You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘symbolism’ tag.

This is the flag of Madagascar: three rectangles of white, red, and green. The rectangles are nearly equal in size (although the vertical white rectangle is slightly wider). The flag has been the symbol of Madagascar since 1958—which means it was adopted two years before the island nation became independent of the French empire in 1960.

Madagascar is an ancient island subcontinent which is currently located in the Indian Ocean just east of Sub Saharan Africa (it has actually moved around a great deal during geological history–but that is irrelevant for a post about the national flag). The large island was colonized by two waves of human inhabitants. The first Madagascar people were Austronesians who arrived between 350 BC and 550 AD via boat from the island of Borneo. Boneo and Madagascar are about 7,600 kilometers (4760 miles) apart, so this was no trifling feat of navigation! The second main wave of human colonization took place around 1000 AD, when many Bantu people crossed the Mozambique channel–which is a more manageable boat journey of 460 km (286 miles).

Madagascar is an ancient island subcontinent which is currently located in the Indian Ocean just east of Sub Saharan Africa (it has actually moved around a great deal during geological history–but that is irrelevant for a post about the national flag). The large island was colonized by two waves of human inhabitants. The first Madagascar people were Austronesians who arrived between 350 BC and 550 AD via boat from the island of Borneo. Boneo and Madagascar are about 7,600 kilometers (4760 miles) apart, so this was no trifling feat of navigation! The second main wave of human colonization took place around 1000 AD, when many Bantu people crossed the Mozambique channel–which is a more manageable boat journey of 460 km (286 miles).

The red and the white of the Madagascar flag are said to represent both the Merina kingdom (which fell to the French in 1896) and the colors of the flag of Indonesia (red and white) which was where the first Madagascar people hailed from. The Merina people are highlanders who culturally dominated the island for centuries.

The green of the flag is said to represent the Hova people—the free peasantry. During the Merina kingdom, society was divided into three classes: Merina aristocrats, Hova peasants, and slaves (coincidentally these slaves were obtained from raids on the Makua people during the 19th century). The Hova apparently played a large part in the 1950s independence movement against the French colonial authorities.

In conclusion, the more I have studied the Madagascar flag, the less sure I am that it means anything. I feel like some graphically inclined revolutionary might have made up the whole thing in 1958 because he liked the colors. More importantly however, I have become fascinated by the strange human history of this perplexing mini continent which was inhabited so very recently.

In conclusion, the more I have studied the Madagascar flag, the less sure I am that it means anything. I feel like some graphically inclined revolutionary might have made up the whole thing in 1958 because he liked the colors. More importantly however, I have become fascinated by the strange human history of this perplexing mini continent which was inhabited so very recently.

Chinese opera traces its roots back to the Three Kingdoms period (or even earlier). The first formal opera troop is said to have been founded by Emperor Xuanzong who ruled China from 712 AD to 756 AD, a period which marked the apex of the Tang Dynasty. This first opera troop styled itself as “the Pear Garden” and even today Chinese opera performers describe themselves as “Disciples of the Pear Garden.”

Styles and performing conventions have changed many times in the long history of the opera as different forms have come and gone. The craft is based on mimetic gestures which express narrative actions such as horse-riding, fighting, or traveling by boat. Traditional instruments such as lutes and gongs provide a score: the libretto is sometimes sung and sometimes recited.

The most visually arresting features of Chinese opera are the bold & colorful masks worn by the performers. These masks hearken back to an ancient tradition of face-painting among warriors and, as with war paint, the colors and patterns bear symbolic meanings. The spirit and personality of each character is effectively color coded. Wikipedia nicely summarizes the meaning of each color of mask with the following handy chart (which I have copied verbatim):

White: sinister, evil, crafty, treacherous, and suspicious. Anyone wearing a white mask is usually the villain.

Green: impulsive, violent, no self restraint or self control.

Red: brave, loyal.

Black: rough, fierce, or impartial.

Yellow: ambitious, fierce, cool-headed.

Blue: steadfast, someone who is loyal and sticks to one side no matter what.

Additionally gold and silver faces represent mystery and aloofness. Of course the masks are often not real masks on stage but elaborate make-up and costuming so that the players can sing and pantomime to extravagant and wondrous effect (and so that patrons can appreciate pretty faces).

