You are currently browsing the monthly archive for March 2013.

It’s been a while since Ferrebeekeeper featured a Gothic post–so here is one of my favorite sculptural details from world famous Notre Dame cathedral in the heart of Paris. An intense bearded man with a hand axe is pursuing a cockatrice (a poisonous two-legged rooster-dragon) along the top of a wall. The cockatrice was reputed to have the ability to turn people to stone so the particular realism of the axeman takes on an added dimension–but the monster is frozen as well (as it has been for the long centuries).

One of the ongoing horror stories from when I was in middle school was the invasion of the Africanized killer bees. In retrospect, it all sounds like a xenophobic horror movie from the 1950s, but people were truly alarmed back in the 80s. There were sensationalist news stories featuring the death of children and animated maps of the killer bees spreading unstoppably across America. The narrative was that mad scientists in South America had hybridized super-aggressive African bees with European bees in an attempt to create superbees (better able to survive in the tropics and produce more honey). These “Africanized” bees then escaped and started heading north, killing innocent humans and devastating local hives as they invaded.

The amazing thing about this story is that it is all true. In the 1950s a biologist named Warwick E. Kerr imported 26 queen bees (of subspecies Apis mellifera scutellata) from the Great Lakes area of Africa to Brazil. A replacement beekeeper allowed the queens to escape in 1957 and they began to interbreed with local bees (of the European subspecies Apis mellifera ligustica and Apis mellifera iberiensis). The resulting hybridized bees were indeed better able to survive the tropics and quicker to reproduce, but they were also more defensive of their hives, more inclined to sting, and more likely to swarm (i.e. get together in a big angry cloud and fly off somewhere else when they felt unhappy). The killer bees (for want of a better term) could more readily live like wild bees in ground cavities and hollow trees. The hybrid bees out-competed local honeybees and spread across the continent. Sometimes aggressive queens would enter domestic hives and kill the old queen and take over!

Although Ancient Egypt may have been an early adapter of apiculture, Sub Saharan African societies did not practice beekeeping but hewed to the ancient tradition of bee-robbing. The African subspecies of honeybees came from a more challenging environment than the European subspecies. Forced to contend with deep droughts and fiendish predators (like the infamously stubborn honey badger), the bees are more defensive and more mobile than their northern counterparts. Apis mellifera scutellata is famous for not backing down from raiders but instead stinging them with dogged determination until the intruder flees far from their hive. This has led to unfortunate instances of children, infirm adults, and people with bee allergies falling down and being stung to death (which sounds like a really bad end) by the American hybrid. The sting of an Africanized bee is no more puissant than that of a European honeybee (and it also results in the death of the bee) but dozens—or hundreds—of stings can add up to kill a healthy adult.

The entire Africanized bee event was really a case of anti-domestication. Imagine if everyone’s dogs were suddenly replaced by wolves or if placid white-and-black cows were supplanted by ravening aurochs. If you follow that bizarre thought to its logical conclusion, you will anticipate what actually happened. Although initially dismayed, Brazilian beekeepers began to discover more placid strains of Africanized bees and started to redomesticate them. The hybrid bees do indeed produce more honey, survive droughts better, and it is believed they have a greater resistance to the dreaded colony collapse sweeping through honey bee population. Perhaps in the fullness of time we will learn to love the infamous killer bees.

After several blog posts describing spaceplanes (like the sleek experimental British Skylon plane), it is time to write about one of the alternative proposals for reusable space-capable craft which are capable of both take-off and landing. In the old spaceman fantasies from the golden age of science fiction, human explorers flew their rockets to another world, dropped through the atmosphere and landed vertically. Their rocket set around while the astronauts had fantastical adventures. Then they rushed back aboard and blasted off!

Last week (March 7th, 2013) an experimental rocket named Grasshopper flew a record 80 meters (263 feet) before landing perfectly on the launch pad where it started. Grasshopper was built by Space Exploration Technologies or SpaceX, the private space transport company founded by PayPal billionaire, Elon Musk (who–based on his name and his legacy–may be a James Bond villain or an alien philanthropist). SpaceX is the first privately funded company to successfully launch a spacecraft into orbit and recover it and the budding company has also been first past numerous other milestones in the commercialization of space. Instead of giving everything Roman names like NASA, SpaceX gives its crafts and components Arthurian names such as Merlin, Kestrel, and Draco (I’m going to pretend there was a grasshopper at least somewhere in T. H. White).

