You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘hunt’ tag.

Behold, the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox), the top predator of Madagascar (exempting, as always, our own very predatory kind). The fossa weighs between 5.5 and 8.5 kg (12 to 20 pounds) and lives mostly on primates—namely the lemurs which are everywhere indigenous to the strange micro-continent. Since lemurs are brilliant climbers, the fossa is also an arboreal specialist and it can run down trees headfirst and execute stunning acrobatic leaps which would make a trapeze artist blanche and retire. The predator prefers hunting lemurs but it also dines on bats, reptiles, tenrecs, rodents, birds, and whatever other small living creatures it can catch.

The first time I saw footage of a fossa, my mind kept insisting it was a cat…no a weasel…no a stretched-out bear. Its extreme similarity to familiar predators combines in a sinister way with its lithe alien movements to make it seem very peculiar. I wonder too if some desperate little tree-creature part of our brain doesn’t respond badly to the fossa-for it is difficult to look away from one in action, and it has many similarities with analogous predators encountered by our arboreal forbears. It hunts both by day and night. It climbs, swims, runs, and lurks with great skill–so there is never any true safety for animals which it preys on.

According to taxonomy and genetics, the fossa is indeed closely related to cats, bears, weasels, seals, and all of the other members of the order Carnivora. The fossa is perhaps most closely related to viverrids (the civets and genets), but it shares many features with felines as well, and may be considered to be descended from an intermediary form. The ancestor of the fossa first came to Madagascar around 20 million years ago, during the Miocene as forests dwindled and grasslands spread on Africa and as Madagascar drifted particularly close to the great continent.

Fossas live to around twenty years of age. They have social lives similar to cats, and even have similar vocalizations. Fossas of both genders have bizarre elongated external genitals (and the male member is equipped with backwards pointing spines). Additionally, they secrete an orange substance which “colors their underparts”. You can go look up details and pictures on your own time. The mother fossa gives birth to litters of two to four (though occasionally as few as one or as many as six) cubs, which mature slowly. Physical maturity is not reached until the age of two and the young fossa do not reproduce until a year or two after that. Fossa have always been solitary and rare, but human habitat-destruction (among other ills) seems to be making them even scarcer.

I started writing this post imagining that the fossa would be esoteric and largely unknown to most of my readers, but the internet quickly revealed that it is a film star and a media darling of our age. Apparently a fossa was the villain of “Madagascar” an animated children’s film about lemur society and a zoo-breakout. How did I miss an animated movie about lemurs? I’m going to go watch that right now.

In Celtic mythology, there is a mysterious group of supernatural beings, the aes sídhe, who belong to a realm which is beyond human understanding (yet which lies athwart the mortal world). The greatest among these aes sidhe were gods and goddesses—divine incarnations of nature, time, or other abstract concepts. Other members of the fairy host were thought of as elves, goblins, sprites, or imps (for example, the leprechauns–the disconcerting little tricksters of fairydom). However the supernatural world was also filled with the restless dead…beings who were once mortal but whose failures and miseries in life kept them connected to this plain of existence. A particularly ominous group of these dark spirits comprised the sluagh sidhe—the airborne horde of cursed, evil, or restless dead.

In Celtic mythology, there is a mysterious group of supernatural beings, the aes sídhe, who belong to a realm which is beyond human understanding (yet which lies athwart the mortal world). The greatest among these aes sidhe were gods and goddesses—divine incarnations of nature, time, or other abstract concepts. Other members of the fairy host were thought of as elves, goblins, sprites, or imps (for example, the leprechauns–the disconcerting little tricksters of fairydom). However the supernatural world was also filled with the restless dead…beings who were once mortal but whose failures and miseries in life kept them connected to this plain of existence. A particularly ominous group of these dark spirits comprised the sluagh sidhe—the airborne horde of cursed, evil, or restless dead.

The sluagh sidhe (also known simply as the sluagh) were beings who were cursed to never know the afterlife. Neither heaven nor hell wanted them. Like Jack O’Lantern they were condemned to roam the gray world. Unlike Jack O’Lantern, however, the sluagh were reckoned to be a malicious and deadly force. They appeared en masse in the darkest nights and filled the air like terrible rushing starlings or living mist. One of the most horrible aspects of the sluagh was the extent to which their horde existence erased all individual personality (like eusocial insects—but evil and spooky).

The sluagh sidhe (also known simply as the sluagh) were beings who were cursed to never know the afterlife. Neither heaven nor hell wanted them. Like Jack O’Lantern they were condemned to roam the gray world. Unlike Jack O’Lantern, however, the sluagh were reckoned to be a malicious and deadly force. They appeared en masse in the darkest nights and filled the air like terrible rushing starlings or living mist. One of the most horrible aspects of the sluagh was the extent to which their horde existence erased all individual personality (like eusocial insects—but evil and spooky).

