You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘predators’ tag.

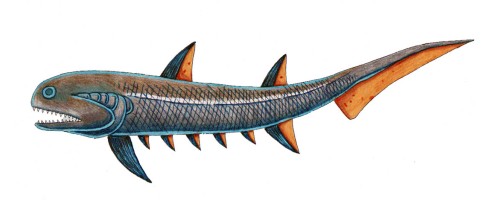

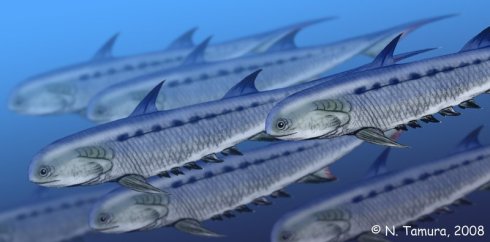

I promised this blog would feature more fish this year, but thus far, all we have seen is the remarkable ocean sunfish…so today we travel way back in time to the oceans of the Paleozoic world to check out some spiny sharks. However these “sharks” are really different from what you are probably expecting! During the Late Silurian and Early Devonian the oceans were filled with Climatius reticulatus a fish which took up a niche analogous to great schools of anchovies & sardines which swim in today’s oceans. Climatius reticulatus grew to be only 7.5 centimetres (3 inches) long! Some of these remarkable illustrations are bigger than they were! I am calling them “sharks” because they are indeed commonly known as spiny sharks, but they are more properly acanthodians—an early order of jawed vertebrates which shared some features with both bony fish and cartilaginous fish. Climatius reticulatus did have a cartilaginous skeleton, so don’t go thinking I am completely misleading you with quotation marks and paleontological hokum.

Although this fish was tiny with a squishy skeleton, it was not defenseless: each little Climatius sported fifteen razor sharp spines. Presumably they also swam together in great schools which would dazzle and mislead predators of long ago just as shoals of fish do today. Speaking of which, the predators of 420 million years ago were most likely anomalocaridids (horrifying giant arthropods, which were on their way out) cephalopods, and scary new vertebrate predators like Dunkleosteus.

Climatius was itself a predator too. It had a powerful caudal fin and large complicated eyes in order to find and capture the little animals swimming in the plankton of the ancient seas. The first acanthodians had appeared in the ocean back during the Ordovician (the age of cephalopods). They predate sharks and bony fish and were probably related to a basal ancestor of both. By the early Devonian, however the bony fishes were coming into their own and fierce competition from these magnificent teleosts soon drove the thriving schools of Climatius (and other similar acanthodians) into oblivion.

This blog frequently describes mammals which are extinct or not well known—creatures like the pseudo-legendary saola, the furtive golden mole, or the long-vanished moeritherium, however today Ferrebeekeeper is going all out and writing about one of the wild animals which people think about most frequently.

The brown bear (Ursus arctos) is beloved, feared, worshipped, hunted, despised, and glorified by humankind. These great bears are arguably the largest land predator alive today (their only rival is their near-cousin, the polar bear). A Kodiak brown bear can weigh up to 680 kg (1500 lbs) and stand 3 meters (10 feet) tall when on two legs. Brown bears can run (much) faster than the fastest human sprinter. Likewise they can climb and swim better than we can. They are literal monsters—mountains of muscle with razor sharp teeth and claws. However, bears have become so successful and widespread not because of their astonishing physical prowess, but because of their substantial intelligence.

Ursus arctos live in India, China, the United States, Russia, and throughout Europe. Because they live across such a broad swath of planet Earth, brown bears are divided into nearly twenty subspecies, but these various brown bears all share the same basic characteristics and traits. Brown bears are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, but they can hunt and forage during the day if it daylight suits their needs. Since they are ingenious omnivores, they are capable of living in many different landscapes and habitats. Usually solitary by nature, the bears sometimes gather together in large numbers if a suitable source of nutrients becomes available (such as a salmon run, a dump, or a meadow full of moth larva). The bears eat everything from tiny berries and nuts on up to bison and muskox. Although the majority of bears live primarily by foraging, some families are extremely accomplished at hunting. Brown bears pin their prey to the ground and then begin devouring the still living animal. This ferocious style means that humans greatly fear bear attacks, even though such events are extremely rare everywhere but Russia (where all living things continuously attack all other living things anyhow).

