You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘darkness’ tag.

Imagine a flood of pure inky darkness spreading inexorably across the land and destroying all living things in Stygian gloom. Well…actually you don’t have to imagine it. Such a phenomena exists! When rain falls immediately after forest fires, the baked earth can not absorb any water and all of the ash, char, and soot become a gelatinous flash flood. I have never mastered the WordPress tool for videos, but you can see such a flood by following this link. I was fascinated by the horrible, otherworldly sight and I watched the clip again and again, but, be warned, it is as troubling and awful as it sounds (perhaps more so, since such events spell toxic doom for any aquatic or amphibious animals living in arroyos, riverbeds, and floodways so afflicted).

So why am I posting this unwholesome sight during this already dark plague year? It is a warning, obviously. After one thing goes horribly awry, it is all too easy to start a chain reaction of bad things which ruin the land itself. Lately (since 2016) things have been going wrong in all sorts of directions. We need to prepare for attendant woes and gird ourselves against them. We also need to guard our forests against fire (and axes, invasive pests, and industrial mayhem).

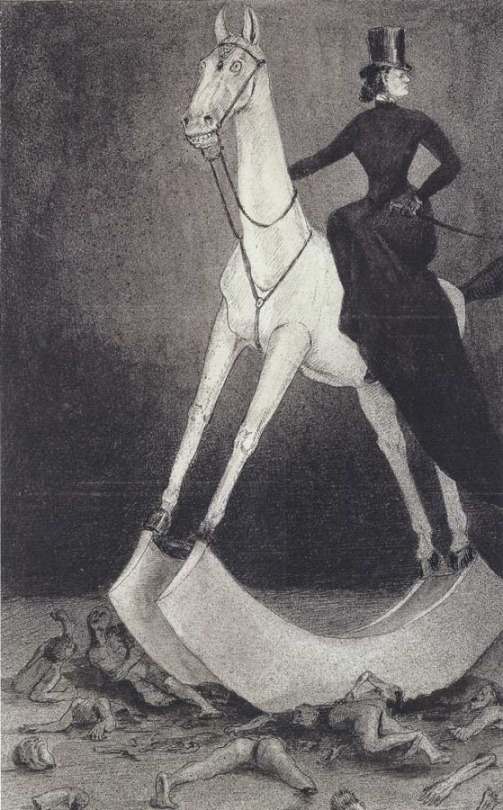

Lady on the Horse (Alfred Kubin, 1938, Pen and ink, wash, and spray on paper)

Alfred Kubin was born in Bohemia in 1877 (Bohemia was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Like many people, Kubin could see the direction which Austrian society was taking, and it seemed to rob him of direction. As a teenager he tried to learn photography for four pointless years from 1892 until 1896. He unsuccessfully attempted suicide on his mother’s grave. He enlisted and was promptly drummed out of the Austrian army. He joined various art schools and left without finishing. Then, in Munich, Kubin saw the works of symbolist and expressionist artists Odilon Redon, Max Klinger, Edvard Munch, and Félicien Rops. His life was changed—he devoted himself to making haunting art in the same vein. His exquisite mezzotint prints are full dream monsters, spirit animals, ghosts and victims. These dark works seemed to presage the era which followed. Yet throughout the nightmare of both World Wars and the post-war reconstruction, Kubin lived in relative isolation in a small castle.

After Anschluss in 1938, Kubin’s work was labeled degenerate, yet his age and his hermit life protected him and he continued working through the war and until his death in 1958. In later life he was lionized as an artist who never submitted to the Nazis (although possibly he was too absorbed in his own dark world to notice the even darker one outside).

The North Pole (Alfred Kubin 1902)

Kubin’s beautiful prints look like the illustrations of a children’s book where dark magical entities broke into the story and killed all of the characters and made their haunted spirits perform the same pointless rituals again and again. Great dark monuments loom over the lost undead. Death and the maiden appear repeatedly, donning their roles in increasingly abstract guise until it is unclear which is which.