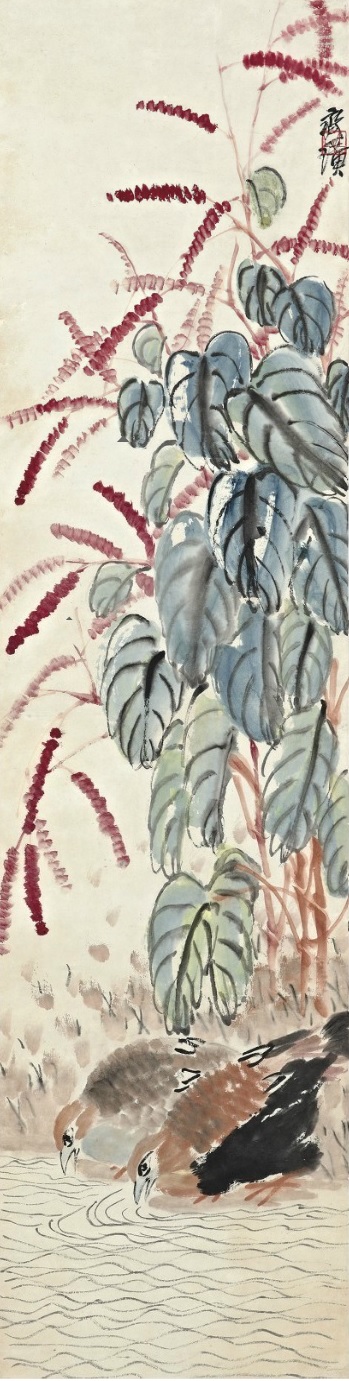

Quail are mid-sized members of the Galliformes (the gamebirds) which live around the world, usually staying close to the ground where they hide among the undergrowth and peck out a living eating small invertebrates, seeds, and berries. Multiple species of the quail genus Coturnix live in China, where they have long been a favorite of hunters, poultry farmers, gamblers, and, of course, artists. Quail were associated with autumn and they form the centerpiece of several lovely scrolls and small compositions about the plants and flowers of fall. The birds also are utilized as a symbol of bravery (since a certain element of Chinese society fought male quail in battles reminiscent of cockfights and bet on the winner). The painting at the top of this post also utilizes the quail as a symbol, albeit in a way which is extremely obscure to non-Chinese speakers. The Chinese phrase for 5 quail is “wu anchun”–and the first two syllables “wu an” are a homonym for “no peace” (in China, a land which frequently knows censorship, homonyms are an indirect way of making political of social comments). The painting above was thus a plangent comment on the fall of the Sung dynasty in the mid-13th century (which felt like a dark autumn to the Chinese literati). Fortunately the following quail paintings are not quite so somber in tone, but convey instead the beauties of autumn or the simple delight the artists took in the endearing rounded form of the wild quail.

On the Christian Liturgical calendar, yesterday was Palm Sunday—the day Christ entered Jerusalem for the week of the passion. Here is one of my favorite religious paintings depicting Jesus saying farewell to his mother before leaving for Jerusalem (and for his death). The painting was completed by Lorenzo Lotto in 1521 and it reflects what is best about that eccentric northern Italian artist.

In many ways Lotto was a kind of shadowy opposite to Titian, who was the dominant Venetian artist of the era. Whereas Titian remained in Venice, Lotto studied in the city of canals but then moved restlessly from place to place in Italy. Titian was the height of artistic fashion throughout the entirety of his life (and, indeed, afterwards) while Lotto fell from popularity at the end of his career and his work then spent long eras in obscurity. Titian’s figures seem godlike and aloof: Lotto’s are anxious and human, riddled with doubts and fears.

Yet there is something profoundly moving in the nervous and unhappy way that Lotto paints. The jarring acidic colors always seem to highlight the otherworldly nature of the Saints and Apostles. Everything else, however points to their humanity. The figures imperceptibly writhe and squirm away from the hallowed norm (and toward mannerism). Instead of a glowing sky here is a dark roof with a globe-like sphere cut into it. The perspective lines do not lead to heaven or a glittering temple but rather to an obscure cave-like topiary within a fenced garden. Only Christ is serene as he bows to his distraught mother, yet he too seems filled with solemn sadness.

