You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Qing’ tag.

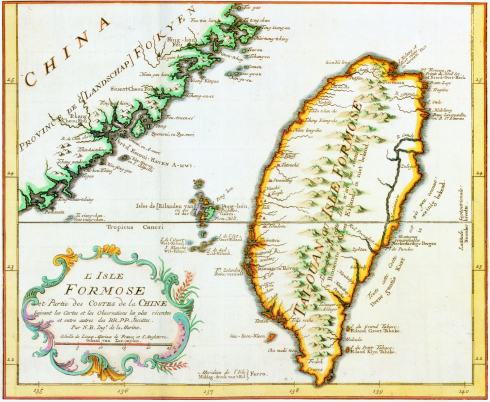

Zhu Yigui was a Fujianese duck farmer who lived in Formosa (now Taiwan) during the 18th century. He was said to command his ducks with martial precision: according to legend, he even trained his ducks to march in military formations like soldiers (although mother ducks have long mastered the same feat with their ducklings–so perhaps Zhu’s soldierly duck-training prowess was less illustrious than legend would make it seem). In 1721 an earthquake rocked the island and caused extensive damage. Some people lost everything. The imperial prefect of Formosa was not interested in hearing excuses and levied punitive taxes on the peasantry—even though smallholders were trying to cope with disastrous losses from the earthquake.

Unable to put up with this abuse from the incompetent Qing authorities, the people rose in rebellion. When they were looking for a leader they remembered the duck-raising prowess of Zhu Yigui who thus became a general. On the 19th of April of 1721 he attacked and captured the city of Gangshan. Soon other rebel factions joined the rebellion, as did the oft-abused aboriginal people of Formosa. Zhu Yigui was given the sobriquet “Mother Duck King.” His forces went on to capture Tainan, the island’s capital without even fighting.

Unfortunately, Zhu’s mastery over ducks did not adequately prepare him for dealing with rebels. He quarreled with his fellow rebel captains just as the Machu relief army was landing on Formosa. The rebels fell apart in pitched battle with professional soldiers and Zhu Yigui was captured and executed. Because of these troubling events duck farming was prohibited in Central Taiwan for many years. Still, whenever one compiles a list of illustrious duck-breeders from the Qing dynasty, Zhu’s name is certainly on the list!

In 1837, the American financial system melted down and took the United States into a horrible economic death spiral. In the same year, on the other side of the world, an obscure Chinese peasant named Hong Huoxiu had a nervous breakdown because he failed to pass the imperial civil service examinations (which only one out of a hundred test-takers passed anyway). Strangely enough, Hong’s private meltdown ultimately proved far more damaging to humanity than the collapse of the entire U.S. banking system. The ramifications of Hong’s actions are still being felt (and still being interpreted), but what is certain is that he was directly responsible for the deaths of 20 to 30 million people.

Hong Huoxiu was born the third son of a poor Hakka farmer in Guangzhou, Guangdong in 1814. He proved to be an apt scholar who had a way with words and concepts and, more importantly, an ability to memorize the Confucian classics which were the subject of the all-important imperial exams (which determined one’s status in life). His family tried to support him in his studies, and he came in first at the local preliminary civil service examinations, however he failed the actual imperial examinations four times (the exams at the time were very difficult, but they were also corrupt—and many people passed thanks to gold rather than correct answers). After failing for the fourth time, Hong fell into a serious illness and was tormented by bizarre dreams in which he traveled to the sky to meet a wise father figure and a powerful elder-brother dressed in a black dragon robe. Because of this dream epiphany, Hong changed his name to Hong Xiuquan (at the behest of the figures in his dreams). He stopped studying for the exam and became a tutor.

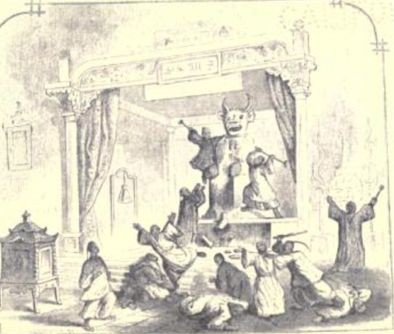

For six years thereafter, Hong scraped by, trying to understand the strange figures and portents from his delirium. He read and reread some tracts which had been given to him by Christian missionaries, and suddenly everything came clear to him in a startling revelation: the authority figure from his dreams was the Judeo-Christian god and the respected elder brother was Jesus. Hong realized that he was Jesus’ younger Chinese brother. Armed with this knowledge, he began to gather disciples and converts among the poor Hakka charcoal burners of Guanxi. In 1847, he made a formal study of Christianity and the Old Testament (which, not surprisingly, cemented his belief in his own divinity). Hong preached a strange mixture of communal sharing, Christian evangelism, and fiery rebellion. He had two immense symbolic swords forged (for the purpose of sweeping corruption and heresy out of China) and he burned Taoist and Budhhist books wherever he went.

