You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Jiajing’ tag.

新年快乐! Happy Lunar New Year!

The Chinese new year which begins on February 10, 2024 (or really “Year 4722” in the Chinese calendar) is the Year of the Wood Dragon! Although this blog has not been around for the full 4722 years, we have been around for longer than a full 12 year zodiac cycle, so you can peer back through the mists of time to the long-vanished 2012 (Year of the Water Dragon) to see what personality traits are characteristic of people born in dragon years (although in that bygone post, I forgot to mention that dragons’ lucky color is glorious golden yellow).

In the Chinese zodiac bestiary, dragons stand out as the only mythical creature out of the twelve which do not exist in nature (although it has been suggested that dragons could potentially be based on crocodiles, giant catfish, or dragonlike fossil creatures which are now extinct–all of which seem like intriguing possibilities).

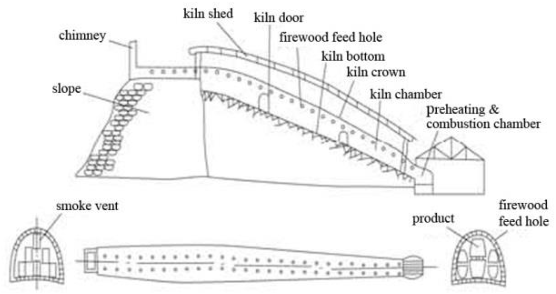

Yet even if dragons don’t exist in nature, there are certainly plenty of dragons in Chinese art and culture…and there are “dragons” climbing the Chinese hills. The world-famous South Chinese stoneware (which is literally synonymous with China in English) was manufactured in “龙窑”, “lóng yáo“, which translates as “dragon kilns”. In order to reach and maintain the high temperatures (1100° to 1400 °C) necessary for the production of fine stoneware, ancient potters created multi chambered kilns which climbed backwards up the steep hills. The highest chambers maintained the highest and most stable temperatures and are where the most exquisite pieces of Chinese porcelain were (and are) fired. The top chambers were also where the smokestacks were located, so, when the kilns were operating, they looked like enormous segmented creatures climbing the picturesque wooded hills and belching smoke! lóng yáo indeed!

These kilns worked very well indeed…and they were enormous: vast numbers of porcelain vessels could be efficiently fired together at one time with a single load of fuel. Here in the year of the wood dragon it is worth remembering that all of China’s ancient porcelain was indeed belched out by a wood fed dragon! Yet what we at ferrebeekeeper are most concerned with are the fruits of these labors–the exquisite stoneware porcelain and fine ceramics of dynastic China. In this realm too, the dragon reigned supreme, as a timeless emblem of the Chinese state (except during the Yuan/Mongol dynasty, when dragons lacked the same governmental cache in the eyes of horse-oriented steppe-based overlords). It seems like 2024…err I mean “4722” is going to be a true year of struggle, strife, and change. As we fight our way through the mayhem, let’s pause to recall what is sidereal, ideal, and eternal by posting some dynastic dragon porcelain from ancient China.

To celebrate Lunar New Year, here is a first example, a glorious enamelware dragon vase from the Ming Dynasty (during the Ming era, yellow was reserved for ceramics of the imperial household). This piece is from the fascinating (and troubled) JiaJing period (1522 to 1566), so it was being fired in a dragon kiln just before Shakespeare was born. With any luck, there will be plenty more lovely dragon vessels to see here as we move onward through the year of the dragon, but for now best wishes for prosperity, happiness, and love in the new year!

No series about the cities of the dead would be complete without a visit to the world’s most populous country, China. Because of China’s 5000 year+ uninterrupted cultural history, there are some extraordinary examples to choose from, like the Western Xian tombs, or the world famous Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, a circular tomb with a circumference of 6.3 km (3.9 miles) and an army of more than 7000 life-sized earthenware soldiers (they don’t build ’em like that anymore, thank goodness). However for artistic reasons, Ferrebeekeeper is going to highlight the most well-known tomb complex in China–the Ming tombs which is a compound of mausoleums built by the emperors of the Ming Dynasty from 1424 to 1644 on the outskirts of Beijing. Indeed today the tombs are now in a suburb of Beijing, surrounded by banks, residential housing parks, and golf courses.