Before the advent of Christianity in Ireland, Scotland, and the northlands, the sluagh were thought of as a dreadful, otherworldly aspect of the wild hunt. When the dark gods came forth to course the world with hell hounds, the sluagh were the evil demons and fallen fairies which flew along beside the grim host. After Christian missionaries began to arrive, the idea of losing one’s soul forever became worse than the idea of merely being torn apart by dark monsters—and the sluagh was reimagined as a force which hunted and devoured spirits.

Before the advent of Christianity in Ireland, Scotland, and the northlands, the sluagh were thought of as a dreadful, otherworldly aspect of the wild hunt. When the dark gods came forth to course the world with hell hounds, the sluagh were the evil demons and fallen fairies which flew along beside the grim host. After Christian missionaries began to arrive, the idea of losing one’s soul forever became worse than the idea of merely being torn apart by dark monsters—and the sluagh was reimagined as a force which hunted and devoured spirits.

The sluagh were thought to fly from the west. They were particularly dangerous to people alone in wastelands at night (which sounds dangerous anyway) and to people on the threshold of death [ed.–that sounds dangerous too]. Some of the Irish death taboos against western windows and western rooms are thought to be related to fear of this demonic horde. Although the sluagh could apparently be dangerous to healthy people in good spirits, they seem to have been most dangerous to the depressed, the anxious, and the sick. From my modern vantage in a warm well-lit (northerly-facing) room, the idea of the sluagh seems to be an apt metaphor for depression, despair, and fear. Hopefully they will stay far from all of us!

In Greek mythology, King Oeneus of Calydon was one of the great mortal heroes of his day. Just as Demeter had taught Triptolemus the secrets of growing grain, Dionysus himself taught Oeneus the secrets of unsurpassed winemaking. The merry monarch brought grape culture and the vintner’s arts to all of Aetolia and he grew rich and beloved because of his teaching and his greatness at making wine. To this day “oenophiles” are people who love wine.

The monarch was even luckier in his family. He was married to Althea, a granddaughter of the gods who was said to be nearly as beautiful as her sister Leda, who drew the eye of Zeus himself. He had many sons and daughters: Deianeira (who wed Heracles), Meleager, Toxeus, Clymenus, Periphas, Agelaus, Thyreus (or Phereus or Pheres), Gorge, Eurymede, Mothone, Perimede and Melanippe. But of all these Oeneus’ eldest son Meleager stood out as the greatest hero of his era—a peerless spearman and warrior.

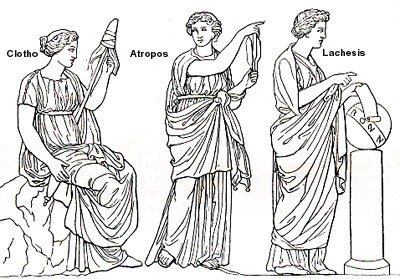

Meleager had nearly died in infancy. His mother Althea was spinning flax when she heard the three fates—the ancient and alien goddesses of all destiny– discussing the baby boy. Old Atropos had pulled out her scissors and was saying that as soon as the brand burning in the fireplace was consumed, the child’s life would end. Althea threw away her weaving and grabbed the blazing log out of fire. She smothered the blaze and hid the log away in a huge locked coffer. Thus Meleager grew into magnificent manhood.

King Oeneus loved the gods and he sacrificed generously to them, but he loved his wine and he drank generously too. One year as he sacrificed to the Olympians he forgot to sacrifice to Artemis, the goddess of the hunt (who was not foremost on his mind anyway since he was a farmer and a wine maker). Alas, it was a terrible error. In her wrath the virgin huntress summoned the Calydonian boar, a descendant of the Crommyonian sow (which in turn was descended from Echidna herself). The immense boar ravaged the countryside. His tusks were huge like trees but sharp like razors and he impaled scores of Calydonian farmers along with their wives and children. He tore up the fields and ate the grape vines. The Corynthians huddled in their walled city and began to starve to death.

Oeneus sent Meleager out to gather the greatest heroes of the era for an epoch hunt and the spearman returned with the foremost fighting men of Greece. He also returned with a woman, the virgin Atalanta, who was beloved of Artemis and had been raised by she-bears. Atalanta could run faster and shoot better than any of her male peers. Her strength and beauty did not go unnoticed by Meleager, who began to pay court to her.

The hunt for the Calydonian boar was terrifying and bloody. Many heroes died under the creature’s iron hooves or upon its evil tusks. However, at last Atalanta shot a perfect arrow into a vulnerable spot in its bronze-like hide. Meleager followed up on the advantage and slew the great pig with his spear. Later, at the drunken feast, he presented the creature’s hide to Atalanta and he was on the verge of begging for her hand when his uncle and brother started a quarrel.