The reusable first stage tests of Grasshopper are breaking new ground in the fields of guidance and stability (which are required to land a Grasshopper). If all continues to go well the company plans on supersonic tests later this year. As these become more glorious and more dangerous it is unclear if they will seek to have their current Texas facility made into an official spaceport or if they will move out to the blazing glory of White Sands with the Airforce, NASA, and Virgin Galactic. Whatever the case I salute them for flying a smokestack around the countryside and then landing it on a basketball court. Perhaps I was too hasty to dismiss the possibilities of commercial spaceflight!

In Latin, ashes are called cinis and , similarly, the Latin word for ashy gray or ash-like is cinereous. English borrowed this word in the 17th century and it has long been used to describe the color which is dark gray tinged with brown shininess. As with many Latin color names (like fulvous and icterine) the word cinereous is often used in the scientific name of birds which are very prone to be this drab color.

However, the concept of color is not quite as simple as it first seems. Different items produce ocular sensations as a result of the way they reflect or emit light, yet different wavelengths of light are visible to different eyes. Humans are trichromats. We have photoreceptor cells capable of seeing blue, green, and red. Most birds are tetrachromats and can apprehend electromagnetic wavelengths in the ultraviolet spectrum as well. Many of the dull cinereous birds we witness may glow and sparkle with colors unknown to the human eye and unnamed by the human tongue.

By far the most popular post on Ferrebeekeeper involves leprechauns. Because of this fact, the sporadic generic tips I receive from WordPress usually include advice like “maybe you should consider writing more about this topic.” This involves a conundrum, because leprechauns are totally made up. What else is there to be said about the little green fairy-folk without reviewing weird B movies or randomly posting leprechaun tattoos?

Fortunately today’s news has come to my aid. Apparently the world’s smallest park, Mill Ends Park, in Portland, Oregon was victimized by tree-rustlers who stole 100% of the park’s forest. This seems like grim news, but Mill Ends Park is very small indeed: the entire (perfectly circular) park measures 2 feet in diameter. Because of its dinky 452 square inch area, Mill Ends Park only contained one small tree. A drunkard might have fallen on it (the park is located on a traffic island in the midst of a busy intersection) or pranksters might have taken it away to a container garden. Maybe a German industrialist now has the little tree in some weird freaky terrarium…

Anyway, you are probably wondering why Portland has a park which is smaller than a large pizza and what exactly this has to do with imaginary fairy cobblers from Ireland. It turns out that Mill Ends Park was the literary confabulation of journalist Dick Fagan. After returning from World War II, Fagan began writing a blog (except they were called “newspaper columns” back then, and people were actually paid for them). In 1948, the city of Portland had dug a hole to install a street light on the median of SW Naito Parkway, but due to the exigencies of the world, the light never materialized. Fagan became obsessed with the pathetic little mud pit and began planting flowers in it and rhapsodizing about fantasy beings who lived there (whom only he could see). Fagan’s story of the park’s creation is a classic leprechaun tale. While Fagan was writing in his office, he saw a leprechaun, Scott O’Toole, digging the original hole (presumably to bury treasure or access a burial mound or accomplish some such leprechaun errand). Fagan ran out of the building and apprehended the little man and thus earned a wish. As mentioned, Fagan was a writer, so obviously gold was not his prime motivation. He (Fagan) asked the leprechaun (Scott O’Toole) to be granted his very own park. Since the journalist failed to specify the size of the park, the leprechaun granted him the tiny hole.

Fagan continued to write about the “park” and its resident leprechaun colony for the next two decades using it as a metaphor for various urban issues or just as a convenient frippery when he couldn’t think of anything to write about (a purpose which the park still serves for contemporary writers). In 1976, the city posthumously honored the writer by officially making the tiny space a city park. The little park frequently features in various frivolous japes such as protests by pipe-cleaner people, the delivery of a post-it sized Ferris wheel by a full-sized crane, and overblown marching band festivities out of scale with the microcosm.

True to form, the Portland Park Department was appalled at the recent deforestation and sprang into action by planting a Douglas fir sapling in Mill End Park. Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) are the second tallest conifers on Earth, and grow to a whopping 60–75 meters (200–246 ft) in height so it is unclear how this situation will play out over time, but presumably Patrick O’Toole and his extended Irish American family will be on hand to ensure that everything turns out OK.