A remarkable aspect of this painting is found in the ambiguous animals located in the foreground, midground, and distance. In the front of the painting a little alien lapdog with hypercephalic forehead watches the drama (from the lap of painting’s donor, richly dressed in Caput Mortuum). A cat made of shadow and glowing eyes moves through the darkened columns of the façade. Most evocatively of all, two white rabbits are the lone inhabitants of the periphery of the painting. They scamper off towards the empty ornamental maze. The animals all seem to have symbolic meaning: the dog stands for loyalty, the cat for pride, and the rabbits for purity–but they also seem like real animals caught in a surreal & gloomy loggia. The living creatures might be party to a sacred moment but they are also filled with the quotidian concerns of life, just as the apostles and even the virgin seem to be moved by the comprehensible emotional concerns of humanity. Lotto never gives us Titian’s divine certainty, instead we are left with human doubt and weary perseverance.

Famous in love stories and movies, the Claddagh ring is a traditional Irish band with elements that go back to Roman times. The ring consists of two hands holding a crowned heart and dates back to the 17th century where the design originated in the village of Claddagh by Galway.

According to tradition, each element of the ring is symbolic. The hands stand for friendship, the heart stands for love, and the crown stands for loyalty. The position of the ring on the hands is also important: when the ring is on the right ring finger with the heart out, it means the wearer is single and seeking love (or some reasonable approximation); when the ring is on the right hand with the heart turned in, it means the wearer is in a relationship, but not engaged. When the Claddagh ring jumps to the left ring finger things have gotten serious: the Claddagh with the heart outward indicates betrothal and when heart is turned inward, the wearer is married. Or at least that is what people say about the tradition. Every ring I have worn ceaselessly turned like a record on my finger. I’m sure all sorts of couples would end up in desperate needless fights if the Claddagh tradition was held too closely.

Although the folklore traditions in the paragraph above seem to be innovations of the nineteenth century, the ring descends (through a long lineage) from Roman “fede” rings which featured clasped or joined hands as symbolic of a sacred vow.

This past April, I announced with some fanfare (or at least with bold letters) that Ferrebeekeeper was going to expand to feature a digital gallery of my paintings and other artworks. In retrospect, perhaps I should not have made that statement on April Fool’s Day (although that is the day I started blogging). Circumstances have indeed made a fool of me, and my projected site expansion has been delayed again and again. More than a season has gone by and still there is no art gallery. Fortunately, I am now confident that my gallery launch really is just around the corner! To give you a little teaser until the final version is launched, here are two of my miniature allegorical paintings from a series which I started more than a year ago.

Here’s the story behind the genesis of these works: when I was cleaning my pockets before doing a load of laundry I found a sketch of a centaur, a clock, and a snail trapped in a miniature torus-shaped universe. Although I’m not sure what prompted that initial sketch, I have since made several tiny paintings based around toruses which, as explained here are elegant metaphors for insular universes. Indeed some cosmologists and topologists feel that the actual universe might well be torus-shaped (or more precisely, shaped like a triple torus) an idea which appeals to my inner gourmand. The paintings are obviously echoes of each other. Both feature huge predatory animals lurking under pastries floating in outer space. The splendid toadfish (Sanopus splendidus) in the first painting and the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) in the second are even facing the same way as if both waiting in ambush. Each panel also has an invertebrate, a galactic backdrop, and ancient beings brandishing hand weapons. However the cast and the props are quite different–a bold Assyrian warrior takes the place of the desiccated mummy while the gothic clock sunk in icing is replaced by a mournful bagpipe floating in space. A yellow lipped sea krait seems intent on escaping the entire scene.

What does all of this mean? Well, as Socrates surmised, artists don’t know what their works mean. Like everyone else we have to guess, but the reoccurrence of similar roles in the two paintings—even as the setting and the circumstances change–suggest to me the circular nature of interaction between living things. This theme is highlighted by the circular nature of the main subject, the torus. And of course there is something obviously and purposefully missing from both paintings, a physical and metaphysical emptiness exemplified by the famous hole in the donut, and the void of the universe. Whether this additionally reflects the hunger of the animals, the soundlessness of the bagpipe, the lifelessness of the mummy, and the timelessness of the stopped clock is an open question.