The First Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor, whose rags-to-riches story has no obvious equivalent in history, is NOT buried in the Ming tombs (although don’t forget to follow this spooky link to read about his horrifying excesses), nor is his successor, the Jianwen Emperor, who was usurped and vanished from history. However the third and greatest Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, the mighty Yongle Emperor is buried there. The Yongle Emperor chose the spot according to principles of Feng Shui (and political calculus) and he and 12 other Ming dynasty emperors were interred there along with a dynasty worth of empresses, concubines, favorite princes, et cetera etc. Each of the 13 mausoleums has its own name like the Chang Ling Mausolem, which is tomb to the Yongle Emperor, or the Qing Ling Mausoleum which is the final resting place of the Tai Chang Emperor.

Some of the subjects of past Ferrebeekeeper posts can be found buried in the Ming Tombs–like the Jiajing Emperor (who is in the Yong Ling Mausoleum, if you are keeping track of this at home). Considering how much mercury that guy drank, he is probably perfectly preserved somewhere in there glistening like the silver surfer even after all of these years.

I say probably, because we don’t know. Only three of the 13 tombs have been properly excavated and explored by archaeologists (these known tombs are the tombs of the Yongle Emperor, Longqing Emperor, and the Wanli Emperor). In 1644, the whole necropolis was looted and burned by Li Zicheng, the first (and last) Emperor of the ill-fated Shun Dynasty, but, fortunately, he seems to have burned and looted tombs the way he set up kingdoms–very badly and incompletely. This means there are ten whole tomb complexes of China’s richest greatest emperors which are awaiting the archaeologists of the future (probably…it is always possible that one of China’s more recent autocrats secretly looted everything and sold it to dodgy collectors or hid it under his bed). Imagine the unknown treasures awaiting discovery!

The first paragraph alluded to the artistic merit of this graveyard, and I really meant that. Just look at the beauty of the Sacred Way in the top photo (this is the main entrance to the tombs which Emperors would traverse when visiting the spot to pay homage to their predecessors) or the ceremonial chamber form the Ding Ling Tomb (which is the third image down). Best of all, we have an amazing painting (below)! Look at the this beautiful watercolor map/landscape painting from the late nineteenth century which shows the entire tomb complex (the painting itself belongs the Library of Congress). Naturally, if you click the painting it will not blow up to full size here (thanks to the hateful anti-aesthetic nature of WordPress). However here is a link to the original image at Wikipedia, you can expand it to immense size on your computer and take a personal tour of one of the world’s most lovely and historically significant tomb complexes.

Ming week was last week, and, even though there is so much more to say about the Ming Dynasty, I need to wrap up and move on to other topics. Today’s visual post will have to serve as an epilogue. Here is an epic panoramic painting of the Jiajing Emperor traveling to the Ming Dynasty Tombs with a huge cavalry escort and an elephant-drawn carriage. The work was completed at some point during the Jiajing reign (1522-1566) but I haven’t been able to pinpoint the date any better than that (it is such a huge painting, that maybe it took the whole forty years to make). You should really click on the painting above. It shows up as a little mummy-colored hyphen only because WordPress and I are so computer illiterate. If you click on it, it is actually a 26 meter (85 ft) long epic scroll showing the enormous imperial entourage progressing towards the beautiful and spooky necropolis of the Ming Emperors. What could be a more appropriate postscript to the pomp and dark absolutist majesty of that erstwhile time?

I hope you enjoyed the thrilling rise of the Hongwu Emperor as related in yesterday’s post. In accordance with the wishes of the editors who commissioned it, I left out the truly important parts—namely, how the Hongwu Emperor organized the Ming dynasty around Confucianist precepts, cunning agrarian reform, and above all—naked absolutism. I also left out the terrible end of Zhu Yuanzhe’s story arc: for the skills and guile which allowed the Hongwu Emperor to seize absolute power had a terrible shadow side. As an old man, he was seized by dreadful paranoia and employed vast armies of secret police, informers, and torturers to root out the imaginary plots which flowered on all sides of him. Hongwu killed hundreds of thousands of people by means of the most inventive and horrible tortures. Despite his astonishing feats, and despite the prosperity he brought to China, his name is permanently blackened by the depths of his cruelty (although Mao admired him).

It almost makes you wonder if leaders aren’t inherently flawed somehow: as though there is some fundamental problem with putting self-interested individuals in charge of our collective destiny.

