You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘birth’ tag.

In years past, Ferrebeekeeper has celebrated Saint Patrick’s Day with a series of short essays about Irish folklore. We started with leprechauns and worked our way through the doom of Oisin (who could have had eternal youth and endless love), the Sluagh (evil spirits who ride the clouds), the Leannán Sídhe, the Fear Gorta, and the great Gaelic flounder (which is not even a thing, but which should be). You should read that story about Oisin–it’s really plaintive!

Anyway, this year we are going to take a break from the disquieting beauty of Irish folklore to showcase a category of obscene Medieval sculpture, the “Sheela na gig”, a sort of stylized stone hag who is portrayed holding open her legs and her cavernous womanhood (a word which I am primly using as a euphemism for “vagina”). These grotesque female figures appear throughout Northwest Europe, but are most prevalent in Ireland. Nobody knows who carved them or why. Their name doesn’t even have a coherent meaning in Gaelic. Yet they are clearly connected to fertility and to the great mother goddess of the Earth. As you can imagine, they are the focus of furious speculation by religious and cultural mavens of all sorts. However no definitive answer about the nature of the figures has ever been found…nor is such an answer ever likely to be forthcoming.

Sheela na gigs were mostly carved between the 9th and 12th centuries (AD) and seem to be affiliated with churches, portals, and Romanesque structures. Although they are located throughout central and western Europe, the greatest number of Sheela na gig figurines are located across Ireland (101 locations) and Britain (45 locations). To the prudish Victorian mind they were regarded as symbols for warding off devils (which would be affrighted by such naked womanhood?), however more modern interpretations empower the sculptures with feminist trappings of matriarchy, self-awareness, sexual strength, and shame-free corporeality. Perhaps the stuffy Victorian misogynists were the devils who needed to be scared off! Other scholars think of the Sheela na gig figurines in the vein of the pig with the bagpipes or the “Cista Mystica“–which is to say a once widespread figure which had a well-understood meaning which has become lost in the mists of long centuries (it is easy to imagine future generations looking at Hawaiian punch man, Bazooka Joe, or the Starbucks logo with similar bafflement).

Some scholars have theorized a connection with Normans–and hence with Vikings–but I see little of Freya in the images (which seem more connected to prehistoric “Venus” statues).

It is probably ill-advised to opine about such a controversial figure, but if I were forced to guess, I would suspect that the Sheela na gig is a symbol of the generative power of Mother Nature (or the godess Gaia) which is so overt as to barely be a symbol. All humans were born through bloody expulsion. We do not come into the world through a magic emerald cabbage or a portal of light. Whatever else the Sheela na gig betokens, it is a reminder of this shared heritage (which you would think would be impossible to forget…until you talk to some of the people out there).

According to ancient Chinese mythology, humankind was created by the benevolent snake-goddess Nüwa (who is one of my very favorite divinities in any pantheon, by the way). But keen readers wonder: where did Nüwa come from? Whence came the ocean and the earth and the sea and the winds and the heavens. Oh, there is a story behind that too, but it is strange and troubling—sad and incomplete and beautiful like so much of Chinese mythology and folklore.

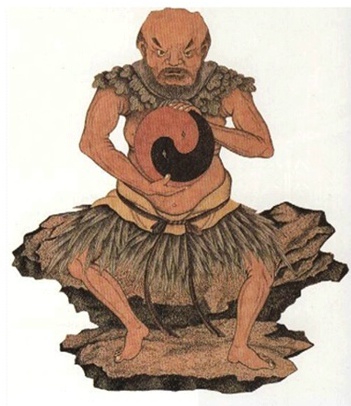

In the beginning there was nothing except for the universe egg—a vast perfect egg which contained everything. Within the universe egg, yin and yang energies were mixed together so completely and perfectly that they were indistinguishable. Then, through some unknown means, the egg changed—mayhap it became fertilized—and a being began to grow within it. This was P’an Ku, the great primordial entity. The yin and yang energy began to separate and build complex forms. P’an Ku slowly grew and grew. He started as something infinitely small but gradually he became larger and larger until eventually his vast arms came up against the sides of the everything egg. The little embryo became a vast god. The walls of the egg became a prison.

