You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘revolution’ tag.

I wanted to share with you a glimpse back into history to one of the most peculiar and specialized cities of western history. During the middle ages, monasticism was a vast and powerful cultural force. Indeed, in certain times and places, it may have been the principal cultural force in a world which was painfully transforming from the slave society of classical antiquity into the modern kingdom states of Europe.

West of the Alps, the great monastic order was the Benedictine order, founded by Saint Benedict of Nursia, a Roman nobleman who lived during the middle of the 6th century. “The Rule of Saint Benedict” weds classical Roman ideals of reason, order, balance, and moderation, with Judeo-Christian ideals of devotion, piety, and transcendence. The Benedictine Order kept art, literature, philosophy, and science (such as it was) alive during the upheavals of Late Antiquity and the “Dark Ages”–the brothers (and sisters) were the keepers of the knowledge gleaned by Rome and Greece. The monks also amassed enormous, wealth and power in Feudal European society. The greatest abbots were equivalent to feudal lords and princes commanding enormous tracts of land and great estates of serfs.

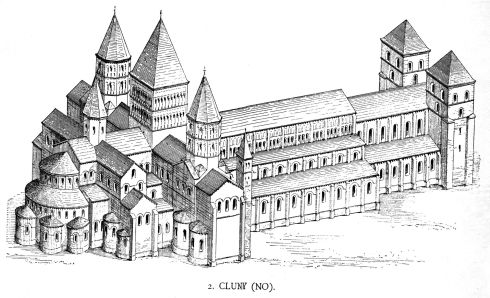

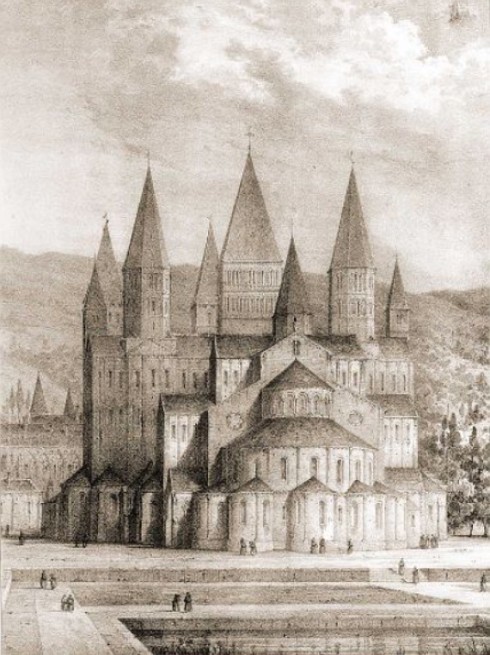

Nowhere was this more true than in Cluny, in east central France (near the Swiss Alps), where Duke William I of Aquitaine founded a monastic order with such extensive lands and such a generous charter that it grew beyond the scope of all other such communities in France, Germany, northern Europe, and the British Isles. The Duke stipulated that the abbot of the monastery was beholden to no earthly authority save for that of the pope (and there were even rules concerning the extent of papal authority over the abbey), so the monks were free to choose their own leader instead of having crooked 2nd sons of noblemen fobbed off on them.

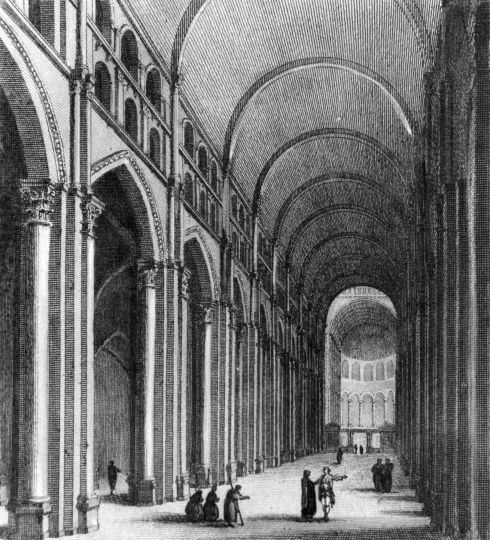

Additionally, the monastery created a system of “franchise monasteries” called priories which reported to the authority of the main abbot and paid tithes to Cluny. This wealth allowed Cluny to become a veritable city of prayer. The building, farming, and lay work was completed by serfs and retainers, while the brothers devoted themselves to prayer, art, scholarship, and otherworldly pursuits…and also to politics, statecraft, administration, feasting, and very worldly pursuits (since the community became incredibly ric)h. The chandeliers, sacred chalices, and monstrances were made of gold and jewels, and the brothers wore habits of finest cloth (and even silk).

