You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘pelagic’ tag.

Something which fascinates me is when a very successful species is so successful that it evolves away from its original habitat into a new niche. Examples of this literally make up the history of life on the planet, but today I want to talk about one of my favorite families of fish, Balistidae, the triggerfish, the cunning, clever, and truculent nast5ers of the coral reef environment. Except today we are writing about a triggerfish which left the colorful, frenetic cities of the coral reef and evolved to live in the vast open ocean. This is Canthidermis maculata aka “the spotted oceanic triggerfish”, a medium-sized triggerfish which has a worldwide distribution in temperate oceans from New York to London, down around the Cape of Good Hope and then across the Indian Ocean to the Gulf of Thailand. It can be found in the Pacific Ocean from Japan across to Hawaii and to the California and South American coasts.

The fish are silver or gray with little pale dots of blue or white. Although they can grow to half a meter (20 inches) in length, adults are more commonly 35 centimeters (14 inches) long. Reef triggerfish are opportunistic feeders and so, it seems are spotted oceanic triggerfish which can be carnivorous or planktivorous depending on the circumstances (although they seem to specialize in hunting smaller fish).

Like many pelagic fish (but unlike most other triggerfish) these fish seem to assemble in loose schools to travel the oceans. they are preyed on by sailfish, mahi-mahi, large sea birds, and other such predators (and by rapacious humans, of course). Female triggerfish build their nests in rough proximity on ocean bottoms from 4 meters to 45 meters deep where they guard and aerate the eggs (which hatch very quickly and disseminate the little larval fish throughout the oceans.

In all of entertainment, no figure is more beloved than Opah! Her networks make the most money. Her endorsements confer instant fame and wealth. Her personal life is the subject of profound fascination and scrutiny. She is what all Americans aspire to be…a veritable queen who transcends…

Wait…Opah? That’s a big orange fish! Also known as moonfish, opahs consist of two species (Lampris guttatus and Lampris immaculates) which are alone in their own small family the Lampridae. Their closest relatives are the magnificent ribbonfishes like the crestfishes and oarfish! They are discoid fish with orange bodies (speckled with white) and with bright vermillion fins. Opahs do not give away cars or support quack psychiatrists and physicians, but, they are much in the news right now anyway. To the immense surprise of ichthyologists and zoologists, a research team from the NOOA has discovered that Opahs are warm-blooded—in a way. They are the only endothermic fish known to science.

Being warm-blooded allows animals in the deep ocean to think and move more swiftly than the more ascetic and staid dwellers of the deep (most creatures of the ocean bottom are usually slow and placid in order to conserve energy–like the tripod fish). Ocean birds and marine mammals have long used this to their advantage. They gulp air from the surface and then dive deep to catch slower moving fish, squid, and invertebrates from the cold depths.

Other high-speed predatory fish (certain species of sharks and sportsfish) can warm key muscle groups using heat exchanging blood vessels in order to gain a burst of super speed, but these fish rapidly lose their heat—and the related speed advantages–as their blood circulates through their gills. This is one of the reasons sharks and marlins lunge and then return to slow measured swimming.

The opah appears to produce the majority of its heat by constantly flapping its pectoral fins. The warmth thus generated is not lost through the opahs’ gills. Critically, these fish possess unique insulated networks of blood vessels between their hearts and gills. The residual heat is removed from blood headed through the gills and then restored as it goes back through the heart. Their weird circular shape and comparatively large size are additional adaptations to help them conserve this warmth.

Marine biologists know surprisingly little about opahs (especially considering that the fish have long been known to fishermen and diners). Opahs live in the mesopelagic depths 50 to 500 meters (175 to 1650 feet) beneath the surface but it now seems they might make deeper hunting forays into the true depths. They are solitary hunters which live on shrimp, krill, and small fish. Opahs are approximately the size of vehicle tires. The smaller species (Lampris immaculatus) is like a big car tire and reaches a maximum of 1.1 m (3.6 ft). The larger species, Lampris guttatus, can become as large as an industrial lorry tire and can attain a length of 2 m (6.6 ft). the largest opahs weight up to 270 kg (600 lb).

