfied chilled-out smiles. Indeed, they might actually have chilled-out smiles (they seem pretty benign and happy), but no quokkas returned my phone calls, so I can’t speak to their true emotional state. Anyway, the combined lack of fear of humans and the endearing smiles make them perfect in “selfies” and adorable digital animal photos. The internet is thus good to the quokkas whose popularity is soaring by the day. Perhaps they can parlay this digital fame into population growth and success in the real world (although I suspect the internet’s content-makers would caution the quokka that there is limited correlation between digital and real-world success).

Now that you have read the little essay, here are some adorable grinning quokka pictures. I really hope these guys flourish because just look at them!

Let’s look back through the mists of time to peak at one of the most mysterious and perplexing of mammals, the desmostylians, the only extinct order of marine mammals (although in dark moments I worry that more are soon to follow). Desmostylians were large quadrupeds adapted to life in the water. They had short tails and mighty limbs. Because of this morphology, taxonomists initially thought that they were cousins of proboscideans and sirenians (elephants and manatees), but the fact that their remains have only been found far from Africa (the origin point of elephants, mammoths, mastodons, and manatees & sea cows) along with perplexingly alien traits has caused a rethink of that hypothesis.

(Art by Ray Troll fror SMU)

Extant between the late Oligocene and late Miocene, the desmostylians had powerful tusklike cylindrical teeth and dense heavy bones. The smallest (and oldest) were peccary sized creatures whereas the largest grew to the size of medium whales. It seems like desmostylians lived in littoral parts of the ocean—near coasts and shores where they used their pillar like teeth to graze great kelp forests. They scraped or rasped up the kelp and sucked it down their voracious vacuum maws like spaghetti! It must have been an astonishing sight! My favorite marine paleoartist, Ray Troll has made exquisite pictures of these majestic creatures which help us to visualize them. I really hope they looked this funny and friendly (if they were anything like herbivorous manatees, they probably did!).

(Art by Ray Troll, courtesy SMU)

Speaking of manatees, the gentle sirenians had a hand (or flipper?) in the demise of the poor desmostylians. The dugongs and manatees would never fight anyone or even protect themselves with force—they simply outcompeted the less nimble desmostylians for resources, although one wonders if climate-change and the continuing evolution of different coastal sea plants might also have helped do in the great desmostylians.

The artiodactyls are arguably the most successful order of large land mammals (as long as we don’t mention a dominant lone species of large aggressive primates). Just perusing a list of artiodactyl names reveals how universal and important they are: goats, pigs, cows, giraffes, hippos, sheep, Protoceratidae… wait. What? Among the familiar families of artiodactyls there is an unfamiliar name—an entire vast lineage of hoofed animals completely gone forever. These were the Protoceratidae, hooved animals analogous to their cousins the deer, giraffes, and the camels. The Protoceratidae ranged across North America from the Eocene through the late Pliocene (46 million to 5 million years ago). For 41 million years great herds of these animals grazed the Rocky Mountains, the Great Plains, Appalachia, and Mexico (although the Laramide orogeny was still ongoing as they evolved, and the Great Plains were at first a great forest).

Protoceratidae had complex stomachs for breaking down grasses and other tough vegetation which they grazed upon. Initially the protoceratids were tiny like the smallest deer, but as time progressed some grew to the size of elk. Although the bones in their legs were somewhat different from deer and camels they would have looked similar at a distance…except for a stand-out feature. Male Protoceratidae had a rostral bone—a powerful y-shaped spar of bone jutting from their nose. It is believed that this was a sexual display, meant to impress female Protoceratidae and for sparring with other males for territory and mates (although anybody who has ever been jabbed in the face with a sharpened bone by an elk-size animal would probably testify that the rostral bone could be used defensively). The protoceratids also had a pair of more conventional horns on either side of their head like deer and cattle.