The main tower of the Basilica towered to an amazing 200 meters (656 feet of height) and the abbey was the largest building in Europe until the enlargement of St. Peter’s Basilica in the 17th century. At its zenith in the 11th and 12th century, the monastery was home to 10,000 monks. The abbots of Cluny were as powerful as kings (they kept a great townhouse in Paris), and four abbots later became popes. At the top of the page I have included a magnificent painting by the great urban reconstruction artist, Jean-Claude Golvin, who painstakingly reconstructs vanished and destroyed cities of the past as computer models and then as sumptuous paintings. Just look at the scope of the (3rd and greatest) monastery and the buildings around it.

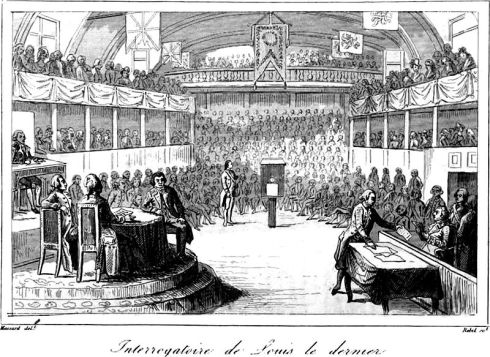

Such wealth also engendered decadence and corruption. Later abbots were greedy and incompetent. They oppressed the farmers and craftspeople who worked for them and tried to cheat the merchants and bankers they did business with. The monastery fell into a long period of decline which ended (along with the ancien regime, about which similar things could be said) during the French Revolution. Most of the monastery was burnt to the ground and only a secondary bell tower and hall remain. Fortunately the greatest treasures of Cluny, the manuscripts of the ancient and the medieval world, were copied and disseminated. The most precious became the centerpiece of the Bibliothèque nationale de France at Paris, and the British Museum also holds 60 or so ancient charters (because they are good at getting their hands on stuff like that).

We can still imagine what it must have been like to live in the complex during the high middle ages, though, as part of a huge university-like community of prayer, thought, and beauty. it was a world of profound lonely discipline tempered with fine dining, art, and general good living–an vanished yet eternal city of French Monastic life.

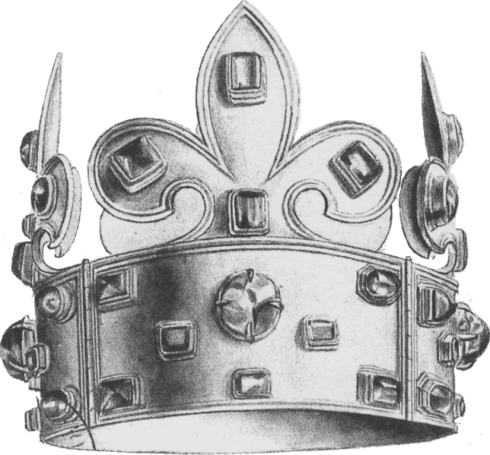

I enjoy putting up pictures of amazing historical crowns glittering in heavily guarded vaults in countries which are now democracies, yet the crowns which have disappeared are often more interesting even to the point of being allegorical. An example of this is the crown of George XII of Georgia. His highly traditional arched crown of red velvet, gold, and jewels looked like the crown from a high school play or on a corporate logo. It was manufactured by were promptly manufactured by the artist Pierre Etienne Theremin and the goldsmith Nathanael Gottlob Licht in St. Petersburg. The crown was made in 1798 and, when George XII died in 1800 the crown (and Georgia) were duly annexed by Paul I and Alexander I. The crown was kept in the Kremlin until the communist revolution. After the communists took full control of the country, the crown was returned to Georgia in 1923. Unfortunately, it was an age of exigency, and the communist leaders of Georgia decided to “use” the crown in 1930 (whereupon it disappears entirely from history). The two equally likely fates of the crown are both interesting in a choose-your-own adventure sort of approach to political hegemony. In one scenario, the crown was broken up by the Georgian communists and the constituent gold and jewels were sold (or purloined). In an equally plausible fate for the crown, it was sold to super-rich oil titan Henri Deterding, the erstwhile head of Royal Dutch Shell. If this latter case is true, the crown could still be in the private collection of some super-rich collector, who has no need to advertise the fact he has the crown (or possibly doesn’t even know what it is). I wonder which of these possible fates befell the crown…or did something altogether different happen? Anyway, if you happen to have it in a box in your attic, you should call somebody, it may be worth something and I bet the Georgians would love to have it back.

