You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Greco-Roman’ tag.

This is the guardian god Tutu. Tutu is a god from the later period of Ancient Egyptian culture (indeed, the statue above may come from the Greco-Roman era…or even the Byzantine era of Egypt). Tutu was a son of the mysterious and dangerous goddess Neith (a creator goddess from outer darkness) but he was more familiar and comforting than Neith: Egyptians thought of Tutu as a god who protected mortals from Neith’s other more dangerous children–demons and nightmares from the world of darkness. Originally Tutu was a protector of tombs, but over the centuries he morphed into a guardian of sleep who protected slumbering commoners from nightmares. I really like this statue because he seems like a friendly (but maybe slightly silly) dream guardian. Although he has a cat’s body, his elongated torso makes me think of a dachshund and his pudgy hangdog face reminds me of Rodney Dangerfield or some such sadsack comedian. Let’s not even talk about the scorpions on his feet!

But I guess any protection from nightmares is better than none, and Tutu was popular in his day, during the twilight fadeout of Egypt’s ancient gods.

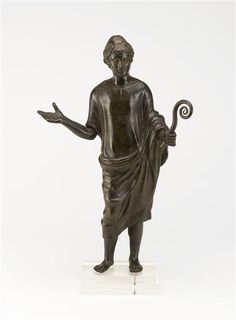

One of the most popular and instantly recognized symbols of classical antiquity did not make it through the millennia. The lituus was a spiral wand which looked a bit like a bishops crozier which was the symbol of augurs, diviners, and oracles in the Roman world. If you waved one around today, people would think it was an obscure prop from PeeWee’s Playhouse or a messed-up art student’s idea of a fern frond. Yet the lituus was everywhere in ancient Rome—it was on murals, and carved in statuary, and on the money. Musicians even developed a great brass trumpet to look like the sacred symbol (or possibly it was the other way around—the Etruscans had a war-trumpet which looked a great deal like the littuus and possibly gave its name to the scrying instrument).

Whatever the history and etymology, the Romans of the Republic and the Empire loved the lituus–and the whole world of divination, magical prophecies, and mystical portents which it represented. The littuus itself was seemingly used to mark a section of the sky to the eye of the interpreter of signs. Whatever birds flew through this quadrant represented what was to come. Obviously, there was just as much fraud, skullduggery, and flimflam in Roman divination as there is in modern tealeaves, horoscopes, tarot, and other such bollocks—but at least the Roman art had the grace of the natural worlds (as well as the raw violence which was stock and trade of all aspects of society in the ancient world).

Of course, it could be argued that the lituus isn’t quite as fully vanished as I have made it out to be. Scholars of comparative religion see the same shape in the Bishop’s curling crozier (bishops seem to have stolen the hats of Egyptian priests as well). To my eye the shape looks like a question mark, and has a similar meaning. I wonder where question marks came from.

(Crozier from Northern Italy in the early 14th century, bone and paint)

Musicians also owe fealty to the lituus, both as a symbol of otherworldly arcane spirit-knowledge and as a sort of ancient brass instrument. Modern horns evolved, to a degree, from the lituus and I wonder if it found its way into the “fiddle heads of rebecs and violins (although I am not going to research those connections today). Whatever the case, it is a lovely and interesting symbol for a branch of magical thought which the Romans held extremely dear and it is worth knowing by site if you plan on casting an eye on the ancient Mediterranean world.

When I was a child, my family went to the invertebrate house in Washington, DC. Upon entering the building, there was a very beautiful aquarium which contained the most alien creature I have ever encountered. It was a beautiful glistening red…and then it instantly changed color to bright white with pale dun spots. Next the strange being sank through the water column and changed color and texture. Its smooth skin knotted up into ropey bumps. The speckled white tuned to wavy deep brown lines. Intelligent eyes with W-shaped pupils regarded me from what suddenly seemed to be a hunk of rock. I had encountered my first live cuttlefish. In fact there were two in the tank, as I discovered when a patch of unremarkable sand changed shape and color and jetted to the surface while flashing rainbow colors. They were worked up because they were about to be fed and, when eating their suppers, the cuttlefish put on a particularly good show. They changed color like digital screens and waved their eight arms about and then ZAP! elongated feeding tentacles shot out from under their mantles to grab the anchovies from across the length of the tank. Then they rocketed around with uncanny torpedo speed.

Cuttlefish are cephalopods like octopuses, argonauts, squid, and nautiluses. Across the long ages they have descended from those magnificent nautiloids and othocones who ruled the world during the Ordovician era. Cuttlefish are one of the most intelligent invertebrates: their brains make up a substantial portion of their body mass, and their behavior when hunting, hiding, and courting is complex. The unusually shaped eyes of the cuttlefish are among the finest in the animal kingdom. Their blood makes use of copper rather than iron to fix oxygen so it runs green. All cuttlefish possess poisons in their saliva. In fact the Pfeffer’s Flamboyant Cuttlefish is as toxic as the Blue-ringed octopus.

But why am I talking about these extraordinary mollusks during a week devoted to blogging about color? First of all cuttlefish are “the chameleons of the sea.” As I observed at the zoo, they can change color with a speed and facility unrivaled by any other creature. They use their mastery of color to camouflage themselves, to hunt, and to communicate with each other. The animal’s existence literally hinges around the color-changing chromatophores in their skin. But the association of cuttlefish and color doesn’t stop there. Cuttlefish produce a dense ink which they squirt into the ocean to disguise their movements when frightened. This sepia ink, collected from the ink-sacks of common cuttlefish destined for the table, was prized for writing and for drawing during the classical era. Many of the great histories and literary masterpieces of Greco-Roman thought were first penned in sepia ink. Although other inks took the place of sepia for writing, it maintained its place in the artist’s studio up until the late nineteenth century when it was supplanted by synthetic pigments.

This means that many of the masterpieces of draftsmanship were also created with sepia ink. A particularly effective and pleasing style was to sketch something in watered down sepia washes and finish the details with black india ink. Like chartreuse, magenta, and vermilion, the name sepia itself has become synonymous with a color. This reddish brown is famous in old masters pen-and-ink drawings, antique photos, and memory-hazed movie flashbacks. Not only has this ink provided some of the most beautiful drawings in history, recent studies have shown that cephalopod ink is toxic to certain cells—particularly tumor cells, so we may not have written the last concerning sepia ink.