You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘language’ tag.

OK, Last week was egg week here at Ferrebeekeeper where we looked at home-made egg-art and astonishing primordial mythology. Unfortunately, due to budget constraints and temporal vicissitudes, egg week only had 4 posts—yet we also need to keep moving on. Today’s post is therefore somewhat egg-themed….even if the real theme is more about the changing nature of language. It is a bridge from past to future—but a humorous one which has eggs at its center.

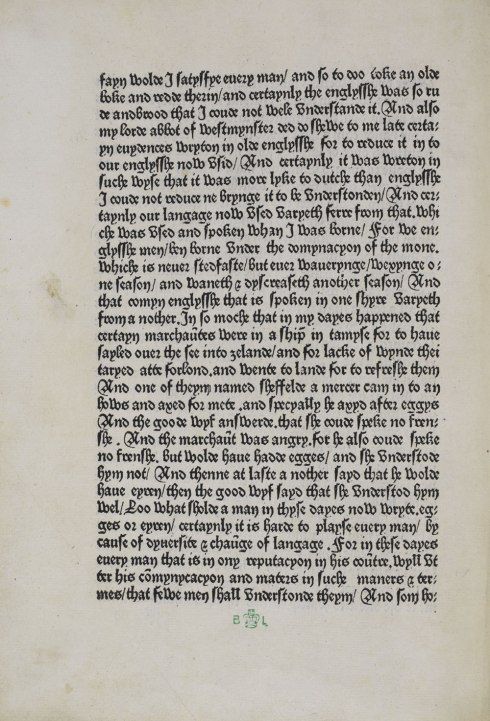

Here is a story from the late 15th century, when English was changing from Middle English to Modern English. The author, William Caxton, was a merchant, diplomat, and writer…and probably England’s first printer. He wrote this story in 1490 to marvel at how quickly the language was changing (indeed he relates how he can’t understand truly old English which seems like a completely foreign tongue). I have transcribed the story, as best I could, from the Gothic black letter manuscript (try reading some of the beautiful—but incomprehensible–Gothic calligraphy and I think you will appreciate my effort).

The story is a vignette about how language changes, seemingly on its own. This point is particularly poignant to modern readers who don’t speak with quite the same idiom and usage as the upstanding William Caxton! The story is about some merchants from the north who say eggs in the Norse fashion “eggys” as opposed to the South English way of saying it “eyren.” Misunderstanding ensues. It is interesting to note that contemporary English speakers talk about “eggs.” If I went to the C-town and asked for “eyren” they would probably look at me funny (or tell me where to get an iron or Irish whiskey). The Norse word for “eggs” clearly won out over the old Anglo-Saxon word when English went global. Anyway, here is my transcription of the story. Kindly help me out if you can figure it out better and enjoy the eyreny…err…the irony of Caxton’s words:

Fayn wolde I satysfye every man, and so to doo toke an olde boke and redde therin and certaynly the englysshe was so rude and brood that I could not wele understande it.

And altho my lord abbot of Westmynster ded do shewe to me late certain evydences wryton in olde englysshe for to reduce it in to our englysshe now usid.

And certainly it was wrton in suche wyse that it was more lyke to dutche than englysshe.

I could not reduce ne brynge it to be understonden.

And certaynly our language now used Uaryeth ferre from that. Which was used and spoken whan I was borne.

For we englysshe men ken borne under the domynacyon of the mone.

Which is neuer stedfaste, but ever waverynge wexynge one season and waneth & dycreaseth another season

And that comyn englysshe that is spoken in one Shyre varyeth from a nother.

In so moche that in my dayes happened that certayn marchauntes were in a ship in tamyse for to have sayled over the see into zeland

and for lacke of wynde they taryed atte Forrlonth, and wente to lanthe for to refreshe them

And one of them named Sheffelde a mercer cam in to an hous and axed(!!) for mete, and specyally he axyd after eggys.

And the goode wyf answerde that she could speke no frenche.

And the marchant was angry for he also could speak no Frenche but wolde have egges and she understode hym not.

And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde have eyren then the good wyf sayd that she understood hym wel

Loo (?) What sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte egges or eyren, Certaynly it is harde to playse every man that is in any

reputacyon in his contre. Wyll utter his comynycacyon and maters in suche maners & terms that fewe men shall understonde theym…

The Boa people (AKA Baboa, Bwa, Ababua) live in the northern savannah region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Today, as in the past, the majority of Boa make a living by hunting, fishing, and subsistence farming. They speak a Bantu language which shares the same name(s) as their tribe. The Boa once had a reputation as fearsome warriors. When Azande spearmen from southern Sudan invaded Boa lands during the nineteenth century, the Boa successfully repelled the invasion. Subsequently, in 1903 the Boa rebelled against Belgian colonial occupation. Even though they were woefully underequipped and poorly armed, the warriors stood up to the industrialized Belgian forces for seven years. After the rebellion, extensive missionary proselytizing caused the tribe to convert to Christianity.

The Boa are internationally famous for making exquisite wood carvings—particularly eerily beautiful masks and harps with human faces. Original carvings from the pre-Christian era are especially rare and precious. These works usually portray ferocious faces painted with black and white checkerboard patterns. Sadly, the ritual meaning of such masks is now unclear–presumably they were sacred to secret societies or used in the magical/religious ceremonies of warrior cults. Since the original religious cultural context is lost, we are forced to regard these masks solely as art objects—and what spectacular art they are! The mysterious black and white patterns, the feral mouths, and the delicately carved owl-like faces all point to a syncretism between humankind and the wider living world. The animistic masks symbolize not just the spiritual forces of the living animals and plants but also the forces of the night, the river, the weather, the ancestors, and the underworld. To put on such a mask would be to subsume oneself in a vast spiritual totality—to convene with vast forces beyond the purview of a single human life…maybe…or maybe they had an entirely different meaning to their makers. They are a beautiful dark enigma.