Emperor Dom Pedro I at age 35, 1834

One of the founding fathers of Brazil’s democracy was, somewhat ironically, a king and a colonial emperor. Born in 1798, Dom Pedro I was the fourth son of King Dom João VI of Portugal and Queen Carlota Joaquina. When Portugal was invaded by the French in 1807, the royal family fled to the wealthy and vast Portuguese colony of Brazil. Young Pedro thus grew up on the vast estates of South America. The prince particularly enjoyed physical and artistic pursuits such as hunting, building, music, furniture making, and horseback riding (although he tended to neglect his academic pursuits and studies in statecraft). When he reached adolescence he pursued other physical pursuits as well, and his romantic dalliances were a lifelong problem for his government and his wife, Maria Leopoldina, an Austrian Princess.

In 1821, revolution in Portugal compelled Dom João VI to return to Lisbon. The king left his son Pedro as regent…he also left some valuable advice: if revolution were to come also to Brazil (a certainty in those days of colonial independence), Pedro should join it, rebel against his father and co-opt the movement for himself. This is exactly what Pedro did in 1822. On the 1st of December, 1822, Pedro became Pedro I, the first Emperor of Brazil. By 1824 the huge South American nation had made a clean break from Portugal and was well and truly independent.

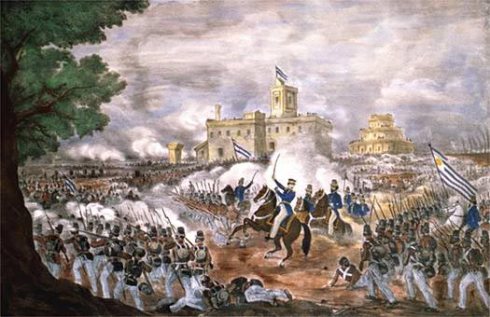

Declaration of Brazil’s independence by Prince Pedro on 7 September 1822

Declaration of Brazil’s independence by Prince Pedro on 7 September 1822

Alas, Pedro’s constitutional empire was ridden with secessionists. Brazil swiftly began to rip apart into separate nations. First he was forced to quash the Confederation of the Equator, a secession bid in Brazil’s northeast. Then he had to fight the Cisplatine War, an Argentine land grab which ultimately lead to an independent Uruguay being carved out of Brazil’s southernmost province.

Pedro I was the heir apparent to the Portuguese throne (which he rebelled against back up in paragraph 2). When his father died in 1826, he briefly became king of Portugal before abdicating that throne in favor of his daughter, Dona Maria II. Unfortunately his scheming younger brother, the traditionalist Dom Miguel, stole the throne from his niece (Dom Pedro had toyed with the idea of marrying them in order to prevent exactly such an outcome). Weary of secession attempts, and recognizing that he was needed back in Portugal, Pedro I abdicated in favor of his 5 year old son Pedro II. He joined forces with the Portuguese liberals and defeated his brother in an Iberian civil war, but just as this “War of Restoration” was finished he keeled over from tuberculosis.

Among all of those revolutions, counter-revolutions, abdications, and trans-Atlantic crossings, it is easy to lose sight of how remarkable Pedro I was. In an age of bondage, he despised slavery. Unable to convince the slaveholding landowners of the Brazilian national assembly to enact a gradual process for ending slavery, he decided to lead by example and freed all of his slaves. He then granted lands from his estate at Santa Cruz to these manumitted bondsmen.

He possessed an understanding of people’s shared humanity. This is rare enough among everyone but especially unusual among those who are born to immense privilege. When adoring Brazilians once unyoked the horses of his carriage and began pulling it themselves, he promptly stopped them and proclaimed “It grieves me to see my fellow humans giving a man tributes appropriate for the divinity, I know that my blood is the same color as that of the Negroes.”