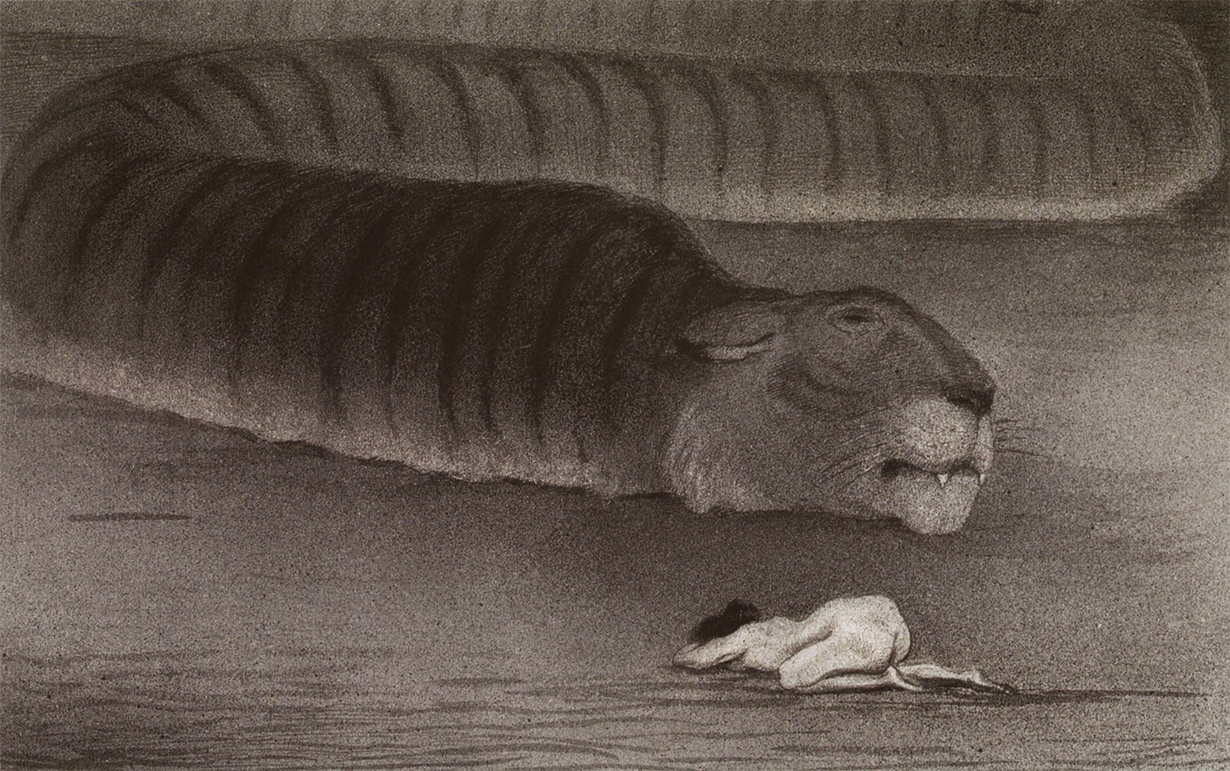

The Pond (Alfred kubin, ca. 1905)

My favorite aspect of the works are the shadow monsters and hybrid animals which often seem to have more personality and weight than the little albescent people they prey upon. The gloomy ink work is so heavy it seems to lack pen strokes—as though Kubin rendered these little vignettes from dark mist.

The Egg (Alfred Kubin, 1902)

Kubin’s imagery was naturally seen through the psychosexual lens of Freudianism. He was claimed by the symbolists, and the expressionists. Yet his work seems to really exist in its own mysterious context. Kubin’s greatest works seem to involve a narrative which the viewer does not know, yet the outlines of which are instantly recognizable (like certain recurring nightmares).