Larval opahs resemble the larvae of oarfish (they are long and ribbonlike with strange protuberances. The main predators of Opahs are the great sharks…and humankind. Because of predation from this latter species which is endlessly hungry the survival of the opahs has grown less certain. It is believed that they have a low population resilience, but this…like their numbers and their lifestyle is unknown to science. We only just found they were warm-blooded earlier this month!

The Cranchiidae are a family of squid commonly known as “glass squid” which live in oceans around the world. The squid are of no interest to commercial fisheries (yet) and a great deal about this family remains completely unknown. Most of the 60 known species of cranchiidae are small and inconspicuous–indeed the majority are transparent and thus nearly invisible. However the largest known mollusk, the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni), is part of the family, (so it might be wise not to antagonize them on the playground).

Glass squid are notable for having stubby swollen-looking bodies and short arms except for one long pair of hunting tentacles. The majority of glass squid have bioluminescent organs which they use to hunt, to communicate and to disguise the faint shadows cast by their transparent bodies (predators of the deep can see even the faintest shadows cast by the dim light from the surface). The cranchiid squids themselves sport a variety of interesting and complex eyes which range from giant circular eyes to stalked eyes to telescoping eyes. This little gallery shows how delicate, diverse, and beautiful (and how utterly alien) these squid can be.

Juvenile cranchiid squid are part of the plankton and live near the surface where they hunt microscopic prey while trying to avoid thousands of sorts of predators. As they mature, they change shape and descend to deeper waters—indeed some species become practically benthic and can be found more than 2 kilometeres under the ocean. Glass squid move up and down the water column by means of a fluid filled chamber which contains an ammonia solution (which maybe explains why they are not on the human menu yet).

Today we have a special (but largely visual) treat: the pelagic octopus Vitrelladonella richardi. This cephalopod is “transparent, gelatinous, and almost colorless.” Since they are not only transparent but also live in the deeper part of pelagic zone of the ocean (the portion which is near to neither the top nor the bottom) they are rarely seen and little is known about them. The females are ovoviviparous and broods her eggs within her body. Both genders are strongly bioluminescent and use light for hunting, communicating, and hiding (by mimicking the faint light from the surface they can become even more invisible). Even if we don’t know a huge amount about these octopuses, we are privileged to have some amazing photographs of them, thanks to the new generation of submersibles and submersible drones, which are exploring the pelagic regions of the ocean. Look at how exquisite and alien these octopuses appear! It’s hard to believe we share the planet with such strange animals…

The world is a strange place filled with astonishing and bizarre animals. Among the strangest creatures are those which are transparent*—animals which barely seem to be there because the tissues that make up their bodies are permeable to light. There are transparent catfish, transparent insects, transparent crustaceans, and even transparent frogs (to say nothing of cnidarians, the majority of which are transparent!). Today’s post however concerns transparent mollusks. In addition to having transparent bodies some of these incredible invertebrates have transparent shells, can invert their bodies, or can glow. Check them out:

The Glass Squid (Teuthowenia pellucida) also known as the googly-eyed glass squid lives throughout the oceans of the southern hemisphere. The creature is about 200 millimeters (8 inches) long and has light organs on its eyes. Although transparent it has a bluish cast and it possesses the ability to roll into a ball or to inflate itself. These tricks do not always work and the little squid is frequently eaten by weird deep-sea fish and sharks.

Recently discovered in a huge cave system in Croatia, Zospeum tholussum, is a small delicate snail with a transparent shell.

This pterotracheid heteropod mollusk is a member of the Carinaria genus. It lives in the open ocean and flaps through the water scooping up plankton in a modified snail foot. Just as its snail foot has changed into a swimming/harvesting organ, the mollusk’s shell has shrunk into near nonexistence.

Above is an unknown pteropod (possibly of the genus Corolla), which was photographed near Oceanographer Canyon off the coast of Massachusetts.

Above is an unknown pteropod (possibly of the genus Corolla), which was photographed near Oceanographer Canyon off the coast of Massachusetts.