After Dom Pedro’s day, Brazil has sometimes flirted with absolutism (always to its detriment), however the delightfully heterogeneous and chaotic modern democracy owes its real character to this king who was always willing to set aside his own power, prestige, and privilege in order to advance the betterment of all.

*Also, apparently, his grooming was immaculate. It is a footnote, but everything I have read mentions it.

I need a job! If any of you folk out there need a writer/toymaker/artist/analyst let me know. I will work for you with unflagging fervor, intellect, and creativity. I only need a smidgen of money for catfood and rent (and someone else to manage the spreadsheet)!

Sadly, according to the want ads I have been looking at, the world does not want astonishing super creativity. Right now, the market economy only wants these infernal i-phones and tablets which everyone is looking at all the time. The majority of jobs available are for low-level sales-clerks and admins to staff humankind’s great transition into a fully functional hive mind (where we humans, the individual neurons, are all always networked together through our androids and blackberries).

I’m no Luddite. I enjoy technology and I can imagine great benefits arising from the internet when it fully grows up into a vast colony-mind. Yet, so far iphones mostly provide a solipsist diversion—or, at best—a platform for buying and selling more unneeded junk or channeling resources to Carlos Slim and other anointed telecom winners. Naturally, I exempt Wikipedia from this grumpy jeremiad—it is indeed an amazing realization of the great utopian dreams of the Encyclopedists. I suppose I should exempt this very blog and you, my cherished readers, as well… but, after a day of looking at ads for junior marketing interns and assistant admin assistants, I can’t entirely. Here I am creating “content” for free so some MBA higher up the tech food chain can point at an infinitesimal rise or fall on a bar chart while his colleagues clap him on the shoulder and talk of “synergies.” I certainly don’t want to be that guy either! But what else is there? What are we supposed to do?

To escape these circular author-centric thoughts, let’s take a field trip around the world. To provide a more comprehensive vision of the smart phone revolution, today’s post takes us to Inner Mongolia—the vast landlocked desert hinterland of China. There, amidst the lifeless dunes and the alkaline sink holes is a vast manmade lake—Lake Baotou—which reflects some of the complicated dualities of the globalized market and the technology revolution. It has been said that each computer screen and cellphone window is a “black mirror” where we watch ourselves. Lake Bautu is a different sort of black mirror. It is literally a layer of super-toxic black sludge which is left over when the rare-earth elements and heavy metals necessary for smart phones have been processed.

Ferrebeekeeper has visited the world’s biggest lake, and we have dipped our toes into the fabled waters of Mount Mazama where the Klamath spirit of the underworld dwells. We have visited Lake Lonar where a space object slammed into the black basalt of a long dead shield volcano, and we have even been to China’s biggest lake where the world’s largest naval battle took place. However, Lake Baotou is a whole different manifestation of the underworld. Sophisticated modern electronics require cerium, neodymium, yttrium, europium, and goodness only knows what else. These so-called rare earth elements are also necessary for wind turbines, electric car arrays, and next generation green technologies.

Yet the refinement process for these elements is unusually corrosive and toxic and the waste products are horrifying. The raw materials tend to be found in great evaporitic basins (like those of Inner Mongolia, where an ancient ocean dried into vast dunes) but most nations are wary of processing these materials because of the unknown long-term cost. China’s leaders recognized the economic (and defense!) potential of becoming the world’s main (only?) supplier of these esoteric elements and the end result has been cheap consumer electronics, a communication revolution…and Lake Baotao, which slouches dark and poisonous beneath the refining towers and smokestacks of Baotao City.

On the plus side, Baotao (pictured here during rush hour) is evidently the bicyclists’ paradise I was wishing for last week!

A former roommate of mine visited Inner Mongolia and walked the streets of Baotao City. He described a wild-west boomtown filled with brothels, bars, Mongolian barbeque places, and…cell phone stores! Crime and excess were readily apparent everywhere as were prosperity and success—like old timey Deadwood or Denver. I wonder if Baotao City will develop into a modern hub like Denver or Chicago, or will it disappear back into the thirsty dunes when this phase of the electronics boom is over (or when its effluviums become insuperable).