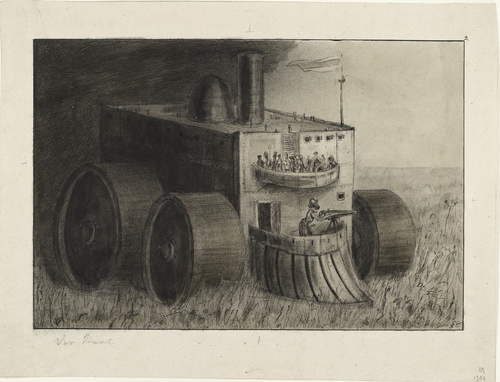

The Government (Alfred Kubin)

Gifted in multiple ways, Kubin wrote his own novel, The Other Side, which has been compared to Kafka for its dark absurdity. I certainly haven’t read it, but if anyone knows anything about it, I would love to hear more below. In the meantime look again at this broken world of Gothic horror and wonder. Then maybe go have some candy and enjoy some flowers. There is plenty more dark art coming

Snakes in the City (Alfred Kubin,1911, pen and ink)

This blog has always been dedicated to the dark ones beneath the earth—the beautiful and horrible deities of the underworld! So today we will look at Etruscan gods of death and the afterlife. Sadly most of Etruscan literature and mythology has been lost, so in some cases all we have is obscure names. In the spirit of religion and mythology, I will try to make up for the lack of textual evidence with lurid pictures, extravagant adjectives, and outright supposition.

Much of Etruscan myth was strongly influenced by (or outright based on) Greek mythology. Aita was the equivalent of Hades who ruled over a similar underworld of spirits, monsters, and fallen gods. Aita’s wife “Phersipnai” was the unchanged analog of Greek Persephone. There were unique figures of the Etruscan cosmology who continued to have a hold on Roman practices and beliefs: like the “manes” which were the spirits of the dead which lingered near tombs and gravesites. There were also entities like Charun who were extremely unlike their Greco-Roman counterparts. Etruscan mythology as a whole has a bestial and naturalistic undertone of animal-human deities, human sacrifice, and violence.

To make this more straightforward (and to make this a coherent article—since data is scarce about some of these deities), here is an alphabetical list:

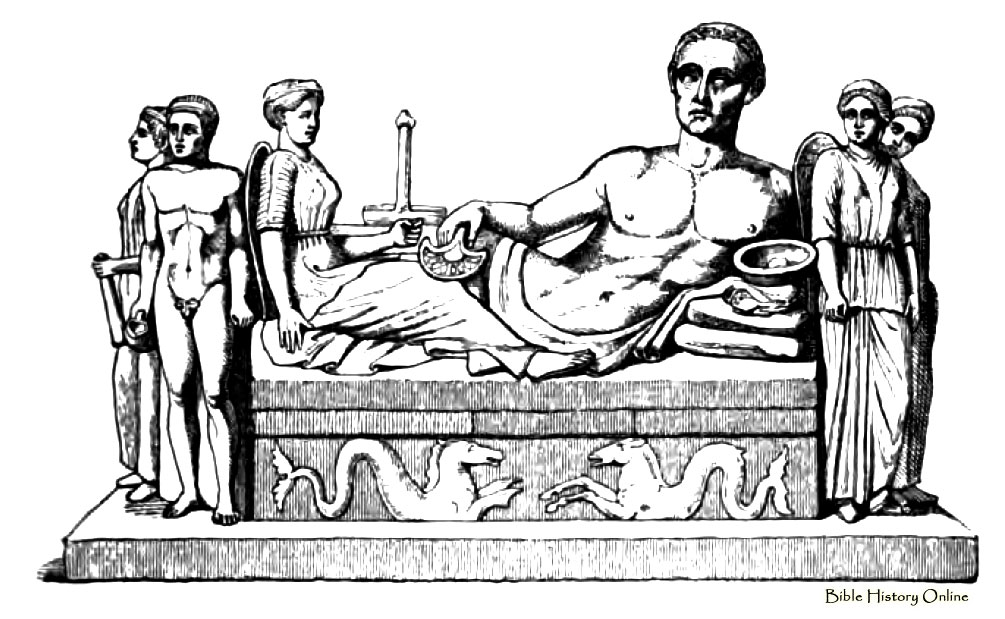

Aita Conjuring. A relief carved on a 2nd c BC ash urn from Perugia, in the Museo Etrusco Romano at Perugia. Drawing from Otto Volcano, Die Etrusker.