This week is Etruscan week here at Ferrebeekeeper—a week dedicated to blogging about the ancient people who lived in Tuscany, Umbria, and Latium from 800 BC until the rise of the Romans in 300 BC (indeed, the Romans may have been Etruscan descendants). Happy Etruscan Week! The Etruscans were known for their sophisticated civilization which produced advanced art, architecture, and engineering. In an age of war and empires, they were, by necessity, gifted warriors who fought with the Greeks, Carthaginians, and Gauls. They won wars, captured slaves, and built important fortified cities on top of hills. The Etruscan league burgeoned for a while until Etruria was weakened by a series of setbacks in warfare which occurred from the fifth century BC onward until eventually the entire society was swallowed by Rome.

Despite the fact that the Etruscans were the most important pre-Roman civilization of Italy (which left a cultural stamp on almost all Roman institutions) they remain surprisingly enigmatic. Although Greek and Roman authors speculated about the Etruscans, such writings tend to be…fanciful. The Greek historian Herodotus (alternately known as “the father of history” or “the father of lies” wrote that the Etruscans originated from Lydia (which was on the Western coast of Anatolia), but he certainly provides no evidence. Etruscan government was initially based around tribal units but the Etruscan states eventually evolved into theocratic republics–much like the later Roman Republic. The Etruscans worshipped a large pantheon of strange pantheistic gods. The Etruscans produced extremely magnificent tombs which were used by seceding generations of families.

It is through their tombs that we have truly come to know about the real Etruscans. The burial complexes are repositories of art and artifacts which reveal the day-to-day life of the people (well, at least the noble ones who could afford sumptuous tombs). Perhaps, more importantly, the actual Etruscans are also there, albeit in a somewhat deteriorated and passive state. With the advent of advanced genetic knowledge and tests, scientists and anthropologists have been able to conduct mitochondrial DNA studies on Etruscan remains. Such studies suggest that the Etruscans were from…Tuscany, Umbria, and Latium. They were most likely descendents of the Villanovan people—an early Iron Age people of Italy who in turn descended from the Urnfield culture.

This idea tends to conform with what linguists believe concerning the language of the Etruscans—which turns out to be a non-Indo-European isolate with no close language relations. Etruscan was initially an oral language only and it was only after cultural interchange with the Greeks that it acquired a written form (based around a derivation of the Greek alphabet). A few Roman scholars knew Etruscan (among them the emperor Claudius) but knowledge of the language was lost during the early days of the Empire. Today only a handful of inscriptions, epitaphs, and one untranslated book survive. We are left with a people who had unparalleled influence on Rome, yet are only known through inconclusive Greco-Roman accounts and through a tremendous heritage of art and artifacts. These latter are immensely beautiful and precious and form the basis of our knowledge of these mysterious early Italians.

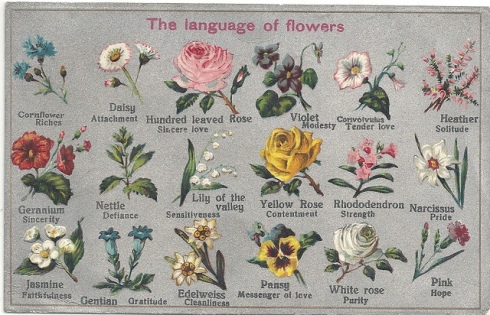

A visit to a museum of fine art with a collection of works older than a century quickly convinces the viewer that flowers have a symbolic language which has long been of paramount importance to human concerns. However, as one walks through rooms of Dutch still life bouquets, pre-Raphaelite garden scenes, and post-modern steel blossoms, one also longs for a symbolic guide. Flowers have long held a cryptographic significance but the idiom varies from culture to culture—even from person to person. The Victorians, who were positively crazy for flowers (but famously bashful in person) tried to standardize the language of flowers in order to make things more clear. They utilized classical poetry and art for certain long-held associations and invented a huge number themselves: the result was the famous “language of flowers”.

Ideally a courting couple would exchange bouquets which included romantic-messages (the concept was possibly invented by horticulturists and the florists’ guild). Daily “talking bouquets” let couples know how each partner was feeling. Awkward suitors pinned their hopes on extravagant floral gifts. As the popular culture of the nineteenth century picked up on the concept, it became part of the literature, theater, and art of the time. Publishing houses sold floriographies—dictionaries of flowers—which can still be read or found online: You can look at a more comprehensive online “floriography” here, but I have isolated some choice examples below:

Heart’s Ease: thought

Hyacinth (yellow): jealousy

Larkspur (pink): fickleness

Nasturtium: Conquest and victory in battle

Mock Orange: Deceit

Orchid (Cattleya): Mature Charm

Peony: Shame; gay life; happy marriage

The experience is somewhat queasy-making. It is hard not to wince at all the inappropriate or offensive things I have said to various young ladies I have esteemed (or, indeed, to my friends–since I like to bring flowers as dinner gifts or thank you presents).

The language of flowers was most en vogue in Western Europe and the United States from 1810 to 1880. However just as it evolved from a long antecedent of flower symbolism it has also cast long shadows—and flowers have played substantial roles as signifiers in movies, television, and popular music up to this day. None-the-less the high formalism and stilted exactitude of the language of flowers has faded into the twilight (thankfully, since goodness knows what the Victorians would have thought of dyed orchids and anthuriums.