Then P’an Ku grabbed an axe (which appeared from who knows where). Using all of his gargantuan might, he smashed a great blow through the shell of the egg, which exploded. He was born—as was the universe. Beside him, in the gushing yolk, the primordial magical beings came into being—the dragon, the tortoise, the phoenix, and the quilin. These special creatures helped the first deity as he began to separate chaos into order. P’an Ku split the yin into darkness and the yang into light. He laid the foundation stones of the vault of the everlasting sky and filled the ocean with the waters of creation dripping from the shattered egg shell.

But as he built, a strange thing happened (though maybe not so strange to my fellow artists who can never quite craft their dreams into their works). The world he made became inimical to him. He aged. He suffered. His creation was unfinished…and he died. His breath became the clouds and the wind. His body became the mountains and the plains of China. His eyes became the sun and the moon. The hair of his body and head became the plants and trees.

It was in this corpse-world that the creator deities moved: Nüwa, a child born of P’an Ku’s genitals…or an alien outsider? Who knows? Who can say? What is important is that eggs are important. In Chinese myth they are the source of everything. The beginning of the universe.

Chinese mythology does not dwell on the end of the world quite the way other cosmologies do. Our world is sad and broken enough that we don’t need to think about its ending. But there are ethereal hints from before the Chin emperor’s great purges which suggest that time is circular like an egg. Somehow, as we all began, so we will end back there again in the homogenized grey yolk of chaos.

Ever since recounting the story of Orpheus, I have been thinking about the lyre. The ancient musical instrument even showed up again last week in a post about an amazing new planetary system–and the mythical harp of the gods somehow stole some of the glory from real worlds formed eleven billion years ago. Perhaps this is appropriate: for the myth of the first lyre is a story of theft.

It is also the origin story of Hermes, who was not just the messenger of the gods, but also the god of tradesmen, herdsmen, and thieves. Hermes was the child of Maia, the daughter of a Titan. After the war between Titans and Olympians, she hid herself away in a stygian cave which twisted down beneath Mount Cyllene, but one day, Zeus spied her and they became lovers. Maia’s cave provided the dallying pair with an excellent hiding place from the jealous eyes of Hera, and in due course Hermes was born. Even as a baby, the obstreperous little god, was too clever and mischievous to be hidden away in some cave. Baby Hermes sneaked out and soon found a herd of exquisite white cattle belonging to Apollo. The tiny god picked out the finest of these splendid sky cattle and rustled them off for himself and his mother, but before leading them away, he put brooms on their tails so they would erase their tracks. He also drove them out of their pasture backwards and disguised his own footprints by wearing branches on his feet. Then he took the white cows to a secret grove and sacrificed the two most beautiful beasts, burning everything but the entrails. These gut strings he attached to a turtle shell to play soothing music—the first lyre!

When Hermes got back to his cave, his mother was frantic with worry, but he quickly beguiled her with honeyed words and a sweet lullaby. In the meantime, Apollo had noticed that his best cattle were missing, and he began to hunt the thief… but it was no easy task. First the golden god could not find any tracks, and when he discovered the footprints, they lead back to the paddock (and there was no evidence of any thief). However Apollo was the god of prophecy and hidden truth, so he drew upon his divine augury to discover who had taken his cattle. In fury he rushed into Maia’s cave to grab the culprit, but, even as an infant, Hermes was swift and he outran the angry sun god. Soon the comic chase lead up to Olympus, where a proud Zeus, made the (half) brothers cease their quarrel.