The silver-gilt coronet of the 14th Earl of Kintore (you could have bought it at Christie’s for less than a used Trans Am)

A coronet is a small crown which is worn by a nobleman or noblewoman. In the European tradition coronets differ from kingly crowns in that they lack arches—they are instead simple rings with ornaments attached. Different ranks of nobility wear different coronets. For example, in England the various ranks are denoted as follows:

Marquess: that of a marquess has four strawberry leaves and four silver balls (known as “pearls”, but not actually pearls)

If you bothered counting the “pearls” and strawberry leaves on the above illustrations, you will recognize that certain adornments have been left out (which is to simplify the heraldic representation of coronets). I wish I knew what the strawberry leaves represent! If I was a sinister & bloodthirsty nobleman, that is not the sort of decoration I would choose for my fancy fancy hat, but maybe I am not thinking like a peer. Other western European nations have differently shaped coronets with different ornaments, but the same sort of rank-by-decoration pertains.

Coronets are largely symbolic—many nobles do not even have them made. By tradition they are worn only at the coronation of a monarch. Coronets are important however in heraldry, and the peerage rank of a noble house can easily be determined by looking at the little crown drawn on their shield.

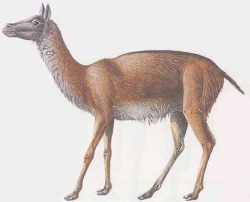

Camelids are believed to have originated in North America. From there they spread down into South America (after a land bridge connected the continents) where they are represented by llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos. Ancient camels also left North America via land bridge to Asia. The dromedary and Bactrian camels are descended from the creatures which wandered into Beringia and then into the great arid plains of Asia. Yet in their native North America, the camelids have all died out. This strikes me as a great pity because North America’s camels were amazing and diverse!

At least seven genera of camels are known to have flourished across the continent in the era between Eocene and the early Holocene (a 40 million year history). The abstract of Jessica Harrison’s excitingly titled “Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America” gives a rough overview of these huge extinct beasts:

Aepycamelus was the first camel to achieve giant size and is the only one not in the subfamily Camelinae. Blancocamelus and Camelops are in the tribe Lamini, and the remaining giant camels Megatylopus, Titanotylopus, Megacamelus, Gigantocamelus, and Camelus are in the tribe Camelini.

That’s a lot of camels–and some of them were pretty crazy (and it only counts the large ones—many smaller genera proliferated across different habitats). Gigantocamelus (as one might imagine) was a behemoth weighing as much as 2,485.6 kg (5,500 lb). Aepycamelus had an elongated neck like that of a giraffe and the top of its head was 3 metres (9.8 ft) from the ground. Earlier, in the Eocene, tiny delicate camels the size of rabbits lived alongside the graceful little dawn horses. This bestiary of exotic camels received a new addition this week when paleontologists working on Ellesmere Island (in Canada’s northernmost territory, Nunavut) discovered the remains of a giant arctic camel that lived 3.5 million years ago. Based on the mummified femurs which were unearthed at the dig, the polar camel was about 30 percent larger than today’s camels. The arctic region of 3.5 million years ago was a different habitat from the icy lichen-strewn wasteland of today. The newly discovered camels probably lived in boreal forests (rather in the manner of contemporary moose) where they were surrounded by ancient horses, deer, bears and even arctic frogs! Testing of collagen in the remains has revealed that the camels are closely related to the Arabian camels of today, so these arctic camels (or camels like them) were among the invaders who left the Americas for Asia.

The bones are a reminder of how different the fauna used to be in North America. When you look out over the empty, empty great plains, remember they are not as they should be. All sorts of camels should be running around. Unfortunately the ones that did not leave for Asia and South America were all killed by the grinding ice ages, the fell hand of man, or by unknown factors.

Today Ferrebeekeeper travels far back in time across the long shadowy ages to the Western Zhou dynasty to feature this goose-shaped bronze zun (a ceremonial wine vessel). The Western Zhou dynasty lasted from 1046–771 BCE and was marked by the widespread use of iron tools and the evolution of Chinese script from its archaic to its modern form. Excavated in Lingyuan, Liaoning Province in 1955 this goose vessel is now held at the National Museum of China. I like the goose’s neutral expression and serrated bill!