Vitrelladonella Richardi is a deepwater pelagic octopus found in tropical and subtropical waters around the world. The little octopus only measures 80cm (2.6ft) in length. Like many of these almost invisible mollusks very little is known about how it lives, but it is certainly beautiful in a very alien and otherworldly way.

*The author of this opinion piece is opaque. His opinion may not represent the larger community of organisms.

“Blanket octopus” sounds like an endearing nursery game, but the blanket octopuses are actually pelagic hunters which have adapted to living in the ultra-competitive environment of the open ocean. There are four species of blanket octopuses (Tremoctopus) which can be found ranging from the surface to medium depths of open tropical and subtropical seas worldwide. Because they often live far from any land, some of the methods which other octopuses use to escape predators do not work very well for them. Fortunately Blanket octopuses have adapted in their own unique bag of tricks.

Blanket octopuses are named after the distinctive appearance of adult female octopuses which grow long transparent/translucent webs between their dorsal and dorsolateral arms. Blanket octopuses use these webs as nets for hunting fish, but they can also unfurl and darken their nets in order to appear much larger than they actually are. Since blanket octopuses do not produce ink and can not camouflage themselves as rocks, coral, or sand, they rely heavily on their blankets. As a last resort they can jettison the blankets as a decoy and jet away while the confused predator attacks the highly visible membranes.

Blanket octopuses exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism. Whereas the female octopus can grow up to 2 meters (6 feet) in length, the male octopus is puny and does not grown longer than a few centimeters (1 to 2 inches). Males store their sperm in a modified quasi-sentient third right arm, known as a hectocotylus. During mating this arm detaches itself and crawls into the female’s reproductive vent. As soon as the hectocotylus is detached the male becomes unnecessary and dies.

Tiny males and immature females do not have blankets, but they utilize another trick to protect themselves. Because they hunt jellyfish and other hydrozoans, the little octopuses are immune to the potent venom of the Portuguese man o’war. The octopuses tear off stinging tentacles from the man o’war and wield them in their tentacles like little whips to ward off predators.

The Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) is not a jellyfish, in fact it is not a discreet animal at all, but instead a siphonophore—a colonial medusoid made up of specialized animal polyps working together as an organism. These siphonophores have stinging tentacles which typically measure 10 metres (30 ft) in length but can be up to 50 metres (165 ft) long. Being stung by a man o’ war does not typically cause death, but sailors and mariners who have survived the experience assert that it taught them a new definition of agony.

But the fearsome man o’ war is not the subject of this post. Instead we are concentrating on the animal which feeds on the man ‘o war (as well as other siphonophores which drift in the great blue expanses of the open ocean). One is inclined to imagine that men o’ war are eaten only by armored giants with impervious skins and great shearing beaks (and indeed the world’s largest turtles, the loggerheads, are the main predators of siphonophores), however another much less likely predator is out there in the open ocean gnawing away at the mighty stinging colonies. Glaucus atlanticus, the blue sea slug, is a tiny shell-free mollusk which lives in the open ocean. The little nudibranch only grows up to 3 cm in length but it hunts and eats a variety of large hydrozoans, pelagic mollusks, and siphonophores (including the man o’ war).

Although not quite as gaudy as its lovely cousins from tropical coral reefs, Glaucus atlanticus is a pretty animal of pale grey, silver, and deep blue with delicate blue appendages radiating out from its six appendages. The little mollusks live in temperate and tropical oceans worldwide. They float at the top of the water thanks to a swallowed air bubble stored in a special sack in their gastric cavity. Because of this flotation aid, the slug is able to cling upside down to the surface tension of the waves. Since it is entirely immune to the venomous nematocysts of the man o’ war, the sea slug can store some of the man o’ wars venom for its own use. The tendrils at the edge of Glaucus atlanticus’ body can produce an extremely potent sting (so it is best to leave the tiny creatures alone, if you happen to somehow come across them).

Each and every Glaucus atlanticus is a hermaphrodite with a complete set of sex organs for both genders. Incapable of mating with themselves they ventrally (and thoroughly) embrace another blue sea slug during breeding, and both parties then produce strings of eggs. The hatchling nudibranchs have a shell during their larval stages, but this vestige quickly disappears as they mature into hunters of the open ocean.