In the mean time we all have to flow with the shifting vicissitudes of vast entwined global networks. We must make ends meet in a way which hopefully doesn’t harm the world too much. Now I better get back to scouring the want ads! Keep your eyes open for a job for me and please keep following me, um, on your computers and smart phones…

The Crown of Charlemagne, the coronation crown of French Kings for nearly a millenium (shown without cap)

From the era of Frankish Kings until the French Revolution, the kings of France were crowned with the so-called Crown of Charlemagne, a circlet of four gold rectangles inset with jewels. The crown was made for Charles the Bald, the Holy Roman Emperor who lived in the ninth century (who apparently needed an ornate head covering for some unknown reason). Four large jeweled fleur-de-lis were added in the late twelfth century along with a connecting cap ornamented with gems. A matching crown for the queen of France was melted down by the Catholic League in 1590 when Paris was besieged by the Protestant king Henry IV (before he was, you know, stabbed to death by a zealot when the royal carriage was stuck in traffic), yet the crown of Charlemagne survived France’s religious wars & was used in coronations up until 1775 when Louis XVI was crowned. The crown vanished during the French revolution and has never been seen since. A certain Corsican monarch crafted a replacement: the second Crown of Charlemagne was completely different and will be the subject of a subsequent post.

Ned Ludd was a person with severe developmental problems back in the 18th century, when society lacked effective ways of assisting people with disabilities. In the cruel parlance of the time he was a “half-wit”. Supposedly, Ned worked as a weaver in Anstey (an English village which was the gateway to the ancient Charnwood forest). In 1779, something went wrong—either Ned misunderstood a confusing directive, or he was whipped for inefficiency, or the taunts of the villagers drove him to rage. He picked up a hammer and smashed two brand new stocking frames (a sort of mechanical knitting machine used to quickly weave textiles). Then he fled off into the wilderness where he lived as a freeman. Some say that in the primal forests he learned to become a king.

Ned is important not because of his life (indeed it seems likely that he was not real—or, at best, he was just barely real) but because he was mythicized into a larger-than-life figure around whom the Luddite movement coalesced. This diffuse social rebellion had some roots in the austere and straightened times of the Napoleonic war but it was mostly a direct response to the first sweeping changes wrought by the Industrial revolution. Skilled weavers and textile artisans were aggrieved that machines operated by unskilled workpeople could easily produce much more fabric than trained artisans using traditional methods. The unskilled workpeople were angry at being underpaid and mistreated in the harsh dangerous early factories. This anger was combined with widespread popular discontent about the privations of war and the rapacity of the elite. Free companies of rebels met and drilled at night in Sherwood Forest or on vacant moorland. Anonymous malefactors smashed the new machines. Mills burnt down and factory owners were threatened. It was whispered that it was all the work of “King Ludd” whose rough signatures appeared on broadsheets and threatening letters.

The first wave of Luddite Rebellion broke out in 1811 centered in Nottingham and the surrounding areas. It is interesting that the same region which came up with Robin Hood, the hero-thief of folklore, also was responsible for remaking Ned Ludd from a lumpen outsider into a bellicose king of anti-technology. Disgruntled (male) artisans marched in women’s clothes and called themselves “Ned Ludd’s wives”. Circulars were addressed from the “king’s” office deep in Sherwood forest.

The original teasing tone quickly vanished as Luddite uprisings broke out across Northern England in the subsequent months and years until British regulars were sent in to quash them. For a brief period, there were more redcoats putting down Luddite insurrections in England than there were fighting Napoleon on the Iberian Peninsula. Professional soldiers made short work of the rebels and Parliament hastily enacted a series of laws which made “machine-breaking” a capital crime. A number of Luddites were executed and others were transported to Australia.

Ned Ludd escaped these reprisals by being from a different era (and fictional). “Luddite” has now become a preferred label for all people who eschew technology. The half-wit King Ned still lives on in the imagination of people who have lost their jobs to the march of progress and in the nightmares of technophiles and economists. Indeed one of the great constructs/truisms of economics is the Luddite fallacy—which holds that labor saving devices increase unemployment. Neoclassical economists (who named the concept) assert that it is a fallacy because labor saving devices decrease the cost of goods—allowing more consumers to obtain them. However there are some who believe this has only been the case so far because the machines have not become sophisticated enough. Once a certain threshold of technology is passed thinking machines might replace many skilled positions as well as unskilled ones. This simultaneously awesome and horrifying concept will be our theme tomorrow.