Synthetoceras tricornatus

I wish I could show you more of this extinct family. They lived for a long time and took many shapes and appearances as they spread across the continent into many different niches. A species of particular note was Synthetoceras tricornatus, which was the largest of the protoceratids and which was endemic to most of the continent during the Miocene. Look at how lovely they are. I am ready to move to Texas and start a ranch for them—if they weren’t all dead.

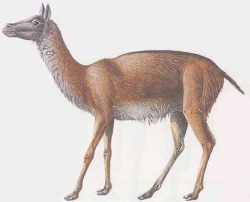

Protoceras

So, what killed off the Protoceratids after 40 million years of success? It seems like they were outcompeted by other, more familiar forms of artiodactyls which developed as the Cenezoic wore on (and which were better suited to vast tracts of grassland—which came to dominate the landscape as the forests died back). The last protoceratid, the Kyptoceras, lived in semi-tropical forests of Florida during the Miocene. Perhaps it was like the Saola, an ever-dwindling wraith that lived deep in the rainforest and was seldom seen until one day it was gone completely. It is an appropriately melancholy picture of the last descendant of a once-great house.

Dusky leaf monkey, Trachypithecus obscurus – Kaeng Krachan National Park, Thailand. Photo by Thai National Parks.

I have been wanting to expand Ferrebeekeeper’s “mammals” categories by writing more about primates…but primates are really close cousins. They are so near to us on the tree of life that it is tricky to write about them. Monkeys and apes venture into the uncanny valley…that uneasy psychological chasm that contains things that are very much like humans, but clearly are not humans.

Therefore, in order to ease us into the subject of primatology, I am going to start with the spectacled langur aka dusky leaf monkey (or, more properly Trachypithecus obscurus). This is a beautiful langur which lives in the dense rainforests of Malaysia, Burma, and Thailand, but realtively little seems to be known about the creatures. Adult male dusky leaf monkeys weighs approximately 8.3 kilograms (18 pounds). Females are somewhat smaller. The monkeys live in troops of about ten or a dozen and they subsist on a variety of tropical fruits and nuts (supplemented perhaps occasionally with other vegetables or small animals). Infants are born orange, but quickly turn dark gray with the distinctive “spectacles” for which the species in known. I don’t really have a great deal of information about these monkeys, but I am blogging about them anyway because they are adorable! Just look at these young langurs. This is exactly the sort of cute introduction which we need to get us started on the topic of primates. We will work on the serious grim monkeys later!

Different fossil plants and animals from the lacustrine deposits of the McAbee Flora of the Eocene (British Columbia, Canada)

Today we return to the long-vanished summer world of the Eocene (the third epoch of the Cenezoic era). During most of the Eocene, there was no polar ice on Earth: a balmy temperate summer held sway from Antarctica to Svalbard. British Colombia was covered by a tropical rainforest where palm trees and cycads contended with warm weather conifers (and with the ancestors of elms, cherries, maples, and alders). Within this warm diverse forest, which thrived between 55 and 50 million years ago, lived numerous strange magnificent birds and insects. Shoals of tropical fish thronged in the acidic foaming waters (which were practically carbonated—since the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels of the Eocene were probably double that of the present). The mammals of this lovely bygone forest were equally splendid–strange proto-carnivores not closely related to today’s mammalian predators, weird lemur analogs, and strange ur-rodents. This week the discovery of two new mammal species was announced. These remarkable fossil finds provide us with an even better picture of the time and place.

a reconstruction of the early Eocene in northern British Columbia: a tapir-like creature (genus Heptodon) with a tiny proto-hedgehog in the foreground. (Julius T. Csotonyi)

One of the two creatures discovered was a tapir-like perissodactyl from the genus Heptodon. The newly discover tapir was probably about the size of a large terrier. I really like tapirs (and their close relatives) but these remains are not a huge surprise–since many perissodactyls thrived in North America during the Eocene. The other fossil which paleontologists found is a surprise—an adorable surprise! Within a stone within a coal seam was a tiny jaw the size of a fingernail. Such a fossil would have been all but impossible to study in the past, but the paleontological team led by David Greenwood, sent the little fossil to be scanned by a CT scanner and then imaged with a 3D scanner. The tiny jaw was from a diminutive hedgehog relative since named Silvacola acares. The little hedgehog grew to a maximum adult size of about 6 cm (2.3 inches) long or approximately thumb-sized. Since it probably lacked spines, this miniature hedgehog was a bit different than the modern hedgehog, but it was definitely a relative.