Bears are serial monogamists: they stay together with a single partner for a few weeks and then move on romantically. The female raises the cubs entirely on her own. Gravid bears have the remarkable ability to keep embryos alive in a suspended unimplanted state for up to six months. In the midst of the mother bear’s hibernation, the embryos implant themselves on the uterine wall and the cubs are born eight weeks later. Remarkably, if a bear lacks suitable body fat for nursing cubs, the embryos are reabsorbed.

Experts believe that brown bears are as intelligent as the great apes. There is evidence of bears using tools, planning for the future, and figuring out formidable puzzles (although they are terrible at crosswords). Their high intelligence can make bears seem endearingly human—as in the case of a beer-drinking bear from Washington State. After drinking one can of a fancy local beer and one can of mass market Busch, the bear proceeded to ignore the Busch while drinking 36 cans of the pricier local brew before passing out. There are famous bear actors with resumes more impressive than all but the most elite film stars. In other cases, bears and people have worked together less well. Brown bears used to live throughout the continental United States, but they were hunted to death.

“The figure of a shaman’s bear ally, paws outstretched, ready to assist in healing. It comes from the Nanai people and was collected in the Khabarovsk region in 1927. The “healing hands” of this bear were held to be especially helpful in treating joint problems.” (from http://arctolatry.tumblr.com)

Humans and bears have a love-hate relationship: although bears have been driven out of many places where they once lived, the practice of bear-worship was so widespread among circumpolar and ancient people that there is even a word for it: “arctolatry”. Bear worship is well documented among the Sami, the Ainu, the Haida, and the Finns. In pre-Roman times, bears were worshiped by the Gauls and the British. Artemis has a she-bear form and is closely associated with Ursus Major and Ursus Minor. Yet bear worship stretches back beyond ancient times into true prehistory. Cult items discovered in Europe suggest that bears were worshiped in the Paleolithic and were probably of religious significance to Neanderthals as well as Homo Sapiens. Indeed, some archaeologists posit that the first European deities took the form of bears.

Aww! Wook at the wittle puddy-tat… Argh! Wait, that isn’t a puddy cat at all, it is actually Felis silvestris lybica, the African wildcat, a formidable crepuscular predator which ranges across the Sahara and Sahal up through the Arabian Peninsula and around the Caspian Sea. Although they are remarkable hunters, African wildcats are not large—males measure 46–57 cm (18–22 in) in head-to-body length (discounting the elegant tail) and weigh from 3.2 to 4.5 kg (7 to 10 lbs). Using stealth, speed, retractable claws, and athletic lunges, the wildcats hunt and kill everything smaller than themselves: small mammals are their main prey but cats also kill birds, reptiles, insects, amphibians, and miscellaneous arthropods. African wildcats hunt mostly at dawn and dusk, but thanks to incredibly keen senses, they can also hunt at day or night.

The senses of the African wildcat are truly astonishing. Their large vertically slitted eyes are extremely efficient in brightest day or in the faintest light (thanks partly to the tapetum lucidum—a layer of reflective cells at the back of the eye which reflects light back into the photoreceptors). Wildcat hearing is among the best in the animal kingdom—they can hear many ultrasonic noises inaudible to humans and dogs (cats developed this sense because many rodents and insects communicate with such noises). Their large mobile ears further augment their acute hearing. Although they do not have the unbelievable noses of dogs or wolves, wildcats have an amazing sense of smell which is estimated to be 14 times more acute than a human’s. Additionally, their heads (and particularly their faces) are covered with vibrissae (whiskers) to help wildcats sense vibrations and navigate in tight pitch black spaces.

As well as keen senses, African wildcats possess other features which help them fit into their harsh arid environment. They have striped stippled coats which are the color of rocks, dry grass, and earth—so they blend in to most environments effortlessly (although they tend to have lighter colored bellies). Living in vast deserts, African wildcats have shockingly efficient kidneys. The animals can live without water on the fluid from prey animals. If necessary, they can rehydrate with seawater. They can also survive extremely hot temperatures and do not show discomfort until 52 °C (126 °F).