Aita: The Lord of the underworld: equivalent to the Greek Hades.

Calu: A mysterious savage underworld being who is a hybrid of wolf and man.

Charun: A blue skinned demon covered with snakes and carrying a hammer, Charun guided deceased spirits to their final home in the underworld. He is sometimes also depicted with boar’s tusks, a vulture’s beak, a huge black beard, and/or giant black wings. Charun was essentially the Etruscan spirit of death.

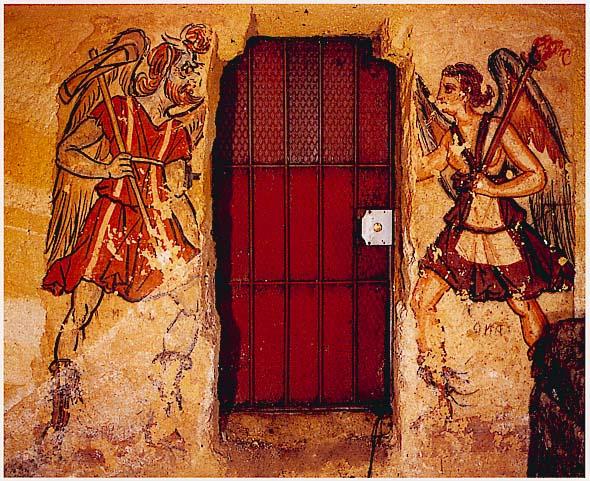

Culsu (AKA Cul): Pictured with scissors and a torch, Culsu was a female chthonic demon of gateways.

Letham (Lethns, Letha, Lethms, Leta) An Etruscan infernal goddess about whom little else is known. Worship her at your peril!

Mania: Reported to be the mother of the Lares and Manes, Mania was a dark goddess of the dead and the undead. According to ancient traditions and Roman legends about Etruria in the era of the pre-Roman kings, Mania was the central figure of the Laralia festival on May 1st when children were sacrificed to her. Mania was quietly worshipped in Roman times and had a position in medieval and modern Tuscan folklore as a goddess of nightmares and demons.

Phersipnai (Phersipnei, Proserpnai): The wife of Aita and queen of the underworld; a figure nearly identical to the Greek Persephone and Roman Proserpina.

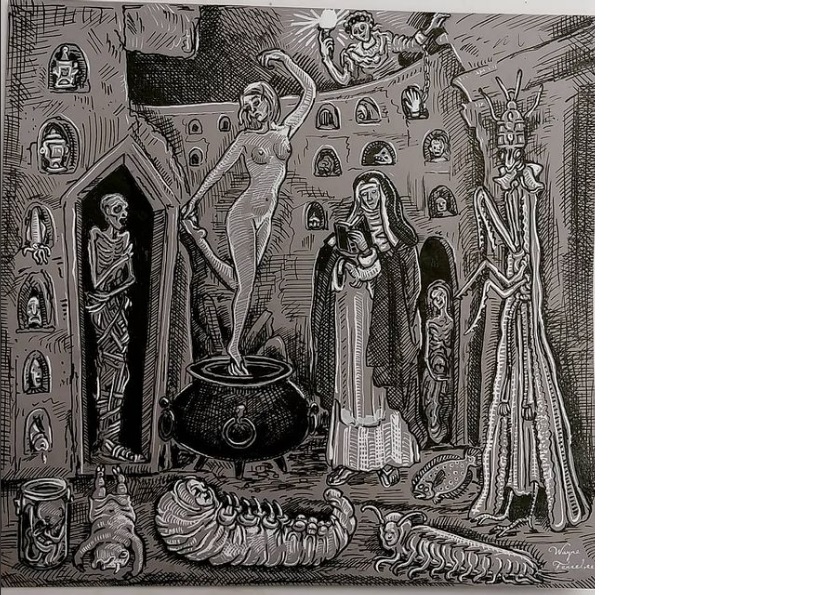

Vanth: A winged goddess of the underworld who together with Charun acted as a psychopomp. She is usually portrayed with a kindly face and with bare breasts crossed by straps. She sometimes holds a key, a light, or a scroll and she tends to dress in a chiton. I wonder if her imagery didn’t skip over classical Rome, because (aside from her toplessness) she could easily be a Christian angel on the payroll of Saint Peter.