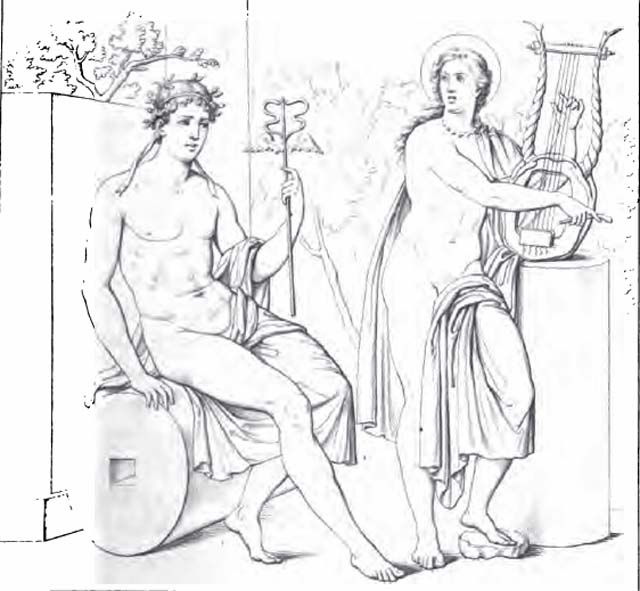

Hermes returned the cattle, but two were still missing! Apollo demanded them back, but to no avail: they were burned up. Hermes pulled out his lyre hoping to lull Apollo as he had Maia, but the lovely music had an altogether different effect on the refined art-lover Apollo. As the god of music and beauty, Apollo was indeed beguiled, but he did not fall asleep. Instead he had to have the beautiful instrument! He begged his little brother, and cajoled, and finally offered him all the white cattle. Hermes drove a hard bargain and he also gained Apollo’s magical wand in the deal. This wand was the fabulous and disturbing caduceus—a winged golden rod wrapped by two snakes. It became the symbol of Hermes, and of commerce itself, but, according to myth it had yet deeper powers—to grant sleep, and death, and resurrection. Hermes touched the eyes of the departed with the caduceus and led them on their last journey. He used it to transcend the thresholds of the world and travel everywhere (although in the modern world it has become meddled with the staff of Asclepius).

Apollo received the lyre, and it became his defining symbol (along with his golden bow). In fact Apollo’s lyre became the symbol of all art and music–a role which it still holds. It is funny that the defining objects of the two gods were originally vice-versa (though maybe knowing mothers–and knowing merchants–will not find such a swap entirely unprecedented).

In the Greco-Roman cosmology, the underworld was a fearsome place not just for mortals, but for the gods themselves. For one thing, only a handful of deities had full freedom of passage to the realm of the dead. Hades reigned there and could come and go as he pleased (though, like a grumpy rich man, he seldom left his dark palace). Persephone’s annual journey to Hades and back defined the seasons. Mysterious Hecate, the goddess of magic and thresholds could go anywhere at all, as could Hermes, the fleet-footed messenger of the gods (and the psychopomp who guided departed spirits to the final door). Nyx, alien goddess of primordial night, existed before the underworld…or anything else…and will exist long after. Although his retirement palace was in Tartaras, the deposed king of the gods Cronus/Saturn seems to have been free to roam the firmament. The Erinyes, spirits of furious retribution could temporarily leave the underworld only in order to goad their charges there…and that is about the full list. There were a lot of deities imprisoned in the underworld and there were lesser deities who worked there…but they were permanently stuck. Feasibly the Olympians, the most powerful gods who ruled heaven, the seas, and earth, could enter the underworld and leave again, but they never deigned to do so. Gaia had the underworld within herself, so she stands beyond the paradigm (and perhaps the abstruse children of Nyx do too…but they were tangential to classical myth).

There is of course an important exception. One Olympian god was the child of a mortal mother. Because of this human origin, and due also to his fundamental gifts and nature, he took the heroes’ journey and went down into the realm of the dead. Here is the myth. I have hesitated to tell it before for personal reasons: this god is one of my two favorite Greek gods but he is also my least favorite—the rewards, delights, and downfalls of worshiping him are all too evident!