Felis silvestris lybica is actually one of several subspecies of old world wildcat Felis silvestris which ranges across all of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Wildcats are very, very versatile, resilient, and effective predators, yet all of the subspecies of wildcat are gradually losing their genetic diversity except for the African wild cat. This is because of interbreeding with the domestic cat Felis silvestris catus. As you have probably gathered by now, domestic cats descend directly from a handful of African wildcats which were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago when humans first became grain farmers. The first domestic cat was found buried in a Neolithic grave in Cyprus which dates back to 9,500 years ago. The wildcats (Felis silvestris) are all fully fertile when breeding across species, so some of the differences between the wildcat and the domestic cat are fairly arbitrary.

Today we feature one of everyone’s favorite animals–the great toothwalkers of the northern oceans, the mighty walruses (Odobenus rosmarus). Adult Pacific male walruses can weigh more than 2,000 kg (4,400 pounds) and grow to lengths exceeding 13 feet. The huge pinnipeds live in vast colonies ringed around the Arctic Ocean. Females separate themselves from the fractious males in order to protect their calves from the squabbling and dueling of the bulls. The tusks (which can grow to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in length) are also used by both genders to leverage their great weight out of the water—hence the name “toothwalker.” The word walrus comes from the Old Norse word “hrossvalr” which means horsewhale.

The distinctive face of the walrus is a mass of large coarse bristles properly known as vibrissae. Like the barbells of a catfish, these vibrissae are extremely sensitive tactile organs which help the walrus find shellfish on the dark and turbid ocean bottom. Walruses are capable of diving deep to find the invertebrates they like to eat. Scientists have recorded dives of 113 meters (371 feet) which lasted for about 25 minutes. Once the walruses have located a food source to their liking, they dislodge their prey with jets of water and then suction up the creatures. Apparently they are most partial to bivalve mollusks, snails, sea cucumbers, and crabs, but in extreme circumstances they can hunt large fish or even smaller seals.

Walruses can sleep in the water, their heads supported by an inflatable pouch which allows them to bob comfortably in the choppy near-freezing water. Additionally they change color with the temperature—their surface skin can be pink, as blood rushes near to the surface when they are hot, or they can turn grey brown when cold.

All pinnipeds, including walruses, are in the order Carnivora where they seem to most closely share a common ancestor with bears back in the Oligocene. Walruses are the only species in the only genus of the family Odobenidae. Once the Odobenidae were a sprawling family with at least twenty species spread across three several subfamilies (the Imagotariinae, Dusignathinae and Odobeninae), but something went wrong and walruses are all that’s left of the saber-toothed seals.

Walruses’ only natural predators are polar bears and killer whales, but even the world’s largest land predator and the most formidable ocean predator find adult walruses intimidating. Except in extraordinary circumstances the huge predators only hunt calves or weakened walruses. Predictably, humans are the walruses’ main problem. In the 18th, 19th, and 20th century immense numbers of walruses were killed for blubber, skin, meat, and ivory. Today this commercial exploitation has ended and worldwide populations have rebounded somewhat–though certain geographic areas remain depopulated.

Perhaps because they move ponderously on land and because their whiskers suggest comic uncles, some people underestimate walruses. I have been fortunate enough to see a young adult walrus in captivity (he was orphaned as a pup and would have died if not taken in by an aquarium) and it is a mistake to underestimate these animals. The walrus (whose name was Ayveq) was as large as a midsized truck, yet he could move with shark-like speed but ballet-like grace in the water. Bull walruses come into maturity at the age of 7, but they don’t usually get to mate with cows until they are 15 or so and have bested many competitors in savage sword duels with their tusks. Ayveq had access to a harem of walrus cows from a much younger age, and his comic attempts to understand himself and his relation to the females was a source of much surprised astonishment among aquarium-goers. As a peripheral point, I neglected to mention that male walruses have a uniquely large baculum which can measure up to 63 cm (25 inches)—larger than that of any other land mammal. The apparatus supported by this bone is similarly oversized.

Ayveq could produce a remarkable series of shrieks, grunts, whistles, bellows—apparently communication is important in the teaming masses of walrus colonies. Whether drinking herring through a straw, mugging for a crowd, or using his back flippers to amuse himself, Ayveq was always remarkable. His death saddened me considerably and I could not write about walruses without mentioning his extravagant personality. Knowing Ayveq also left me convinced that walruses might be perverts but they are also highly intelligent and gregarious beings. This conviction is born out by the painstaking work of biologists and zoologists who are just beginning to recognize how complicated walrus society is. It is no wonder, that so many poets, artists, and musicians have referenced the remarkable tusked creatures.