I have done the best I could describing the underworld deities of Etruria. Of course, since everything about Etruscan society seems to involve ancient disputes, scholarly misunderstanding, and Roman fabrication, I have probably messed up substantially and I beg your understanding and forgiveness (particularly if you happen to be some terrifying fanged Etruscan death god). There is also a final mysterious category of Etruscan deities which should be mentioned—the Dii Involuti, “the hidden gods” who acted as a final arbiter of affairs both human and divine. These guys sound extremely scary and powerful and belong on any list of underworld deities. Unfortunately, in complete accordance with their name, I could not find out anything about them!

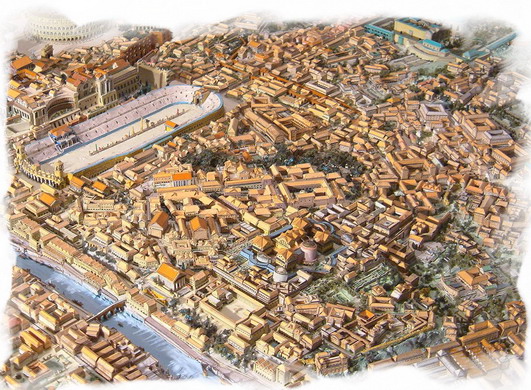

Ferrebeekeeper has described all sorts of gods and goddesses of the underworld—we have covered deities of plague and of darkness, gods of death and betrayal, and all sorts of dark rulers of the next world, however there were also gods of the criminal underworld. In the Roman pantheon, the goddess Laverna was the deity of thieves, dishonest tradesmen, cheaters, and frauds. Although stories about Laverna are scant (since her worshippers did not necessarily want to flaunt their devotion) she is mentioned in the works of Plautus and Horace and her sacred sanctuary was near the Porta Lavernalis (a gate in the Servian walls which opened from the Aventine into a thief-infested grove of trees). Various unsavory stretches of highway and dangerous urban groves throughout Italy were sacred to Laverna as well. It has been speculated that she was originally a chthonic goddess of the Etruscans.

Laverna’s attributes were darkness and secrecy. Her worshippers are said to have poured out libations to her with their left hands only. There is a (probably apocryphal) myth about Laverna which illustrates her nature. She appeared disguised as a beautiful noblewoman to a rich devout man and asked him to grant her lands to establish a temple to some other more mainstream Roman deity. She earnestly promised the wealthy patron to honestly uphold her duty by swearing an oath upon her body itself. When she received control of the lands, she robbed them blind, sold everything worth any gold, and then sold the land itself before disappearing with the lucre. Her patron was distraught and he appealed to the Olympians to bring her to justice (based on the strength of the oath she swore). The gods heard his prayers and they sought out Laverna to make her pay, but when they caught up with her she was only a head—having used thievish magic to make her body incorporeal. Having no body (at least temporarily) she was free from the onus of her contract (although she probably looked pretty weird as just a flying head).

Almost every culture has myths and stories about the undead—supernatural beings trapped between the living world and the underworld. The majority of such creatures are horrible, monstrous, or sad, yet such is their dark hold on our imagination that they reoccur in the legends of many different places.

This year, in order to celebrate Halloween, that special time between seasons when the veil to the underworld if lifted, Ferrebeekeeper presents some of the undead who are less familiar than Hollywood’s smooth-talking vampires and shambling zombies. Although undead folklore stretches back to prehistory, an appropriate place to begin with our exploration is in the cemeteries and columbariums of Ancient Rome–which were haunted by several sorts of undead spirits. Roman funereal practice changed back and forth from burial to cremation several times (and some families or individuals preferred to stick with the unfashionable tradition). Cemeteries and funereal monuments were found by the side of thoroughfares just outside of towns and cities. One can imagine how spooky these unlighted tombs were at night when filled with footpads, desperate fugitives, wild animals, and pre-industrial darkness (even without the various wandering dead whom the Romans believed in).