Anyway…

Semele was a beautiful princess. From heaven Zeus spied her beauty: he courted her and won her heart (without using subterfuge or force), but, unfortunately, his lack of guile allowed jealous Hera to easily discover the affair. The angry queen assumed the guise of an ancient crone and paid a visit on the lovely young princess. The crone flattered the princess and fussed over her whims until Semele was convinced the old woman was a dear friend. Then Hera asked who the father of Semele’s unborn child was (for the princess was just beginning to show her pregnancy).

“The father is none other than mighty Zeus, king of all the gods,” announced the princess.

“Eh, I wonder…” replied the old woman. “All sorts of scoundrels have grandiose pretensions and men will tell any blasphemous lie to seduce a beautiful princess. Zeus? King of all the gods? What nonsense. Back when I was young and beautiful, I used to have a no-good man who told me the same thing. If he really is Zeus, why doesn’t he show himself to you in his full splendor.”

Doubt grew in Semele’s heart. Who was her handsome lover, really? When next he was in her arms, she resolved to find out. Using all of her beauty and wiles she cajoled Zeus and beguiled him and convinced him to promise her a boon. She even made him swear on the River Styx–a sacred oath, binding even upon the gods.

“If you are Zeus, show yourself to me in all of your divine splendor!” she demanded. Zeus equivocated and explained. Finally he outright begged to be free of his promise, but Semele was adamant: he had sworn an unbreakable oath. Sadly Zeus selected his smallest thunderbolt and gathered his most quickly passing squall. For an instant only, the sky father revealed himself as a force of nature with all the power and glory of the heavens, but an instant of such revelation was too much. Semele was burned away and only a pile of ash remained…and a pre-term baby. In horror and sorrow, Zeus grabbed up the little fetus. He hacked a hole in his “thigh” and sewed the tiny demigod into his own body (online classicists have informed me that “thigh” is a euphemism which decorous 19th century myth writers used for gonads). Then he set off for Nysa, a valley at the secluded edge of the world. The king of the gods knew exactly who was responsible for Semele’s death, and he wanted his son to grow up free from Hera’s wrath.

When Zeus reached Nysa, he gave birth to Dionysus directly from his “thigh.” Zeus then gave the beautiful infant to the wild nymphs of Nysa–the maenads–to raise. The maenads brought the child up with their own intuition, wildness, and delirium. Leopards and tigers were his playmates. At the eastern edge of the world strange indecipherable noises could sometimes be heard. Grapes grew there too in superabundance, and the child demigod realized how to make them into sweet intoxicating wine. He grew into an inhumanly beautiful adolescent. Then he clad himself in glorious purple robes and began to make his way through the world towards civilization (which, coincidently for this Greek myth, was Greece).

Everywhere Dionysus went he brought the secret of wine making. Sometimes he rode in a leopard drawn chariot with throngs of naked maenads running before him wildly singing his glory. Other times he revealed his divine nature to humankind differently—more subtly…or more strangely! But the ecstasy, beauty, and power of his gifts of inebriation always became readily apparent. Dionysus grew into the god of art, fertility, drama, and creation, but there is delirium, madness, anti-creation, and an orphan’s violent sadness to him as well.

In his wild youth as a demigod in the mortal world, Dionysus had many adventures (in fact, we’ll circle back to some of these stories in later posts). Although he was powerful, he was youthful, delicate, graceful, and kind. Clad in purple robes, half-human & half-divine, asking us to drink his wine of revelation…he seems terribly familiar. At the end of his pilgrimage through Greece he came to Olympus and he effortlessly ascended up it to join his father among the other gods. His divinity was obvious to all. Hestia stood up from her throne and offered it to her nephew and went over to take a place at the hearth. Hera gritted her teeth and plotted how to win other battles. Zeus beamed and asked his son if there was anything he wanted as a gift on the special occasion of his apotheosis.