Meleager and the Calydonian Boar. Marble, Roman copy from the Imperial Era (ca. 150 AD) after a Greek original from the 4th century BC.

Arrogant and drunken, Meleager’s kinmen asserted that no virtuous woman would be hunting with men and that the shot was lucky anyway. Since everyone was drinking heavily of Oeneus’ fine wine (and since the guests were heavily armed) the quarrel flew out of control and, in the subsequent melee, Meleager slew both his own brother and his mother’s brother. In fury Althea rushed to her chambers and ripped the charred wood from its coffer. She ran back to the roaring bonfire where all the hunters and revelers were still stunned and hurled the brand into the fire where it was burned away in a moment leaving Meleander dead.

Thus was Artemis avenged on King Wine Man for slighting her in worship.

Kindly accept my apologies for the lack of posts on Thanksgiving week: I was hunting and feasting in wild forested hills far away from the city (and my computer).

When writing about mythology, this blog traditionally concentrates on stories of the underworld and the dark beings and divinities which exist beyond the mortal veil. However to celebrate the wild joys of the forest, I am dedicating this week to Artemis/Diana–goddess of the hunt and protector of animals. Even though Artemis was primarily a virgin goddess of unspoiled wilderness, wild creatures, and of hunters and hunted, she had a dark underworld aspect as well. In stark opposition to her role as protector of children and women in childbirth she was a plague goddess who killed swiftly with afflictions which struck like divine arrows.

Artemis was the twin sister of glorious Apollo. Both siblings were the children of Zeus and Leto (a daughter of obscure Titans). Hera/Juno was angry about Zeus’ philandering and tried to prevent the birth of the twins by cursing the land they were born in, but Leto found a floating Island, Delos, which escaped Hera’s wrath by being unmoored. After the birth of the twins, Delos was cemented to the seafloor and became a sacred location.

Artemis was the elder twin. Although Leto bore Artemis quickly and painlessly, Apollo’s birth was a terrible ordeal of prolonged painful labor which lasted nine days and nights. By the end of this time, Artemis had grown into a full goddess and she helped her mother bring her twin into the world—hence her connection with childbirth. Thereafter Artemis was identified with the moon and the wilderness while Apollo has always been a sun god associated with civilization and society. When Artemis met Zeus she asked to always remain a virgin and a loner, a request which the king of the gods quickly granted to his lovely daughter.

Artemis had several attributes: a bow and a quiver full of arrows, a knee-length tunic, and packs of attendant hounds and nymphs. The sacred animal of Artemis is the deer, and she is often portrayed caressing a deer, being carried in a chariot drawn by deer with golden antlers, or hunting stags in the forest. One of Hercules’ most challenging labors was to capture a golden-antlered hind sacred to the goddess. The magical deer could outrun arrows (and anyways Heracles knew that shooting it would bring him the disfavor of the goddess and disaster). For a year he unsuccessfully pursued the deer on foot and he only succeeded in catching the doe when he fell down in desperation and groveled before the goddess (who transferred her wrath to Eurystheus). Another myth involving deer and Artemis does not end so well for the mortal protagonist. Once when she was bathing–nude, chaste, and beautiful—she was accidentally spotted by the unlucky Theban hunter Actaeon. In fury that a mortal had espied her loveliness, she transformed the hunter into a stag, whereupon he was torn to shreds by his own dogs–which did not recognize their master or know the anguished voice trying to call them off with the tongue of a deer. For some reason this scene is a timeless favorite of artists!

This last story hints at Artemis’ dark aspects. When wronged, Artemis was a fearsome being and her wild vengeance rivals that of any underworld deity. Several of the more troubling stories from classical myth involve her wrath. For example, her anger led directly to the Caledonian boar hunt, the defining heroic event of the era just prior to the Trojan War. One year King Oeneus of Calydon disastrously forgot to include Artemis in his annual sacrifices. To punish the King, she sent a monstrous male pig, a scion of the primal monster Echidna to ravage the countryside. This in turn brought the greatest hunters and heroes of Greece together with sad consequences. In other tales Artemis was even more direct with her vengeance. She visited plague upon Kondylea until the citizens adjusted their worship of her. She famously slew the many daughters of Niobe with painless arrows and turned their mother into a weeping stone.

Artemis is a self-contradicting figure–a virgin who was the goddess of childbirth; a protector of wild animals who was also goddess of the hunt; and a friend to maidens, mothers, and children who wielded the plague to smite down mortals. Her temples were frequently on the edge of civilization—at the end of the croplands where the forest began or at the edge of useable land where terra firma gave way to swamps and morasses. This highlights the main fact about Artemis—she was a nature goddess. wildness and inconsistency were parts of her. Worshiping Artemis was how the Greeks venerated and sanctified the savage beauty and random gore of the greenwood.