The most common Roman apparitions were two sorts of ghosts: the manes and lemures, which were separated by moral alignment. Manes, the spirits of deceased loved ones, were basically benevolent– although they still enjoyed drinking blood, which Romans provided for them with animal sacrifices and with gladiatorial games (which were originally intended for funereal purposes). Wealthy Romans held sumptuous feasts to satiate the manes, and even people of more humble means sacrificed and gave offerings to the spirits of the dearly departed. The lemures, however, were not so benevolent. These were dark and restless spirits who died bad deaths. Some lemures were forever lost and could not find the underworld. Others were tied to this world through foul acts or evil temper. The lemures were imagined as shapeless black forms of malevolence. Romans tried to placate the lemures with sacrificial offerings of funereal black (most often black beans, superstitiously cast behind—although other black sacrifices are hinted at).

Beyond such ghostly revenants, Romans greatly feared witches and the liminal tricks which they could play with life and death. Anyone who has read The Golden Ass will recall the indelible first story within a story–wherein the wicked Thessalonian sorceresses Meroë and Panthia kill the narrator’s friend, drain his blood, and rip out his heart which they replace with a sponge. After an agonizing night of fear, debasement, and suicidal thoughts, the narrator is delighted when dawn breaks and his murdered friend is alive (all the night’s horrors merely a dream). The two men proceed out of town and stop at a spring to drink, whereupon the sponge in the murder victim’s chest falls out and he falls drained & dead upon the sand (The Golden Ass is an unrivaled work of literature, but not for the faint of heart).

The Romans also feared the Lamiae. According to myth, Lamia was a beautiful Libyan queen who was loved by Zeus, but something went (badly) awry with their affair and Lamia wound up devouring her only child and pulling out her eyes. Thereafter she roved the dark on a serpent’s tail looking for other children to devour. The Romans were fascinated by this horrifying figure, and in later Roman folklore the Lamiae are an entire category of monster rather than one being. These later Lamiae were able to alter their appearance to become fair. They would then seduce young men and eat their life essence. The Romans were not the only ones fascinated by this kind of misogyny mythology and the Lamiae outlived the manes, lemures, and witch-cursed victims, to find a place in 19th century poetry and art.

There are no primary written sources concerning Slavic mythology–no myths written in the original languages, no poems, or songs, or tales of gods and heroes. The first people to write about the Slavic faith were Christian proselytizer, and their accounts are naturally hostile to the pagan faith. This means that we know tantalizing hints about Slavic deities from archaeology and we have some hair raising accounts from Christian sources (which are probably slander), but we actually know very little. One of the deities who has gained the most mileage from this dearth of information is the dark accursed god Chernobog (aka Crnobog, Czernobóg, Černobog, Црнобог, Zernebog and Чернобог).

A German priest traveling among unconverted Wendish and Polabian tribes wrote about Chernobog as a god of woe whose name meant “black god”. The name also shows up in a smattering of other sources which reveal little–but other than that Chernobog is largely unknown. While this would be a big problem for a harvest god or a love goddess, Chernobog is an underworld deity and his mysterious nature has made him popular with artists, movie makers, and video game producers looking for a big scary guy who doesn’t talk too much.