For all of his wild delirium, Dionysus was a kind god…and an orphan. He plaintively asked his father if he could see his mother. Zeus readily assented…and then some. He told Dionysus to go get his mother and to bring her back to Olympus. And so it was. Dionysus went to the underworld and took his mother’s spirit away from ignominious death up to the glory of the heavens. The underworld part of this story is an afterthought—a tiny grace note at the very end. However it is worth remembering that Dionysus’ story runs through the world and the underworld. Drink and delirium are also keys to the realm of the dead, as any tragedian or hardened boozer could readily tell you.

This is the Ferrebeekeeper’s 300th post! Hooray and thank you for reading! We celebrated our 100th post with a write-up of the Afro-Caribbean love goddess, Oshun. To celebrate the 300th post (and to finish armor week on a glorious high note), we turn our eyes upward to the stern and magnificent armored goddess, Athena, the goddess of wisdom.

Athena’s birth has its roots in Zeus’ war with his father Cronus. In order to win his battle against the ruling race of Titans (and thus usurp his father’s place as the king of the gods), Zeus married the Titan Metis, goddess of cunning and prudence. Her wise counsel and crafty stratagems gave the Olympian gods and edge against the Titans and the latter were ultimately cast down. Metis was Zeus’ first wife and the secret to his success… but there was a problem. It was foretold that Metis would bear an extremely powerful offspring: any son she gave birth to would be mightier than Zeus. To forestall this problem Zeus tricked Metis into transforming into a fly and then he sniffed her up his nose so that he could always have her cunning counsel inside his head. But Metis was already pregnant. Inside Zeus’ skull she began to craft a suit of armor for her child to wear. The pounding of her hammer within his temples gave Zeus a terrible headache. Insane with pain, Zeus begged his ally Prometheus (the seer among the Titans) to cure him of this misery through whatever means necessary. Prometheus seized a labrys (a double headed axe from Crete) and struck open Zeus’ head with a noise louder than a thunderclap. In a burst of radiance Athena sprang forth fully grown and clad in gleaming armor.

Athena was Zeus’ first daughter and his favorite child. For his own armor, Zeus had carried an invincible aegis crafted out of the skin of his foster mother, the divine goat Amalthea. When Athena was born he handed this symbol of his invincible power over to her. Similarly throughout classical mythology Athena is the only other entity whom Zeus trusts to handle his lightning bolts (there is an amazing passage in the first lines of the Aneid where she vaporizes Ajax’s chest with lightning, picks him up with a whirlwind, and impales him on a spire of rock in revenge for an impiety). Her other symbols were the owl, a peerless predator capable of seeing at night, and the gorgon’s head, a magical talisman capable of turning humans to stone (which Athena wore affixed to her armor). Although she was first in Zeus’ esteem, Athena did not forget her mother’s fate and she remained a virgin goddess who never dallied with romance of any sort.

Wisdom, humankind’s greatest (maybe our only) strength was Athena’s bailiwick as too were the fruits of wisdom. Athena was therefore the goddess of learning, strategy, productive arts, cities, skill, justice, victory, and civilization. She is often portrayed as the goddess of justified war in opposition to her half-brother Ares, the vainglorious deity representative of the senseless aspects of war. In classical mythology Athena never loses. Her side is always victorious. Her heroes always prosper. She was the Greek representation of the triumph of creativity and intellect.

Metis never bore Zeus a son to usurp him–but when I read classical mythology such an outcome always seemed unnecessary. Not only did Athena wield Zeus’ authority and run the world as she saw fit, but Zeus was perfectly happy with the arrangement (a true testament to her wisdom). The one slight to the grey eyed goddess is that she does not have a planet named after her (nor after her Roman name Minerva), however I have always thought that astronomers have been secretly saving the name. We can use it when we find a planet inhabited by beings of greater intelligence, or when we travel the stars to a second earth and apotheosize into true Athenians.