But today’s post is not about leadership; it is about beautiful & delicate Chinese porcelain! It would be unthinkable to have a Ming Week which didn’t feature a fine Ming vase. Here is a Ming dynasty vessel from the Jiajing reign (1522-1566). The Jiajing emperor was a weakling and a fool who devoutly believed in all sorts of portent, rituals, astrology, and mystical claptrap. His courtiers and eunuchs used this to control him while they robbed the Empire to the brink of disaster. Infrastructure was neglected. Crooked courtiers ground the peasants down into crippling destitution. The social fabric unwound.

But what did the rich and powerful care when they lived in an era of such luxury? Porcelain of the Jiajing reign is particularly whimsical and otherworldly. This vase shows the “three friends” pine, bamboo, and plum growing together as emblems of wealth, happiness, and longevity. Each plant is twisted into an otherworldly logogram–a “shou” symbol. Here the plum blossoms forth out of a splendid stylized rock covered in lichen.

Look at the decorative elements! The waves, the scrolls, and the mystical vegetation which surround the three central plants all began as naturalistic forms—but by the time of the Jiajing era they have been transmuted into ethereal blue beauty. And yet the original forms are still there as well. It is hard to describe what gives this little ovoid vase its winsome charm, but the aesthetic effect is undeniable.

Large bowl with design of miniature potted plants (Ming dynasty, Jiajing mark and period, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, Porcelain; underglaze blue-and-white; Tianminlou collection)

It’s been a while since we had any posts about how beautiful trees are. Therefore here are two Ming Dynasty bowls which feature tree art. The first bowl above is rather large and dates back to the reign of the Jiajing emperor (which lasted from 1521 AD to 1567 AD). The Jiajing emperor was a noted loon who believed absolutely in magical portents and auspicious signs—which in turn made him a pawn to corrupt court officials who used the monarch’s credulity as an opportunity to steal and/or ruin everything. However the emperor’s obsession with magic meant that Jiajing-era porcelain was marked by a beautiful sense of occult whimsy and Taoist fantasy. This bowl shows four different potted plants: a cypress, a pine, a peach, and a bamboo which are growing in a beautiful garden filled with butterflies, cicadas, and dragonflies. The plants are shaped in the form of four different auspicious words fu, shou, kang, and ning (happiness, long life, health, and composure).

The second bowl is smaller and arguably finer. It also shows a garden scene bounded beneath by two ornamental borders of extreme elegance and beauty. A dwarf flower tree is bursting into blossom among spring foliage (the opposite side of the bowl shows a bamboo grove). Inside the bowl is a beautiful miniature garden of rocks, bamboo, and flowering trees. The tiny bowl was manufactured during the Chenghua reign (from between 1464 AD and 1487 AD) which was a troubled era of court intrigues and palace murders (which took place at the orders of the villainous concubine, Lady Wan). This little bowl, however, is exquisite and seems to have escaped the shadows of its era. For half a millennium the tiny perfect Ming garden has been blooming in delicate shades of cobalt glaze.

The eleventh Emperor of the Ming dynasty, the Jiajing emperor, who (mis)ruled China from 1521 to 1567, was a tremendously devout taoist. During the Jiajing reign, Taoist symbolism became omnipresent in art and culture–especially near the end of the emperor’s reign when his fanatical search for immortality began to bring ruin to China. Jiajing porcelain is distinct in that the robust naturalism of earlier Ming blue and white ware is replaced by increasingly fanciful imagery. Cranes, dragons, phoenixes, immortals, and flaming pearls all float through a dreamlike magical world. Sorcerers and magicians frolic happily through scerene forests filled with deer, pine, fungi, and bamboo (all of which are symbols of immortality or longevity). Frilly clouds complete the picture of whimsical abandon. Even the shape of porcelain became more fanciful: to quote the website Eloge de l’Art par Alain Truong, (which contains many fine photographs of Jiajing porcelain, several of which are used here), “The double-gourd is a popular symbol of longevity and is associated with the Daoist Immortal Li Tiegui, who is depicted holding a double gourd containing the elixir of immortality.” The vase at the top of the article, which shows a lighthearted scene of people playing in a garden is double gourd shaped. Here are some additional examples of Jiajing porcelain:

Another lovely blue and white double gourd vase also reflects the Jiajing zeitgeist. On this vase, an auspicious crane flies throught the clouds above a powerful dragon.

This small jar portrays the four Daoist Immortals Li Tieguai, Liu Hai, Hanshan and Shide dancing in a pine forest beneath swirling clouds.

‘Shou’ is the symbol for longevity. This double vase presents numerous shou medallions of various sizes embedded in a matrix of clouds and flames.