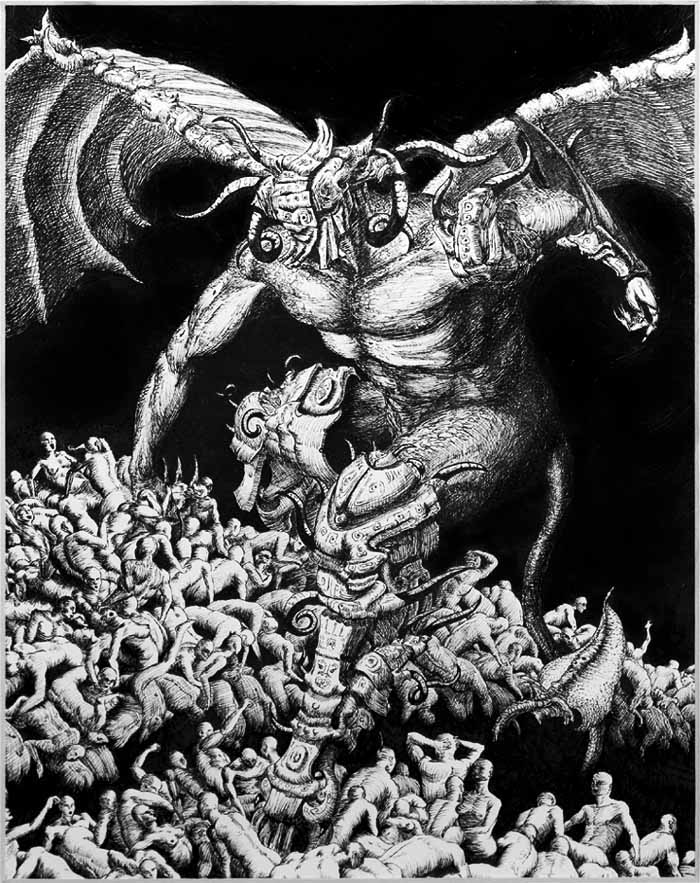

The most famous Chernobog appearance was in the Walt Disney film Fantasia, where he starred (as “Chernabog”) in the animated “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence. As Modest Mussorgsky’s wild tempestuous music plays, Chernabog, a huge winged demon of blackness, summons forth evil spirits and the restless undead to a lightning scarred mountain top (only to be banished by dawn and the ringing of a church bell). The sequence made a huge impact on me when I saw it on VHS in music class in elementary school and apparently I am not alone, Wikipedia had a long list of fantasy writers who have since used the character as a villain (the most intriguing-sounding of which was an alternate history of Russia where a comet impact had caused widespread famine and cannibalism and Chernobog was worshipped as a major deity!).

Perspicacious readers will probably notice I have just written a post concerning deities of the underworld based on almost no real information other than modern fantasy/entertainment–but there is a useful lesson here. If you are stuck for material Chernobog is your man–his fearsome aura of mystery and dreadful (albeit ambiguous) name will do your work for you.