I’m going to take a break from the topic of catfishes to post an overview of the lovely and mysterious oarfish. This topic also serves as an appropriate follow-up to a previous post concerning the largest fish ever, for, in the present era, Oarfish are either the longest bony fish in the world or the longest fish outright (depending on the source). The Guinness Book of Records recorded a specimen of the oarfish Regalecus glesne which measured 17 meters (56 feet) long. If correctly recorded, that fish’s length surpassed the length of the largest confirmed whale shark–which was 12.65 metres (41.50 ft) long. However Regalecus glesne specimens more usually measure 11 meters or less. Other species of oarfish do not attain such great sizes: Regalecus russelii usually measures a maximum of 5.5 meters and Agrostichthys parkeri, the streamer fish, seldom exceeds 3 meters.

I’m going to take a break from the topic of catfishes to post an overview of the lovely and mysterious oarfish. This topic also serves as an appropriate follow-up to a previous post concerning the largest fish ever, for, in the present era, Oarfish are either the longest bony fish in the world or the longest fish outright (depending on the source). The Guinness Book of Records recorded a specimen of the oarfish Regalecus glesne which measured 17 meters (56 feet) long. If correctly recorded, that fish’s length surpassed the length of the largest confirmed whale shark–which was 12.65 metres (41.50 ft) long. However Regalecus glesne specimens more usually measure 11 meters or less. Other species of oarfish do not attain such great sizes: Regalecus russelii usually measures a maximum of 5.5 meters and Agrostichthys parkeri, the streamer fish, seldom exceeds 3 meters.

A 23-foot long Oarfish that washed up at the Naval Training Center, Coronado Island, Calif, September 1996.

Oarfish are solitary animals which live deep in the pelagic zone of the ocean (the pelagic zone is the part of the ocean which is neither close to the shore nor to the bottom). They swim through the great open waters of the oceans frequenting depths of about 200 meters–although they lack a swim bladder and may sometimes swim much deeper into the abyssal portions of the ocean. Like many other ocean giants, oarfish are filter feeders and subsist on zooplankton, tiny crustaceans, and the occasional jellyfish, or squid. Because their regular habitat is so remote for humans, oarfish are seldom seen at all (and those that do get spotted are usually sick, dying, or dead). In days before the internet, their rarity provided fodder for tragicomic tales of yokels mistaking them for sea serpents. Oarfish are covered with irregular blue and black squiggles which fade when they die, as does their silver iridescence. In addition to their great length, oarfish are notable for their beautiful red and pink dorsal fins. The first few rays of these fins are very long and give the fish the appearance of wearing a crown (hence the family name Regalecidae—the regal ones). Oarfish obtained their common name from the mistaken belief that they “rowed” through the water using their elongated pelvic fins. The fish actually move by undulating body-length dorsal fins. Six species of oarfish are known to science, although the creatures are so rarely encountered that undiscovered species or genera may exist.

A rare photo of a live oarfish. Oarfish are known to orient themselves vertiically in this manner--perhaps to search for food.

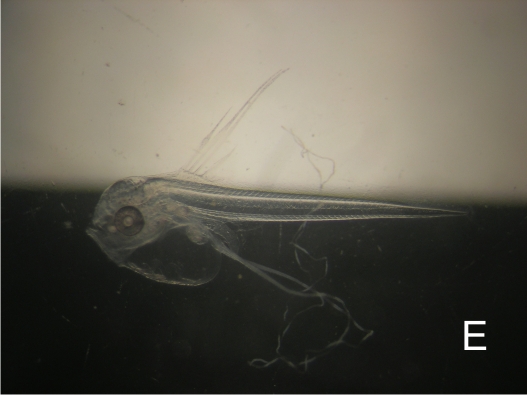

Like many teleosts, oarfish go through a larval stage immediately after they hatch from the egg. During this time the tiny transparent fry possess an appearance greatly different from their adult counterparts. They hunt among the zooplankton which they gobble up with extensible mouths. Nothing is known of how oarfish spawn. It is also not known how long they live or what their habits are in the great blue expanses of the ocean.