In most other times, nobody would have paid attention to Hong (or the secret police would have noted him and dealt with him in a peremptory fashion), however in mid nineteenth century China the situation was ripe for millenarian craziness and fraudulent prophets. The corrupt Qing dynasty was floundering badly as crooked ministers feuded with each other and robbed the treasury. Famine and disaster stalked the land while bandits and rebellions popped up everywhere. The Western powers were openly squabbled over zones of influence within China. Opium addiction, religious extremism, and nihilism were popular panaceas. Against this horrible backdrop, the imperial government did not notice Hong until he had gathered 30,000 followers. In 1850, they dispatched a small army to dispense his followers, but by then it was too late. The imperial army was defeated and Hong’s forces executed the Manchu commander. The rebellion had begun in earnest: on January 11, 1851, Hong proclaimed the founding of the “Heavenly Kingdom of Transcendent Peace”. He assembled armies which he put in command of family and favorites and began conquering southern China in the name of a communal theocratic state.

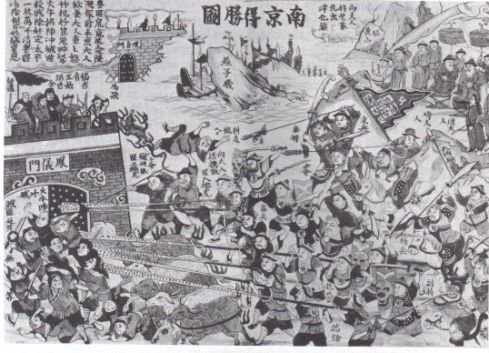

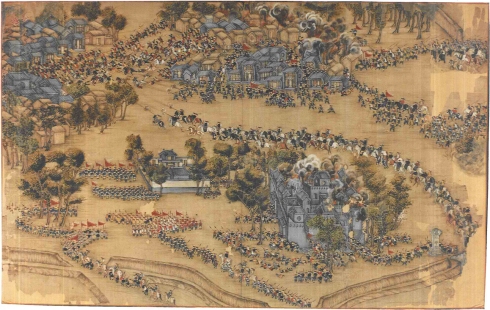

Scroll painting from “Ten scenes recording the retreat and defeat of the Taiping Northern Expeditionary Forces,February 1854-March 1855.”

The subsequent Taiping rebellion—a civil war between the Qing dynasty and the Heavenly Kingdom of Transcendent Peace—was one of the most destructive conflicts in history. At the height of the movement the Taiping rebels controlled 30 million subjects. As huge armies clashed, tens of millions of people were uprooted. Famine and disease became universal and the great cities of southern China were repeatedly besieged and burned.

The increasingly unstable Hong Xiuquan was a distant and hypocritical king to his strange and mismanaged kingdom. By 1853 he had withdrawn from day-to-day control of his kingdom’s policies and administration. He became an isolated quasi-divine figurehead who ruled through written proclamations and strange religious pronouncements (while being carried from palace to palace in a sedan chair born by beautiful concubines). For eleven years, his generals, prophets, and revolutionary figureheads fought an internecine war with imperial China, which only came to an end when the United Kingdom became involved and sent gunboats and British officers to assist the Emperor (most famously, Charles Gordon, a British military adventurer who went on to have one of the nineteenth century’s most colorful and infamous careers). Lead and organized by Gordon and by General Tso (who is forever memorialized as a sweet-sour chicken dish), the imperial forces who were ironically renamed “the ever-victorious army” finally crushed the Taiping rebellion in 1864.

Reclining amongst his dozens of wives and hundreds of concubines, Hong is said to have taken poison (or perhaps he died of eating noxious weeds—in accordance with a religious vision). Whatever the case, the Taiping rebellion was at an end. Thanks to a decade and a half of brutal fighting, southern China was devastated: huge piles of rotting corpses were littered throughout the Yangtze valley. Jesus’ Chinese brother, a nobody with a messiah complex, was directly responsible for one of the most violent and senseless incidents in history. By some accounts, he personally outdid the destruction caused by World War I.