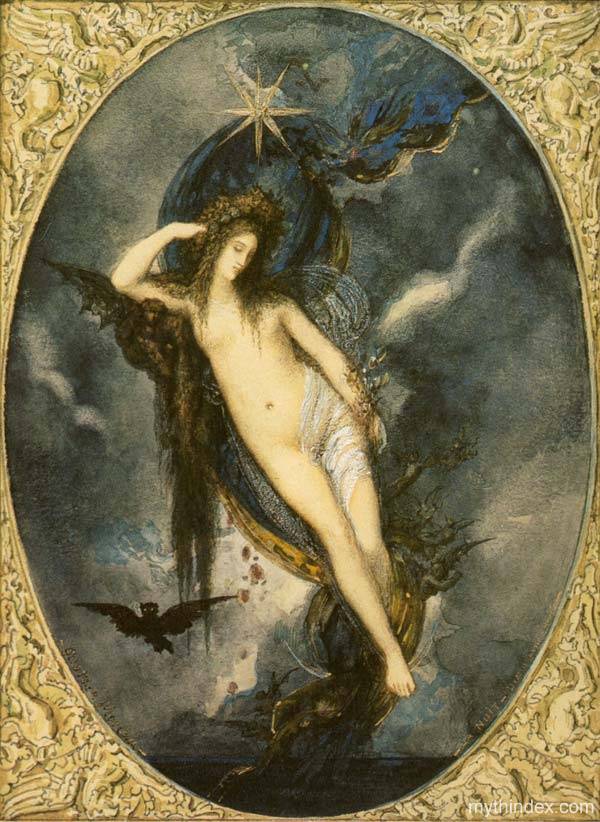

One of the most enigmatic Greek divinities is Nyx, the primordial goddess of the Night. In Hesiod’s Theogeny she was a child of Chaos, but, in other texts, Nyx was present at (or before) creation and had no parents. She is rarely mentioned in classical texts, but the few times she does appear are noteworthy. Some of her children include Death (Thanatos), Sleep (Hypnos), Mockery (Momus), Dreams (Morpheus), and the Fates (Moirae)–they represent various slantwise forces which even the Olympian gods are subject to.

One of the most enigmatic Greek divinities is Nyx, the primordial goddess of the Night. In Hesiod’s Theogeny she was a child of Chaos, but, in other texts, Nyx was present at (or before) creation and had no parents. She is rarely mentioned in classical texts, but the few times she does appear are noteworthy. Some of her children include Death (Thanatos), Sleep (Hypnos), Mockery (Momus), Dreams (Morpheus), and the Fates (Moirae)–they represent various slantwise forces which even the Olympian gods are subject to.

Nyx is mentioned in Chapter XIV of Homer’s Illiad, when the sleep god Hypnos refuses to carry out Hera’s bidding. Hypnos describes the past results of putting Zeus to sleep (against Zeus’ will) and relates how his mother saved him:

“Jove was furious when he awoke, and began hurling the gods about all over the house; he was looking more particularly for myself, and would have flung me down through space into the sea where I should never have been heard of any more, had not Night who cows both men and gods protected me. I fled to her and Jove left off looking for me in spite of his being so angry, for he did not dare do anything to displease Night. And now you are again asking me to do something on which I cannot venture.” [Forgive the Roman names—I used the Johnson translation for ease of citation and copying. Also, obviously, Nyx is called “Night” as she is in the rough Aristophanes quote below. I’ll try to find some prettier translations later.]

Nyx is also mentioned in Orphic cult poetry (certain mystery cult poems were attributed to the demigod Orpheus) where she is portrayed as a bird/woman with black wings who first created the universe. She dwells in a cave at the edge of the Cosmos. With her in the eternal darkness is Kronos, Zeus’ father, who was savagely mutilated by his son. Kronos is unconscious, drunk on magical honey, and he mutters prophecies which Nix then chants. Outside the cave is Zeus’ nursemaid, Adrasteia, who acted as mother for the king of the gods during his boyhood. Adrasteia keens and beats a cymbal to Nyx’s chanting and the entire universe subtly moves to the rhythm of her cymbal.

Aristophanes alludes to the Orphic mystery poetry in a chorus from his play “The Birds”. The chorus is sung by birds who have a different take on creation. In their interpretation, night is a bird and they are descended from her via love and chaos. Here is the relevant portion of their song:

…At the start,

was Chaos, and Night, and pitch-black Erebus,

and spacious Tartarus. There was no earth, no heaven,

no atmosphere. Then in the wide womb of Erebus,

that boundless space, black-winged Night, first creature born,

made pregnant by the wind, once laid an egg. It hatched,

when seasons came around, and out of it sprang Love—

the source of all desire, on his back the glitter

of his golden wings, just like the swirling whirlwind.

In broad Tartarus, Love had sex with murky Chaos.

From them our race was born—our first glimpse of the light

not before Love mixed all things up. But once they’d bred

and blended in with one another, Heaven was born,

Ocean and Earth—and all that clan of deathless gods.

Thus, we’re by far the oldest of all blessed ones,

for we are born from Love. There’s lots of proof for this.

We fly around the place, assisting those in love—

[Translation by Ian Johnston]

Although a few small temples and cults to Nyx existed, she was not often worshiped openly in Greece (nor, for that matter, were her children). However Nyx was in the background of many other god’s temples and ceremonies as a statue or a sacred phrase. Around her name and mythos was an impalpable shroud of ambiguity. To the Greeks, Nyx was older and stranger than the gods they cared about and worshiped–she was the first and original outsider.