As discussed in previous posts, I like to imagine the balmy Eocene, when so many mammals which are now the mainstay of our familiar Holocene/Anthropocene world got their first start. It makes it even better to imagine that the thickets were filled with endearing hedgehogs the size of bumble bees.

Camelids are believed to have originated in North America. From there they spread down into South America (after a land bridge connected the continents) where they are represented by llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Ancient camels also left North America via land bridge to Asia. The dromedary and Bactrian camels are descended from the creatures which wandered into Beringia and then into the great arid plains of Asia. Yet in their native North America, the camelids have all died out. This strikes me as a great pity because North America’s camels were amazing and diverse!

At least seven genera of camels are known to have flourished across the continent in the era between Eocene and the early Holocene (a 40 million year history). The abstract of Jessica Harrison’s excitingly titled “Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America” gives a rough overview of these huge extinct beasts:

Aepycamelus was the first camel to achieve giant size and is the only one not in the subfamily Camelinae. Blancocamelus and Camelops are in the tribe Lamini, and the remaining giant camels Megatylopus, Titanotylopus, Megacamelus, Gigantocamelus, and Camelus are in the tribe Camelini.

That’s a lot of camels–and some of them were pretty crazy (and it only counts the large ones—many smaller genera proliferated across different habitats). Gigantocamelus (as one might imagine) was a behemoth weighing as much as 2,485.6 kg (5,500 lb). Aepycamelus had an elongated neck like that of a giraffe and the top of its head was 3 metres (9.8 ft) from the ground. Earlier, in the Eocene, tiny delicate camels the size of rabbits lived alongside the graceful little dawn horses. This bestiary of exotic camels received a new addition this week when paleontologists working on Ellesmere Island (in Canada’s northernmost territory, Nunavut) discovered the remains of a giant arctic camel that lived 3.5 million years ago. Based on the mummified femurs which were unearthed at the dig, the polar camel was about 30 percent larger than today’s camels. The arctic region of 3.5 million years ago was a different habitat from the icy lichen-strewn wasteland of today. The newly discovered camels probably lived in boreal forests (rather in the manner of contemporary moose) where they were surrounded by ancient horses, deer, bears and even arctic frogs! Testing of collagen in the remains has revealed that the camels are closely related to the Arabian camels of today, so these arctic camels (or camels like them) were among the invaders who left the Americas for Asia.

The bones are a reminder of how different the fauna used to be in North America. When you look out over the empty, empty great plains, remember they are not as they should be. All sorts of camels should be running around. Unfortunately the ones that did not leave for Asia and South America were all killed by the grinding ice ages, the fell hand of man, or by unknown factors.

The crabeater seal (Lobodon carcinophagus) is a pale-colored seal which lives on the pack ice around Antarctica. Adult crabeater seals have an average length of 2.3 meters (7 and-a-half feet) and weigh around 200 kg (440 pounds) however the largest male crabeater seals can weigh up to 300 kg (660 lb). The seals’ mass alters considerably over the course of a season as they gorge themselves in preparation for lean times (or—in the case of mothers—for nursing). Like other Antarctica seals, crabeater seals have slender bodies and long snouts. They are gifted swimmers—a talent which allows them to escape their two main predators, killer whales and leopard seals. They infrequently venture beyond the continental shelves of Antarctica (although very rarely one is spotted at New Zealand, Patagonia, or South Africa). They hunt along the pack ice and travel far inland to give birth. The seals give birth to one pup annually and they can live up to 40 years.