People love citrus fruit! What could be more delightful than limes, grapefruits, tangerines, kumquats, clementines, blood oranges, and lemons? This line of thought led me to ask where lemons come from, and I was surprised to find that lemons–and many other citrus fruits–were created by humans by hybridizing inedible or unpalatable natural species of trees. Lemons, oranges, and limes are medieval inventions! The original wild citrus fruits were very different from the big sweet juicy fruits you find in today’s supermarkets. All of today’s familiar citrus fruits come from increasingly complicated hybridization (and attendant artificial selection) of citrons, pomelos, mandarins, and papedas. It seems the first of these fruits to be widely cultivated was the citron (Citrus Medicus) which reached the Mediterranean world in the Biblical/Classical era.

The citron superficially resembles a modern lemon, but whereas the lemon has juicy segments beneath the peel, citrons consist only of aromatic pulp (and possibly a tiny wisp of bland liquid). Although it is not much a food source, the pulp and peel of citrus smells incredibly appealing–so much so that the fruit was carried across the world in ancient (or even prehistoric times). Ancient Mediterranean writers believed that the citron had originated in India, but that is only because it traveled through India to reach them. Genetic testing and field botany now seem to indicate that citrons (and the other wild citrus fruits) originated in New Guinea, New Caledonia and Australia.

In ancient times citrons were prized for use in medicine, perfume, and religious ritual. The fruits were purported to combat various pulmonary and gastronomic ills. Citrons are mentioned in the Torah and in the major hadiths of Sunni Muslims. In fact the fruit is used during the Jewish festival of Sukkot (although it is profane to use citrons grown from grafted branches).

Since citron has been domesticated for such a long time, there are many exotic variations of the fruit which have textured peels with nubs, ribs, or bumps: there is even a variety with multiple finger-like appendages (I apologize if that sentence sounded like it came off of a machine in a truck-stop lavatory but the following illustration will demonstrate what I mean).

Citron remains widely used for Citrus zest (the scrapings of the outer skin used as a flavoring ingredient) and the pith is candied and made into succade. In English the word citron is also used to designate a pretty color which is a mixture of green and orange. I have writted about citrons to better explain the domestication of some of my favorite citrus fruits (all of which seem to have citrons as ancestors) but I still haven’t tried the actual thing. I will head over to one of the Jewish quarters of Brooklyn as soon as autumn rolls around (and Sukkot draws near) so I can report to you. In the mean time has anyone out there experienced the first domesticated citrus?

The world’s rarest and most precious pearls do not come from oysters, but instead from very large sea snails of the species Melo melo. Melo melo snails lives in the tropical waters of southeast Asia and range from Burma down around Malysia and up into the Philippines. The snails are huge marine gastropods which live by hunting other smaller snails along the shallow underwater coasts of the warm Southeast Asia seas.

Melo melo is a very lovely snail with a smooth oval shell of orange and cream and with zebra stripes on its soft body. The shell lacks an operculum (the little lid which some snails use to shut their shells) and has a round apex as opposed to the more normal spiral spike. This gives the Melo melo snail’s shell a very aerodynamic lozenge-like appearance (although living specimens look more like alien battlecraft thanks to the large striped feet and funnels). The animals grow to be from 15 to 35 centimeters in length (6 inches to a foot) although larger specimens have been reported. The shell is known locally as the bailer shell because fishermen use the shells to bail out their canoes and small boats.

Melo pearls form only rarely on the snails and are due to irritating circumstances unknown to science. No cultivation mechanism exists (which explains the astronomically high prices). A single large melo pearl can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars or more in Asia. The pearls are usually egg-shaped or oval (although perfectly round specimens are known) and they can measure up to 20-30mm in diameter. Not nacreous (like pearls from oysters & abalones), these valuable objects have a porcelain-like transparent shine. Melo pearls are brown, cream, flesh, and orange (with the brighter orange colors being most valuable).

Apart from the fact that they come from a large orange predatory sea snail, what I like most about melo pearls is the extent to which they evoke the celestial. It is hard not to look at the shining ovals and orbs without thinking of the sun, Mars, Makemake, and Haumea. Rich jewelry aficionados of East Asia, India, and the Gulf states must agree with me. It is difficult to conceive of paying the price of a nice house for a calcium carbon sphere from an irritated/diseased snail, unless such pearl spoke of unearthly beauty and transcendent longing.