Crabeater seals can slither over land fairly well and they range farther onto continental Antarctica than any other indigenous mammal. Crabeater seal carcasses have been found up to 100 kilometers from the coast. So crabeater seals have whole swaths Antarctica to themselves (well aside from big weird penguins, lichens, and Norwegian explorers). Although they may theoretically eat a crab every now and then, the seals are misnamed. Their main prey is Antarctic krill, which they eat in huge quantities (as an aside, Antarctic krill is believed to have the greatest biomass of any single species on Earth). Although they do not have baleen like the great rorquals, crabeater seals have specialized krill-filtering cusps on their teeth which trap the krill and allow water to escape. When krill are not available, the seals can also feed on fish and squid.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about crabeater seals is their sheer numbers. Other than humans (and our livestock) they are the most numerous large mammals on the planet. Caribou and wildebeests exist in herds of hundreds of thousands, but the crabeater seal population numbers in the millions. The full population of crabeater seals is unknown. Estimates range from 7 million to 70 million. Since they are pale colored seals darting between the crushing pack ice of an uninhabited continent we have a population estimate which is off by a factor of ten. The fact that so few people have seen them might explain why they are still so successful.

There are entire species of large mammals living today on Earth which have never been seen alive by humans. Even though they can grow larger than elephants, their numbers and habits are unknown. We might not even know all extant species in the family. These mystery mammals are the beaked whales (family Ziphiidae) masters of deep ocean diving. The family is comprised of at least 21 different species, only 3 of which are well known (thanks to whale hunting in previous centuries). Beaked whales are poorly understood because they are rarely on the surface of the ocean where we can observe them. They are capable of diving more than 1,899 meters (6,230 feet) and can stay underwater for almost an hour and a half. Beaked whales live in the black–down among the underwater seamounts, canyons, and abyssal plains. We only know them from the examination of dead specimens: indeed, for some species of beaked whales that is quite literally true and they have only been seen when dead.

Beaked whales grow to sizes of 4 to 13 metres (13 to 43 ft) depending on the species. They are sexually dimorphic—the males are a different size than the females. Additionally male whales have prominent domed foreheads and a pair of fighting teeth for dueling and sexual display (these teeth do not fully develop in females). Beaked whales feed on squid, and, to a lesser extent, fishes and invertebrates which they capture from the ocean bottom by means of suction. In order to produce this suction effect, the whales have highly nimble tongues and throat grooves.

The most distinctive features of beaked whales (save perhaps from their rostral “beaks”) are the body features which allow them to dive so deeply and then hunt in the dark crushing waters. The lungs of beaked whales collapse at a certain pressure—most likely as a way to minimize the dangers of nitrogen transfer. Their livers and spleens are huge in order to deal with the dangerous metabolic bi-products of prolonged periods when they are unable to breathe. Additionally, their blood and muscle tissue is capable of capturing and storing substantially greater quantities of oxygen than the tissue of other mammals. Beaked whales can pull their pectoral flippers into grooves which run along the sides of their bodies and thus become more streamlined.

In order to find their way in the deep ocean, the whales rely on sophisticated acoustic echo-location organs. Lips behind the blowhole produce high pitched vibrations which bounce off of prey and obstacles. Echoes from these vibrations are then picked up and focused into the whales’ sensory organs by special fat deposits and bone structures. Unfortunately this method of echolocation seems to make beaked whales extremely sensitive to sonar. Resurfacing whales are unable to avoid the amplified sound waves and can suffer injuries to their sensory organs (or even to their large delicate livers). Additionally, it is theorized that Beaked whales may try to resurface too quickly to avoid sonar and therefore risk decompression sickness.

Humankind has also been fishing ever deeper waters as fish stocks crash—which involves the whales in by-catch issues. Hopefully we will learn more about this family of enigmatic divers (and become more responsible stewards of the ocean) so that the beaked whales do not vanish before we even get to know them.